Have you ever had a heated argument where the tension was so high the dialogue broke down? Maybe it happened at work with a colleague (or your boss), or with a friend or family member.

Humanitarians working in conflict or violent zones work constantly to overcome these situations. They negotiate with army generals, soldiers at checkpoints or even with families at hospitals who are looking out for their loved ones.

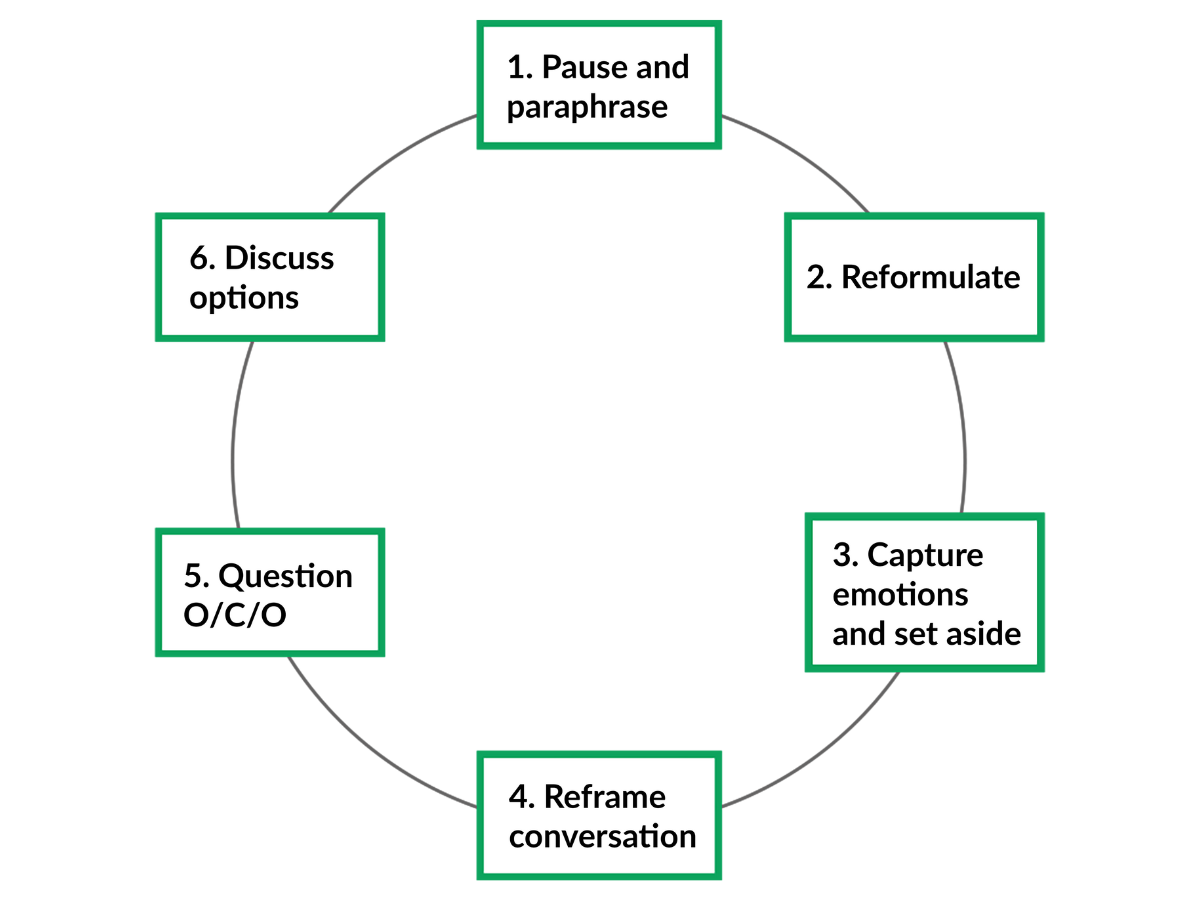

Researchers at the Centre of Competence on Humanitarian Negotiation recommend humanitarian negotiators use these six techniques to help cool down a heated negotiations, ease tension and rebuild dialogue. These techniques are based on a model developed by ADN Group, an agency of professional negotiators based in Paris.

Setting the scene

Imagine you are a nurse working for a humanitarian organisation focused on providing health services. Let’s call that organisation Health for All.

As a nurse, you currently work in a camp for displaced people. For the past few weeks, there has been an outbreak of a viral infection. The virus is highly contagious and children under five are likely to develop deadly complications, but the disease can be prevented by a vaccine.

Your job is to run the camp clinic and vaccinate children against the disease. However, the community living in the camp is really hesitant about getting the vaccine, particularly the people who have been internally displaced.

One day, on your rounds around the camp, you find yourself face to face with the father of a child. He is angry and suspicious about vaccines and claims the government is injecting dangerous chemicals into children to make them sicker; he is refusing any vaccine for his kid. The father claims you’re a government agent and he will not deal with you.

The situation is beginning to escalate. You feel attacked and tell the father to calm down and use a respectful tone with you.

In a split second, the father’s frustration and aggressiveness take over. The relationship is strained, and dialogue has broken down—or is about to.

You feel completely paralised. What do you do?

How do you ease the tension and rebuild the dialogue?

1. Pause the conversation and validate the emotion

First, pause the conversation. Then, acknowledge the emotion the father is feeling without getting caught up in it.

You can say:

- I hear you.

By pausing the conversation (by up to seven seconds), you can begin to disarm the tension and create a space to address the father’s emotions.

When addressing the father’s feelings, try to capture their essence. Be as precise as possible. Keep in mind that anger is usually a blanket emotion for others like frustration, fear, disappointment, or rejection.

You can say:

- I hear that you are concerned/worried for your child’s well-being…

Be careful with using the phrase “I understand.” Depending on the situation, this statement can backfire. Some people could take it the wrong way and point out that you can’t possibly ‘understand’ what they are feeling or going through because you haven’t survived a war or suffered through a famine or lack of medicine.

2. Reformulate the emotion and address the real issue

After pausing and identifying the emotion, reformulate it and try to pinpoint the real issue behind the father’s reaction. Articulate what you see and hear, particularly the context around the emotional reaction.

- Nurse: You are worried because of the vaccine. You think the vaccine will make your child sick. But you are also anxious about your child getting the disease. Am I right?

- Father: Yes, that’s how I feel.

By reformulating the statement about the father’s emotions, you can reduce tension and bring him back into an open dialogue. The anxiety and the volume of the father’s voice may still be high, but that’s okay, don’t hurry to turn these down.

Listening to what is being said and reflecting it back is what allows us to connect with others. This is what allows us to be empathic.

When people are in crisis, the emotional part of the brain takes over and proposing rational solutions at this moment only worsens the tension. The more you try to convince them they are wrong and you’re right, the more the person will fight you.

Instead, try to analyse the behaviour and not react emotionally. Try to avoid putting up a barrier between you and the other person and focus on building the relationship by reframing the conversation. It’s by managing your own emotions that you can influence how others feel.

Once the emotional reaction simmers down and stabilises, you can move forward and present a logical solution.

- Nurse: We need to find ways to address these concerns. Would you agree?

3. Capture the emotion and set it aside

Next, you capture the emotion and set it aside, as if to suspend it. Slowly, this will open the conversation and lead to a potential collaboration.

You could say:

- I can see that you doubt Health For All’s intentions regarding the vaccination. We need to find a way of addressing this. Health For All is a humanitarian medical organisation, and its mission is to ensure access to quality healthcare for children. We operate based on internationally recognised medical standards and guidelines.

4. Reframe the conversation

Now you can reframe the conversation without the emotion, offering the father the opportunity to express his concerns in a rational and pragmatic manner. Give the father the space to express a solution that feels comfortable to him.

For instance:

- Nurse: We are here to serve the medical needs of the people. How can we address your concerns about the health of your child? Can we find ways of looking together at some of the concerns raised?

- Parent: I don’t want to expose my child to any health risk.

- Nurse: We can talk about this together.

5. Ask a series of open and closed questions

Once you’ve created the space for an open dialogue and set the emotion aside, you can help the father identify different solutions. Imagine you are helping him create a scale of possibilities.

The way to do this is by asking a series of open and closed questions.

Open questions refer to the five ‘w’—who, what, where, when and why—and can also include how.

A word of caution: be careful when asking why. If you ask: “Why did you say that?” or “Why do you think so?” the father might perceive it as an accusing question and feel attacked.

By using open questions, you give the father space to expand on how he feels. Be ready for the answers!

- Open question: What if you have a high chance of guarding your son against this bad disease by vaccinating him?

Asking ‘what if’ is a way to get the person to visualise and think about the solution, and what it would look like.

Closed questions refer to questions that can be answered by ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

- Closed question: Do you trust the local nurses?

Keep in mind that the answers to these questions are not yet choices to be negotiated, but rather options to help rationalise the issues from the perspective of the father.

- Open question: What do you think will happen if we don’t vaccinate your son?

Let the father answer the questions out loud. When people hear themselves out loud, they are usually hearing a more reasoned solution for the first time.

The full sequence could look something like this:

- Open questions: What if you have a high chance of guarding your son against this bad disease by allowing him to get vaccinated?

- Closed question: Do you trust the local nurses?

- Open question: What do you think will happen if we don’t vaccinate your son?

After asking a series of open and closed questions, you can ask a question to frame the father’s answer such as:

- Nurse: You mentioned earlier that you’re concerned about the vaccination, but you also said that you are more concerned about the disease. What are you most worried about?

The father will likely answer that he is worried about the disease that can kill the child.

As a medical worker, it’s preferable to have a conversation rather than offer or insist that option A is better than option B. By having an open dialogue, it can help encourage the father to come up with the desired answer. This way, he is less emotional and he’ll be more open to a shared solution.

6. Set the terms of the conversation around one or several of the discussed options

As a final step, you can reset the terms of the conversation around the most amenable aspects of the suggested options so the dialogue can move forward on a more rational basis.

At the end, you can try to summarise the exchange by saying:

- So, you came in, you were worried about the vaccination and the disease. I appreciate your worries. Know that I’ve heard how concerned you are. I have dealt with many parents who had the same worries and every one of them have vaccinated their kids and have come back to see us saying that they were glad to make the choice to vaccinate. You correctly evaluated the risks; you did not want to pose any threat to your child. Now you realise that the disease can be more threatening than the vaccine. You choose vaccination knowing that you care for your child; I care for your child, too. I will be here tomorrow, the next day and if a slightest thing goes wrong with your child, I’ll be here to help. Can I tell you more about the vaccination?

In the end, you can provide a logical answer, reassuring the father that you will be there in case anything happens. This way, you are defining a common objective and a shared responsibility. The father wants what is the best for your child, so do you, and you are in this together.

👉Interested in more tools to support your humanitarian negotiations?

- Check out the CCHN Field Manual on Frontline Humanitarian Negotiation, or

- Join one of our entry-level workshops and get instant access to our community of humanitarian negotiators!