The convoy has been waiting at a remote checkpoint for hours. The radio crackles with static, then falls silent; an uneasy quiet that feels almost intentional.

Ahead, armed men argue in a language none of us understands.

We watch them closely: their tense movements, fingers twitching near triggers, eyes red from exhaustion or something darker. Their words make no sense to us, but their unease is clear.

A hundred bad outcomes flash through my mind: a misunderstanding, a demand we can’t meet, a warning shot, or worse. Out here, there’s no backup, no quick escape. No one to call for help.

As the men blocking the road grow more agitated, I glance at the trucks behind us, each loaded with medical supplies desperately needed at a hospital already out of antibiotics.

The radio crackles again. After a tense exchange and a long pause, the commander finally agrees to talk. This negotiation will decide if our supplies reach those in need—or if we’ll have to turn back. For us, it might also mean the difference between safety and danger.

Every humanitarian worker negotiates.

Whether you’re speaking with government officials about visa restrictions, armed groups about safe passage, or community leaders about aid distribution, you’re navigating competing interests to secure humanitarian access.

The question isn’t whether you negotiate – it’s whether you do it effectively.

This blog introduces you to the essential skills that transform challenging conversations into successful humanitarian outcomes. More importantly, it shows you how these skills work in real situations, through case studies from practitioners who’ve navigated some of the world’s most complex crises.

What makes humanitarian negotiation different?

Before we explore specific skills, it’s crucial to understand what sets humanitarian negotiation apart.

According to the CCHN Field Manual, humanitarian negotiation is any conversation you have with someone to:

- Establish and maintain your organisation’s presence in a crisis environment;

- Ensure access to people affected by crises;

- Deliver humanitarian assistance and carry out protection activities.

Unlike commercial negotiations, where profit drives decisions, humanitarian negotiations balance two critical components:

- The relational component: Building and maintaining long-term relationships with counterparts, often in contexts where you’ll need to negotiate repeatedly over months or years.

- The transactional component: Achieving specific, immediate outcomes, like gaining access to a village, permission to distribute aid, and guarantees of safety for your team.

Most importantly, humanitarian negotiations operate within strict boundaries. The four humanitarian principles of humanity, impartiality, neutrality, and independence frame every conversation, every compromise, and every decision you make.

CASE STUDY

I was working as a humanitarian protecting civilians in a region where years of war had left villages isolated, and fighting was still active. Farmers had blockaded the roads, armed groups controlled the checkpoints, and people were dying at home because ambulances could not reach the hospital. I knew I had to negotiate for the ambulances to be let through, but I was uncertain how the protest leaders or armed commanders would respond.

I began by meeting the protest leaders beside the barrier. They didn’t command the armed men, but they could influence the crowd. I explained that my only goal was to get the sick and injured to care. By focusing on our shared concern for human life, we agreed to a first test passage: a quick search, no filming, no flags, lights on, siren low. Seeing it succeed gave me confidence.

Next, I approached the armed commander. I requested three guarantees: no fighters or detainees in ambulances, no arrests or tailing during transfers, and no propaganda using the medical lane. In return, I offered strict transparency measures: logs of plates and times, fixed hours, driver IDs, coloured passes, and a pause-and-restart plan if shots were fired.

That night, the passage opened. A child with asthma and a man with a broken leg reached the hospital safely. Even as fighting continued, I saw that by centring humanity in these conversations, negotiation saved lives.

This principled approach creates unique challenges. You can’t simply “win” a negotiation or maximise your position at your counterpart’s expense. You must find solutions that respect humanitarian principles while meeting the urgent needs of affected populations.

Now, let’s explore the essential skills that make this possible.

Phase 1: Before the conversation begins

The power of preparation

The most critical negotiation work happens before you sit down with your counterpart.

Humanitarian contexts are politically charged, full of misinformation, and constantly shifting. Walking into a negotiation without solid preparation is like performing surgery without an X-ray.

Essential skills:

1. Context analysis: Gather reliable data about the situation.

- What’s happening on the ground?

- Who controls different areas?

- How many people are affected?

- What are the political dynamics?

The more you understand the environment, the better you can anticipate challenges and identify opportunities.

2. Stakeholder mapping: Your immediate counterpart—the person across the table—rarely acts alone. They answer to commanders, community leaders, political figures, or family networks.

Building a stakeholder map helps you visualise these relationships and identify who can influence your counterpart’s decisions. Think of stakeholder mapping as creating a power constellation.

- Who are the “stars”?

- Who orbits whom?

- Where can you apply gentle pressure to shift the entire system?

3. Team assembly: Who should participate in the negotiation?

Consider not just seniority but also gender, nationality, language skills, and personal relationships with counterparts. The right team composition can open doors that remain closed to individual negotiators.

CASE STUDY

I was assigned to work as a water engineer on a new mission visiting detention centres.

For over 20 years, international colleagues had advocated for improving the basic conditions of detainees, to no avail. As a local woman, I was uncertain of how the prison authorities would respond to me, so I decided to use the CCHN stakeholder mapping tool. I discovered that prison officers were hesitant to show their hierarchy that they cared about improving detention conditions and didn’t fully trust humanitarians.

Recognising the need for trusted allies, I enlisted government engineers familiar with both worlds to join me during facility inspections. Together, we documented needs so that when recommendations to improve conditions reached the prison authorities, they came from respected voices rather than from an outsider.

Through strategic negotiation, local alliances, and careful application of the stakeholder mapping tool, I transformed two decades of resistance into meaningful change.

Practical takeaway: Use the Naivasha Grid to systematically prepare your negotiation strategy. This framework, developed from real-life negotiation practices, helps you analyse context, identify stakeholders, and develop tactical plans.

Phase 2: Opening the conversation and building rapport

Starting on common ground

You’ve done your homework. Now comes the moment when you face your counterpart. How you begin determines everything that follows.

In tense environments, it’s tempting to immediately address disagreements: the blocked checkpoint, the denied permits, the detained staff member. Resist this urge.

The opening strategy

Start by establishing what you both agree on.

This might be factual information (the number of people in need, the security situation), shared concerns (community welfare, regional stability), or mutual interests (public health, preventing disease outbreaks).

Starting a negotiation on common ground creates psychological safety. It signals that despite your differences, you share some understanding of reality. Only after establishing this foundation should you address areas of disagreement.

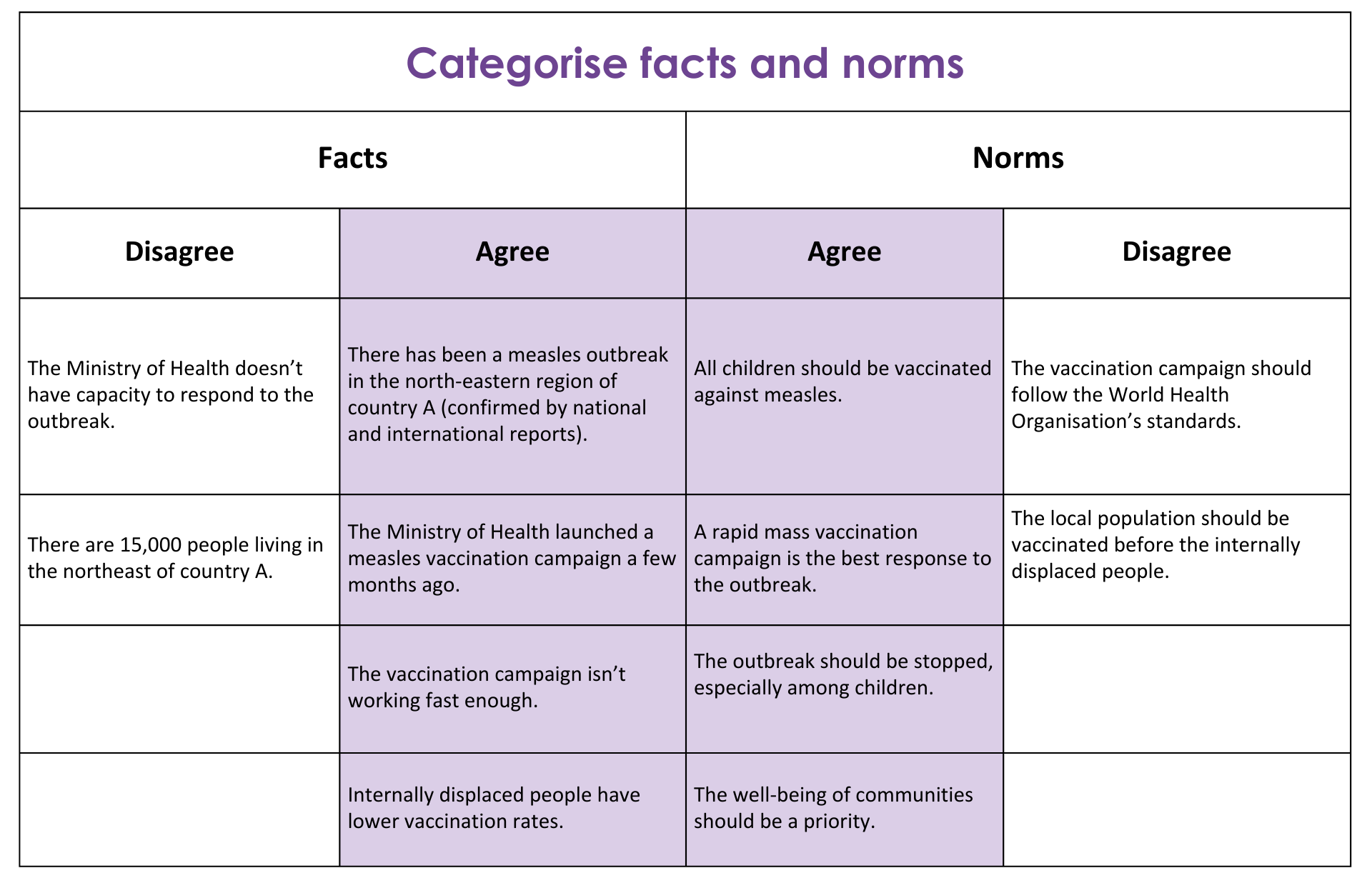

Sort information into agreed facts and norms, and disagreed facts and norms. For example, you and your counterpart can agree that there is a measles outbreak (agreed fact) and that all children should be vaccinated (agreed norm). However, you might disagree about how many people there are (a disputed fact) and what health standards should be followed (a disputed norm). Focus on the agreed facts and norms to build your opening argument.

Active listening

The most underrated negotiation skill isn’t speaking eloquently; it’s listening deeply. When your counterpart talks, they’re giving you invaluable information about their priorities, constraints, fears, and motivations. Listen not just to their words but to what drives those words.

Ask yourself:

- What values underpin their position?

- What pressures are they facing from their own stakeholders?

- What are they really asking for beneath their stated demands?

Cultural competence

Humanitarian negotiations span dozens of cultures, each with different communication styles, decision-making processes, and concepts of trust. What signals respect in one context might offend in another. What builds trust quickly in one culture might seem suspiciously hasty in another.

Cultural competence doesn’t mean memorising lists of “dos and don’ts.” It means approaching each context with humility, observing carefully, and adapting your approach based on what you learn.

CASE STUDY

My first mission was in Iraq. I was tasked with providing assistance to people residing in a camp.

As my team and I arrived at the camp, we were met by a protest at the entrance. They told us that fuel tankers had not been allowed into the camp for the past few weeks.

The residents were desperate. They didn’t have drinkable water or fuel to power the air conditioning in their living containers. Children started getting sick, and the heat was reaching unbearable highs.

I decided to use the “negotiation iceberg” tool, a method that helps analyse the real reasons and motives behind someone’s actions.

My team and I decided to talk with the camp authorities to understand what was happening. After some conversations, we understood they didn’t want fuel tankers entering the camp because they feared they might carry explosives. They also suspected the camp residents had enough fuel but were secretly hiding large reserves.

We decided to search the camp but couldn’t find any secret reserves. After reporting our findings to the authorities, we asked if they would allow just one tanker to enter, with our escort.

It seemed we had touched upon the real issue behind their hesitation. We successfully negotiated for the fuel tanker to enter the camp.

I’ve learned that getting to know your counterpart as well as you can unlock even the most stubborn negotiation. I now frequently use the “iceberg” tool with my team. It means that we go into the negotiation not completely blind or unprepared, but with possible scenarios for how it could go in the best-case and worst-case scenarios.

Phase 3: Navigating complexity

Understanding the iceberg

Your counterpart tells you they can’t allow your convoy to proceed. That’s their position or the demand they’re making. But positions are just the tip of the iceberg.

Beneath every position lies reasoning, which is the logical argument supporting their stance. “The security situation is too dangerous.” “We can’t guarantee your safety.” “Other organisations caused problems.”

Deeper still are values: the fundamental beliefs and priorities driving their reasoning. Security, sovereignty, religious principles, family honour, political loyalty, or community welfare.

Building common ground requires diving beneath positions to understand reasoning and values. When you grasp what truly motivates your counterpart, you can craft solutions that address their underlying concerns rather than just battling over surface-level demands.

The creative exercise: Map your own iceberg—your position, reasoning, and values—alongside your counterpart’s. Where do the values align? Where might your reasoning support their concerns? This shared space is where negotiated agreements live.

Setting clear boundaries

Here’s a hard truth: not every negotiation should succeed. Some proposed “agreements” would violate humanitarian principles, endanger affected communities, or compromise your organisation’s integrity.

Setting clear boundaries means understanding three critical levels:

- Ideal outcomes are the best possible results for both parties. These are ambitious but realistic goals that would fully meet humanitarian needs while satisfying your counterpart’s requirements.

- Bottom lines are the minimum acceptable thresholds at which benefits still outweigh costs and risks. Cross this line, and the negotiation is no longer worth pursuing.

- Red lines are non-negotiable limits based on humanitarian principles and organisational policy. These you cannot cross under any circumstances, regardless of pressure or incentives.

The most beneficial agreements typically fall within both parties’ bottom lines while respecting all red lines. This creates what we call the “zone of possible agreement.” In other words, it’s the space where compromise serves everyone’s core interests.

CASE STUDY

I was supporting a nutrition education project in central Mali, where years of conflict and armed group control had disrupted community life and access to food, and left many children malnourished. Our goal was to help families improve infant feeding and hygiene through an educational programme. But the first session in a rural village quickly turned into a crisis: armed actors arrived, stopped the session, and punished the village chief for allowing men and women to gather. Fear spread, and all activities were suspended.

To resume the program safely, I turned to the CCHN tool on red lines and bottom lines. I identified the armed group’s red line (they would never accept mixed-gender sessions) and our ideal outcome (children should not continue to suffer from malnutrition). With these boundaries clear, we could explore tactical compromises that protected children’s well-being while respecting the armed group’s constraints.

Community elders, mothers, and teachers led the dialogue. We proposed separate sessions: women at the health centre with the midwife, men at the school with a male facilitator. By framing the project around shared moral values of children’s health and family care, we built trust and opened space for negotiation.

The sessions resumed safely, participation grew, and children gained access to essential nutrition knowledge. By clearly defining red lines and bottom lines, we upheld humanitarian principles while adapting to local constraints, showing how principled negotiation can save lives even in highly constrained environments.

Managing pressure

Humanitarian negotiations aren’t academic exercises. They’re emotionally intense, physically exhausting, and ethically complex. You might be:

- Negotiating while people die waiting for aid

- Facing counterparts who threaten or intimidate

- Managing competing demands from headquarters, donors, and communities

- Carrying responsibility for your team’s safety

Your ability to think clearly and act strategically depends on managing stress in real-time. When adrenaline floods your system during a tense negotiation, your prefrontal cortex, the part of your brain responsible for complex thinking, can go offline.

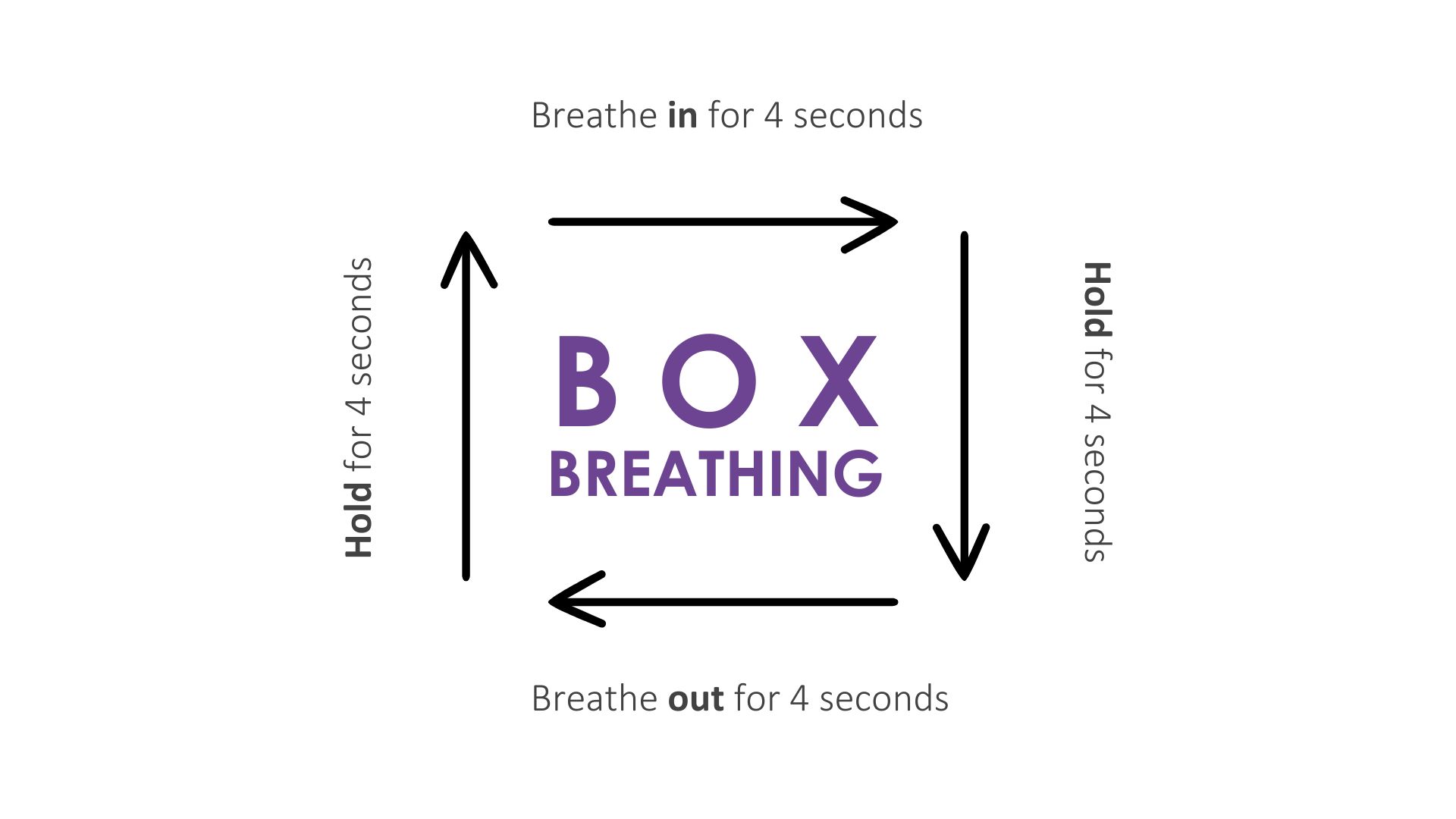

Practice the box breathing technique: Inhale for four counts, hold for four, exhale for four, hold for four.

This simple exercise activates your parasympathetic nervous system, helping you regain emotional control and cognitive clarity.

But pressure management isn’t just an individual skill. Organisations must create systems that support negotiators: realistic timeframes, psychological support, team debriefs, and permission to walk away from dangerous situations.

Phase 4: Building for the long term

Trust as infrastructure

In protracted crises, you’ll negotiate with the same counterparts repeatedly. Today’s checkpoint conversation becomes next month’s detention incident, which becomes next year’s access discussion for a new program.

This reality makes trust your most valuable asset—and your most vulnerable one.

Building trust in humanitarian negotiations rests on three pillars:

- Predictability

Do what you say you’ll do, when you say you’ll do it. If circumstances change and you can’t deliver, communicate early and honestly. Predictability doesn’t mean inflexibility; it means reliability within your commitments.

- Clear communication

Ambiguity breeds suspicion. Be direct about what you can and cannot do, what you’re asking for, and what you’re offering. Avoid jargon, use concrete examples, and confirm mutual understanding.

- Strategic flexibility

While principles remain firm, tactics can adapt. Show willingness to adjust timelines, modify approaches, or consider alternative solutions that achieve the same goals. Flexibility signals respect for your counterpart’s constraints.

CASE STUDY

When Bashar al-Assad was the president of Syria, my organisation was active in the country’s northwest. During that period, the city of Idlib, where we operated, was under the control of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), an armed opposition group.

To carry out our humanitarian work, we had to build a relationship with HTS. At the time, it lacked the resources, military strength, and financial capabilities it possesses today.

Now that HTS has begun to govern the country, its scope of operations has expanded significantly. However, despite this regime change, thanks to the relationship my organisation had established with HTS five years before the group’s rise to power, our operations have continued without interruption.

When dealing with non-state armed groups, keep in mind that their status can change and that they might become the ruling authority. Humanitarian contexts are inherently volatile, and the quality of your relationship with your counterparts could make a vital difference in the future.

Trust isn’t a soft sentiment; it’s an operational infrastructure. When a crisis strikes, you’ll negotiate based on the relational foundation you’ve built. Strong trust enables faster agreements, better information sharing, and more sustainable solutions.

When negotiations get difficult

Facing reality head-on

Not every negotiation succeeds. Sometimes, counterparts act in bad faith. Sometimes political dynamics shift beyond your control. Sometimes the gap between positions proves unbridgeable.

Here’s what experienced humanitarian negotiators know:

Power imbalances are real: You’ll often negotiate from a position of relative weakness—with armed groups who control territory, governments who control visas, or commanders who control access.

This doesn’t make negotiation impossible; it makes strategy essential.

When facing more powerful counterparts:

- Leverage your unique value (humanitarian expertise, international attention, community relationships)

- Build coalitions with other stakeholders who share your interests

- Focus on mutual benefits rather than competing demands

- Document everything to create accountability

Failed negotiations teach

The negotiation that didn’t work often teaches more than the one that succeeded smoothly. After difficult negotiations, conduct thorough debriefs: What assumptions proved wrong? What signals did we miss? What could we do differently?

Create a culture where teams can discuss failures openly without blame. These lessons become institutional knowledge that helps the next negotiator avoid the same pitfalls.

Ethical dilemmas are inevitable

You’ll face situations where all options feel wrong, where saying yes compromises principles and saying no abandons people in need. These dilemmas don’t have clean answers. They require:

- Consultation with colleagues, supervisors, and ethics advisors

- Clear documentation of decision-making rationale

- Honest acknowledgement of trade-offs

- Willingness to escalate to senior leadership when needed

CASE STUDY

I was working as a nurse in a camp. One day, on my rounds around the camp, I found myself face-to-face with the father of a child living there. He was angry and suspicious about our vaccine campaign, claiming the government was injecting dangerous chemicals into children to make them sick, so he refused to vaccinate his child. The father also claimed I was a government agent and that he would not deal with me.

The situation began to escalate. I felt attacked and told the father to calm down and use a respectful tone with me. In a split second, his frustration and aggression took over. The conversation became strained, and the dialogue had broken down—or was about to.

I felt completely paralysed, but remembered the de-escalation protocol.

The most urgent step was to validate the father’s emotions. I let him know I heard his frustration and concern for his child’s well-being. Then, I mirrored his words, repeating what he had expressed: he was worried the vaccine would make his child sick, and at the same time, he was anxious his child would get the disease that was spreading in the camp. I acknowledged his doubt about my organisation’s mission and began addressing it by explaining how we worked. This allowed me to reframe the conversation and focus on how we could address the father’s concerns together. After asking what an acceptable solution would be, the father settled down and decided to vaccinate his child after all.

Remember...

Negotiation isn’t a talent you’re born with; it’s a professional competence you develop through learning, practice, and reflection. Every experienced negotiator you admire started exactly where you are now, facing the same uncertainties and questions.

The humanitarian workers who negotiate most effectively aren’t those who never feel nervous or uncertain. They’re those who’ve built skills systematically, learned from their mistakes, and continued developing throughout their careers.

Your negotiation journey doesn’t require perfection. It requires commitment to learning, practising, respecting humanitarian principles, and serving the people who depend on the agreements you reach.

The next time you approach that checkpoint, that government office, or that community meeting, you’ll do so with sharper tools, clearer strategies, and the support of thousands of practitioners who understand exactly what you’re facing.

The conversation—the negotiation—that could make a difference starts with the skills you’re building today.