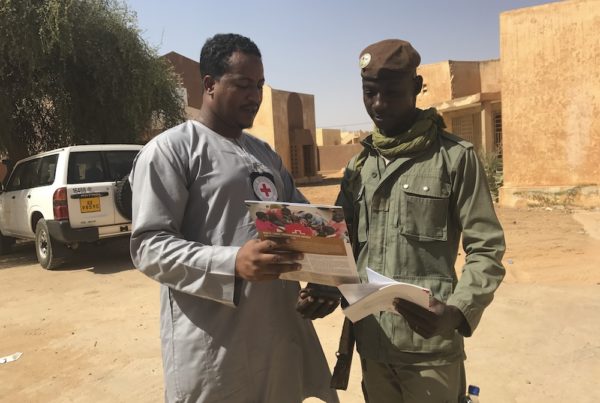

As a humanitarian professional, it’s fundamental to be prepared to negotiate.

One way to be ready is to develop your soft skills.

For instance, by recognising your counterpart’s emotions and what they mean.

Understanding what emotions are, why people use them, what they mean and which emotions you can use in a strategic way will help be a better humanitarian negotiator.

Who better to help us dig into the world of emotions than Dr Smadar Cohen Chen, Associate Professor of Organisational Psychology in the Management Department at the University of Sussex Business School.

Dr Cohen Chen researches the link between psychology and real-world questions of people and group dynamics, focusing on emotions, emotion regulation and emotional expressions in intergroup and interpersonal conflict and negotiations.

Let’s understand the power of emotions, their expression and how you can use them strategically in your negotiations.

The power of emotions

First, what are emotions exactly?

According to Dr Cohen Chen, they are “flexible response sequences that happen or are elicited when someone believes a situation can offer important challenges or opportunities.”

What people feel after a certain event will be based on personal experiences, personality traits, the context, and more – so they may vary greatly based on who we are. Emotions will also lead to certain attitudes and behavioural tendencies. For instance, if someone gets angry, they might feel the impulse to get violent with the other person, while others may have a more restrained reaction.

Why are emotions so powerful?

Research shows that the more we ignore our emotions or don’t understand them, the more they control our behaviour.

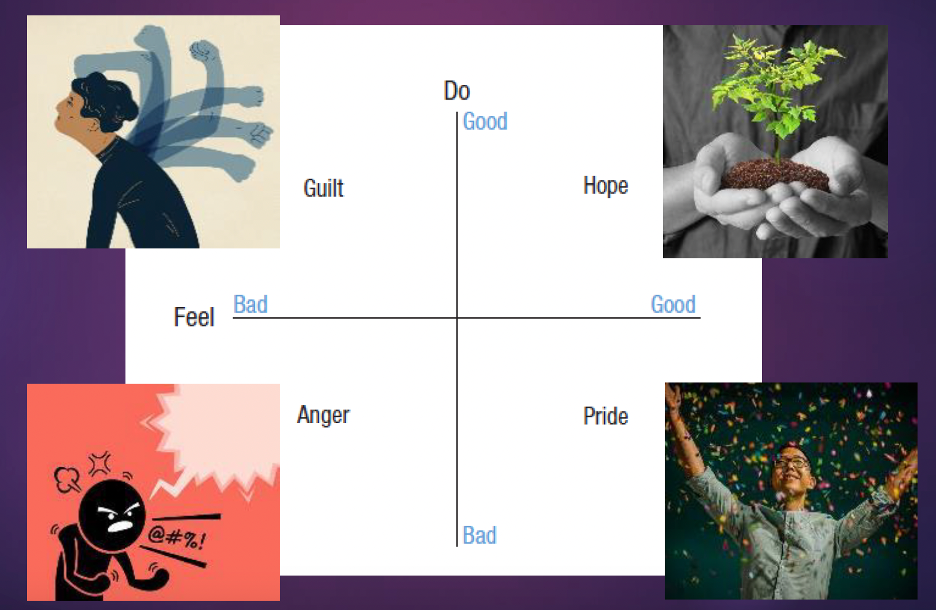

There are positive and negative emotions, and they are defined really differently. Positive emotions make you feel good and make you do good. Conversely, negative emotions make you feel bad and make you do bad.

Source: Smadar Cohen Chen

Let’s look at 10 of them, and how each may impact behaviour during a negotiation.

Anger is characterised by short-term aggressive responses but long-term conciliation. It can also lead to take risks and even make more concessions, because it is associated with a feeling of power. Anger can be functional in some situations: it is based on the idea that a person or a group wronged you, but they are able to change – this logic can lead to conciliation.

Fear induces cognitive freezing, meaning someone will loses their train of thought or forget what they are doing. It makes people focus on threatening information and prevents them from being open to new ideas. Instead, they will focus on information that confirms their fear even more.

People who feel contempt will likely reject and socially exclude others. There are little to no functional outcomes for this emotion, so it won’t help you achieve something during a negotiation.

Guilt is an emotion that makes us feel bad but makes us do good. People who feel guilty tend to take responsibility, apologise and make reparations for past wrongdoing.

Empathy is linked to cooperation. It is not necessarily a good emotion to feel, because we become attuned to other people’s emotions. When we feel empathy, it can hurt to see someone in pain or suffering. It means we want this feeling to go away, and we become more motivated to cooperate.

Pride makes us feel good and empowered but often leads to negative consequences. It is associated with increased aggressiveness. It can result in behaviours that are not functional for conflict resolution or successful negotiations.

Hope makes us feel good and do good things as well. It prompts us to make concessions more easily in conflict and to become more supportive when aiming to reach an agreement. When people feel hopeful, they tend to search for information that supports their conflict resolution ideas.

People who feel disgust may be inclined to judge actions more severely. It is more likely that people experiencing disgust will consider a certain behaviour as immoral.

Hatred and humiliation may create thoughts of annihilation and destruction of the other side, and of extreme aggression and support for aggression. These emotions are almost never functional to a relationship.

Overall, positive emotions – meaning emotions that are pleasant to us – will lead to more pro-social behaviour like collaboration, engagement, positive relationships and more communication. Focus on this kind of emotions to achieve a successful negotiation. Negative ones on the contrary make it harder to build relationships, which is an obstacle to your counterpart collaborating.

We can go even deeper in analysing how emotions can be regulated to our advantage. Let’s have a look at that.

Expressing emotions: will it help me cooperate?

Regulating emotions is the process of influencing what we are feeling, when we feel it, and how we experience and express it.

One important concept is emotional expressions. They give the other side information about what people are feeling, what their intentions are, and what is important to them.

Source: Smadar Cohen Chen

Emotional expressions include facial verbal or written expressions. They will all convey a specific emotion.

These expressions change based on the relationship you have with the person you are addressing.

In the case of a cooperative relationship, we often witness an “emotional contagion”: it means that if you feel a certain emotion, the counterpart in front of you may start feeling the same.

But in a competitive relationship, it’s more likely that people will be learning, studying, and testing your emotional expressions. It means people will think whatever is good for you is bad for them. They will therefore feel the opposite of you. For instance, if something is making you happy, they may think the circumstances have bad repercussions for them.

People will also perceive your emotions as strategic. For example, if you look angry, they will see that their words or actions are affecting you. If you seem fearful, they will know that their behaviour is threatening; they may want to “push” even harder.

Let’s look at a few specific expressions.

Anger expressions can induce concessions in negotiations, but they can also lead to retaliation in the long term. So, when someone shows angry expressions, the other side will try to get back to them and retaliate in the long term if they have the chance.

Sadness expressions can induce cooperation, but they may also be interpreted as weakness. If you appear sad when negotiating, the other side might feel bad for you and make concessions. But they could also consider you as weak and try to take advantage of the situation.

Hope expressions increase concessions and acceptance of agreements. However, they are less likely to affect people who are politically conservative in the context of a conflict.

One thing to keep in mind is that emotional expressions can be a double-edged sword, leading to positive as well as negative outcomes. It means you should use them wisely.

Should I just show indifference instead?

The short answer? No.

Indifference is an ‘anti-emotion’ – in other words the void of an emotion.

If you show indifference, you are telling your counterpart that you don’t care about the situation. Indifference reduces expected collaboration.

If someone was really indifferent, they would not even come to the negotiation table. On the other hand, they’re talking to you: there must be something they plan to achieve.

Watch Dr Cohen Chen’s session where she explains the theory behind indifference.

Remember: emotions are a strong instrument that you can strategically use in combination with the CCHN negotiation tools when planning for and carrying out a negotiation.

Let’s strategise: which emotions should I use?

We have seen that showing emotions may result in outcomes which are opposite to one another.

Expressing anger or empathy can be helpful in a negotiation context, helping you create a connection and lead to action. Feeling contempt or hatred, on the other hand, may be detrimental in the creation of a functional relationship with your counterpart.

Think about which emotions:

- You want to experience.

- You want others to experience.

- Others would want to experience.

Remember:

- The different roles of emotions.

- How they can be either helpful or harmful to your negotiation.

- The implicit messages emotions convey.

- To express emotions in a functional way in negotiations.

Being aware of the power of emotions is a soft skill that adds a lot of value to negotiations.

To improve the work of your negotiation team and to reach the people you are helping as a humanitarian, keep in mind the value of emotions and what they can lead to.