Negotiating is all about finding a compromise. To do so, you need to weigh the risks against the benefits of your actions.

In other words, evaluating how far is ‘too far’ is important when finding an agreeable solution.

First, you need to understand your boundaries and your counterpart’s. Then, you can find a middle ground between the two.

Keep reading to learn how to establish your negotiation red lines, conduct a risk-benefit analysis across different negotiation scenarios, and reach an acceptable agreement for all that respects humanitarian principles.

“Negotiation: The subtle art of finding a compromise that makes everyone equally unhappy.”

– Anonymous author

The art of finding mutual benefits

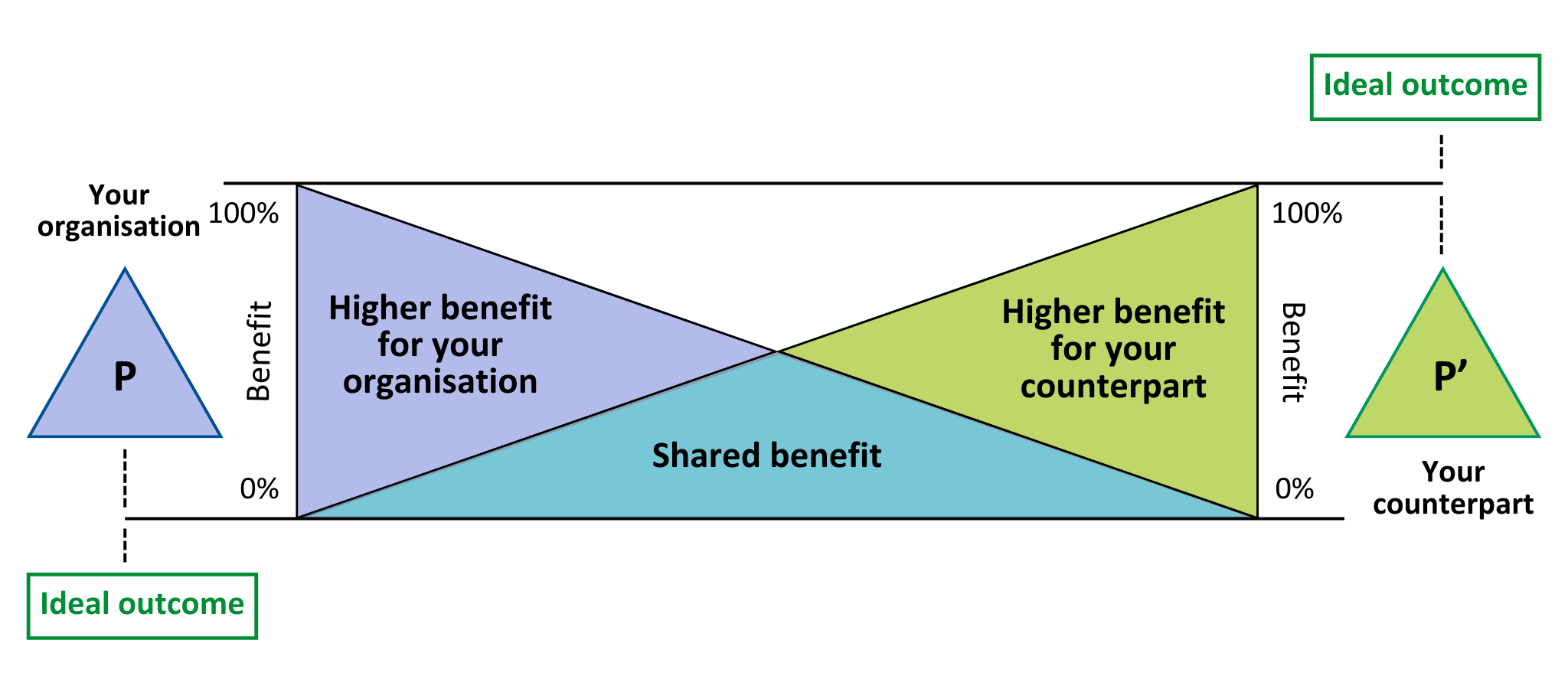

A successful negotiation requires finding a solution that benefits both parties.

When you reach a compromise that creates value for both you and your counterpart, you ensure a more acceptable solution and, therefore, a more sustainable humanitarian intervention.

For you, a beneficial agreement could mean a greater impact on the local population and better security.

For your counterpart, it could support their economic or political interests, such as gaining legitimacy in the eyes of their hierarchy or constituency.

Before you can identify what creates value for both parties, you need to understand your negotiation boundaries. Without clear limits, you risk making compromises that undermine your mission or principles.

Let’s explore how to establish these boundaries first, then we’ll examine how to navigate toward mutually beneficial outcomes.

Know your boundaries: red lines vs. bottom lines

With that in mind, it’s time to understand where your boundaries lie.

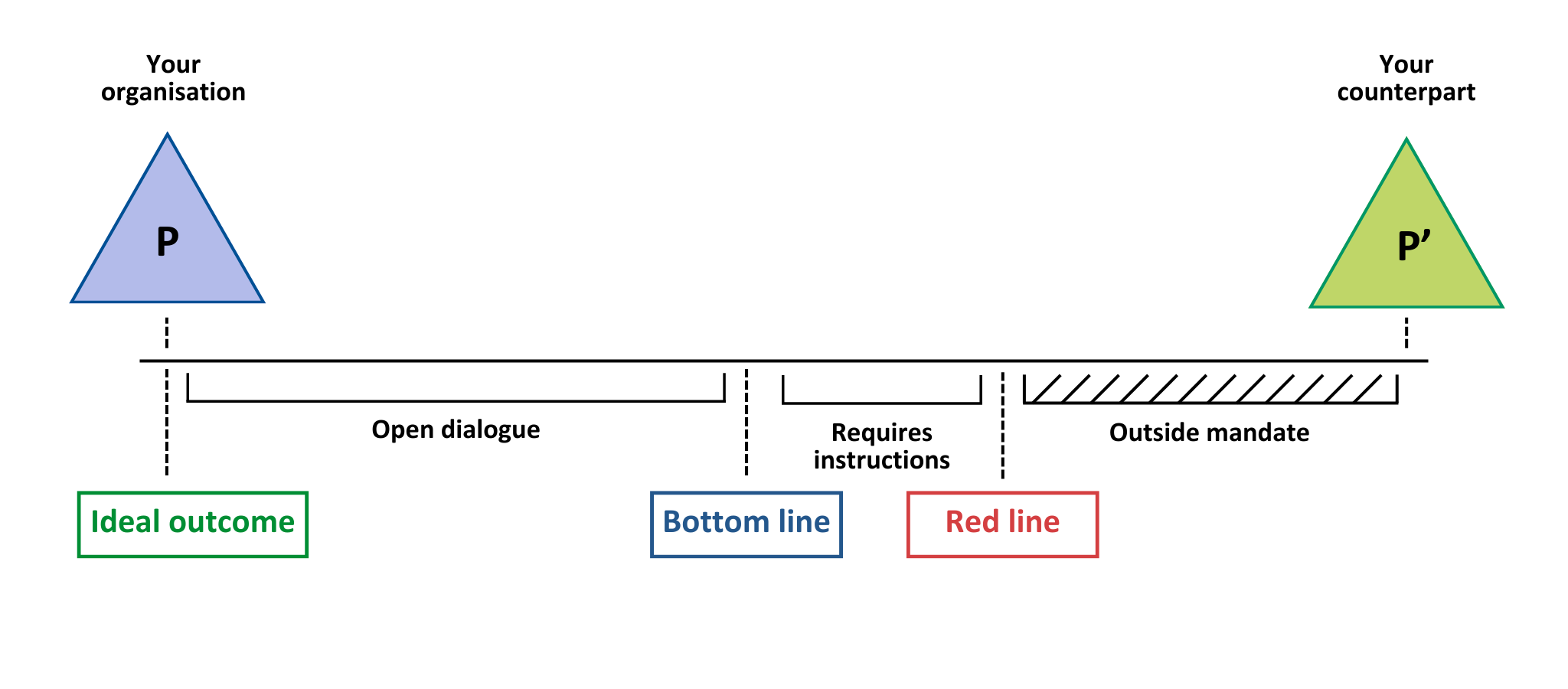

According to the CCHN Field Manual, you can define two kinds of limits to your humanitarian operation:

- Red lines: These are the non-negotiable limits set by your organisation’s mandate. They are based on laws, policies, humanitarian principles and ethical considerations. Crossing a red line can have severe legal and reputational consequences.

- Bottom lines are tactical tools: you define them strategically based on your negotiation objectives. Unlike red lines, they are not fixed; they can change as your objectives change. They represent the threshold at which risks start to outweigh the benefits. Bottom lines offer some flexibility because you can use them to manage the conversation and avoid deals that could jeopardise your organisation’s integrity or operations.

Now that you have the foundation, it’s time to find the right level of compromise.

How far is ‘too far’?

Start with your ideal outcome. Imagine what it would look like if your organisation achieved its goals with minimal compromise.

☝️ Keep in mind, this is a mental exercise. Your ideal outcome will always be unrealistic since it doesn’t consider your counterpart’s interests and motives and does not involve any shared benefit.

Starting with your ideal outcome isn’t naive; it’s strategic. By establishing this anchor point, you create a reference frame that helps you measure each subsequent compromise against your goals. This prevents ‘compromise creep,’ where small concessions accumulate into major departures from your mission.

Then, establish your red lines. To identify your red lines, ask yourself:

-

What actions would violate our mandate or charter?

-

What compromises would expose us to legal liability?

-

What concessions would irreparably damage our reputation or ability to operate?

Document these clearly with your team before negotiations begin. Red lines aren’t decided in the heat of negotiation; they’re established through careful institutional reflection.

Then, establish your bottom lines:

-

Start with your ideal outcome and list progressively less favourable scenarios.

-

For each scenario, quantify the risks for your team and your organisation.

-

Calculate the potential humanitarian impact (people reached, needs addressed).

-

Identify the point where risks equal or exceed benefits: that’s your initial bottom line.

-

Prepare clear criteria for when you’ll pause negotiations to consult with your hierarchy to validate or adjust this threshold.

Watch for these warning signs that you’re approaching or crossing your bottom line:

-

Your counterpart keeps requesting ‘just one more small concession.’

-

You’re rationalising decisions you’d normally reject.

-

Team members express serious concerns about the direction.

-

The compromise would set a precedent that weakens future negotiations.

-

You’re hesitant to document the agreement in writing.

When you notice these signs, it’s time to pause and reassess.

Imagine you are negotiating access to a camp hosting internally displaced people.

- Ideal outcome: Full access to the camp with no military presence.

- First compromise: Full access to the camp with limited military presence.

- Second compromise (bottom line): Full access to the camp with military monitoring.

- Third compromise (red line): Limited access to the camp with military escort and beneficiary lists.

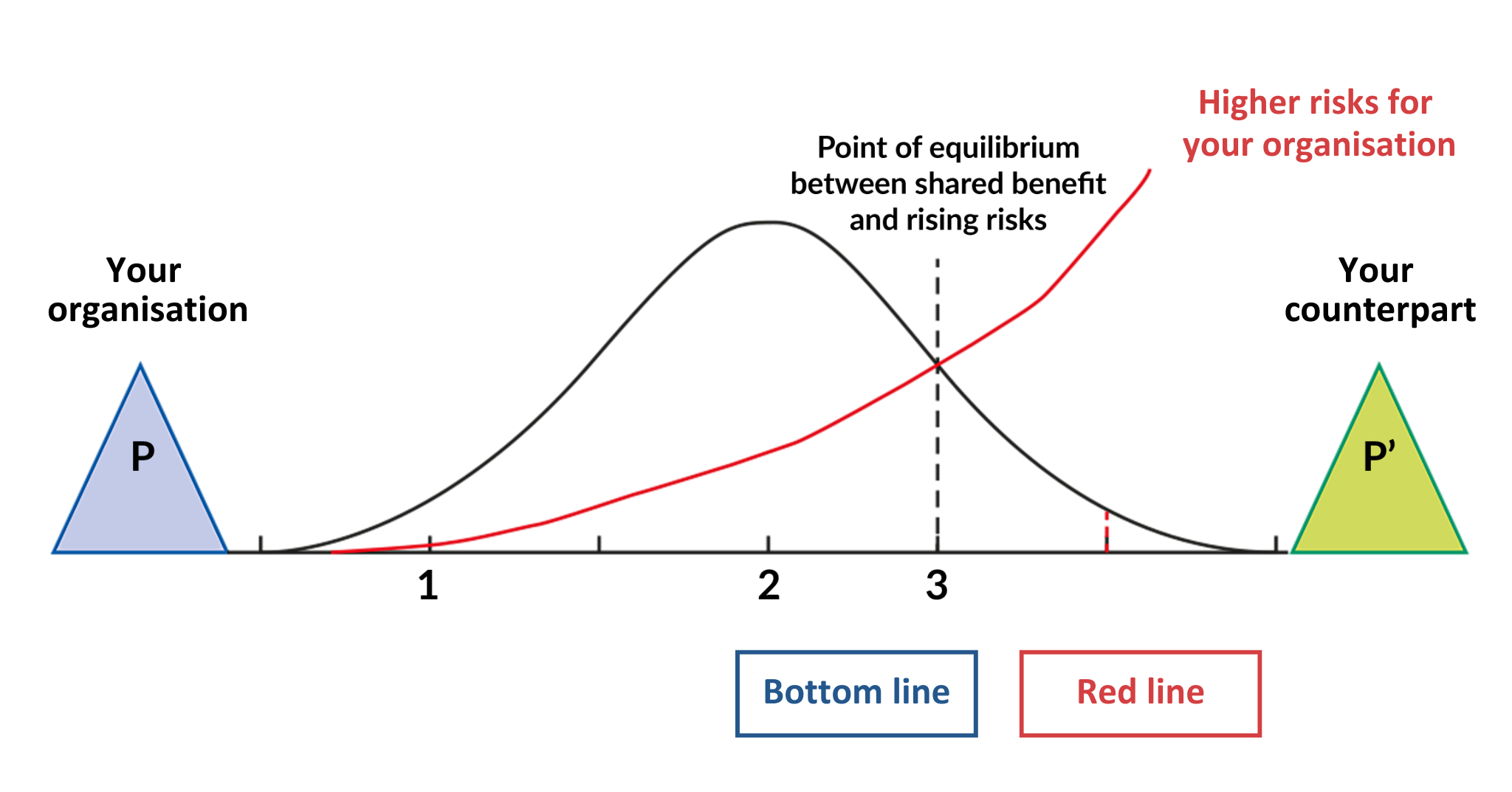

Each compromise brings the negotiation closer to a realistic agreement, but also increases the risks and decreases the benefits for your organisation.

Assessing risks

Compromises come with costs, and it’s vital to evaluate the rising risks to your organisation. Sources of risks include:

- Humanitarian principles

- Staff security

- Protection of affected populations

- Legal norms (e.g. counter-terrorism laws)

- Operational efficiency

- Reputational risks

Let’s return to our IDP camp example. In moving from full access with no military presence (ideal) to limited access with military escort and shared beneficiary lists (red line), which specific risks increased?

Perhaps access improved, but staff security and protection of the affected populations worsened.

By systematically evaluating each compromise against all six risk categories, you can identify deal-breakers before you reach the negotiation table. Use this information strategically to pause negotiations before you agree to risky compromises.

Shared space for agreement

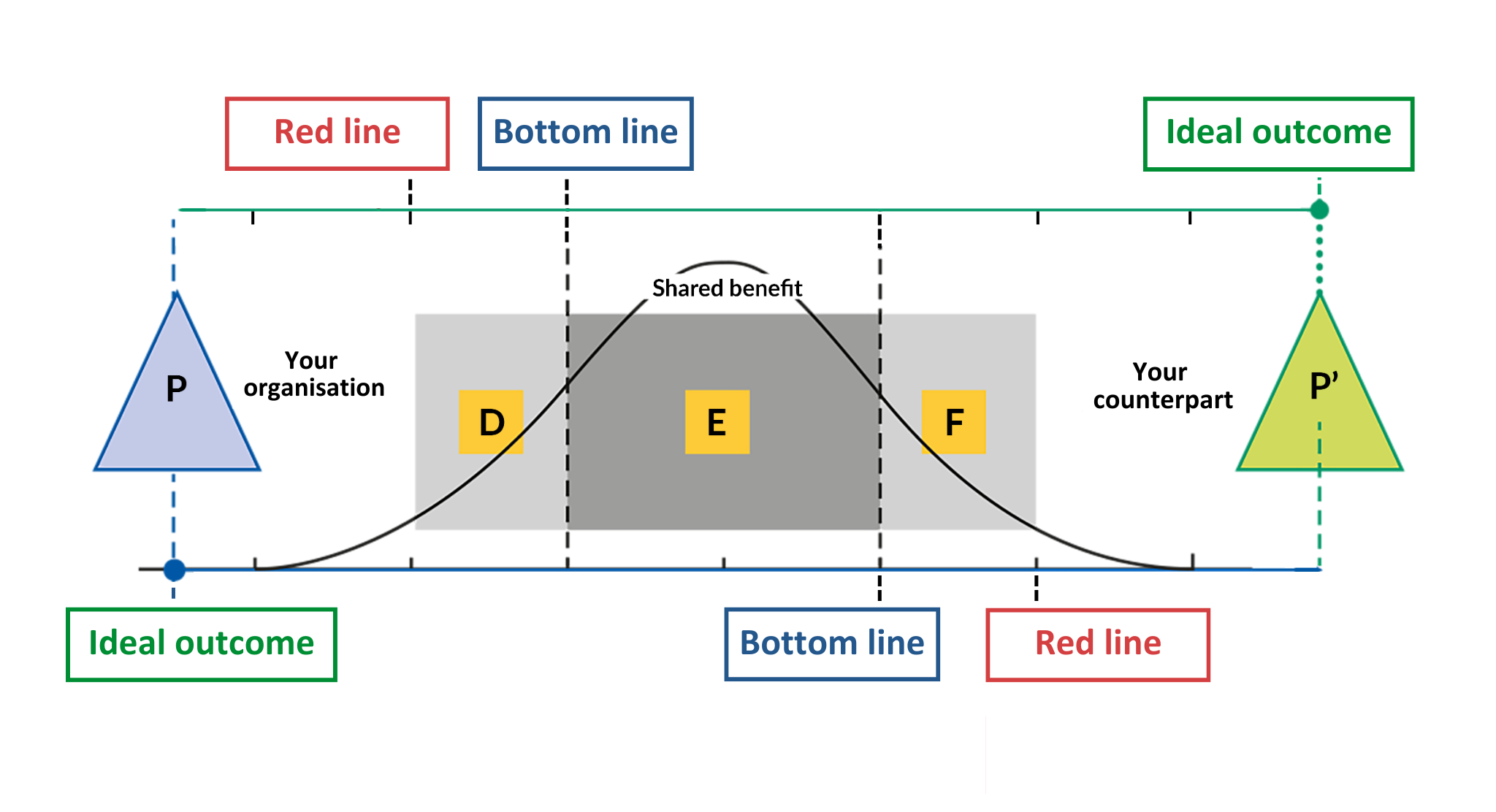

Once you have established your bottom and red lines and assessed the risks associated with each compromise, you’re ready to negotiate.

-

Scenario D: Favours your organisation but requires your counterpart to refer to their hierarchy. This scenario carries higher risks for your counterpart, who may accept the unfavourable compromise but lose trust in your organisation and become less open to dialogue in the longer term. Your counterpart can’t go beyond area D because it violates their red lines.

-

Scenario E: Mutually beneficial agreements within both bottom lines. This is where the negotiation can actually take place.

-

Scenario F: Favours mostly your counterpart, needing your hierarchy’s approval. Carries higher risks for you. You know that any compromise beyond area F is outside of your mandate and therefore beyond your red line.

The most beneficial solution is usually negotiated in scenario E, within both parties’ bottom lines and without overstretching too close to either red line.

When negotiating in scenario E, use these criteria to evaluate proposals:

-

Does this create value for both parties?

-

Are the risks manageable within our operational capacity?

-

Can we explain this decision to stakeholders and affected populations?

-

Does this maintain essential humanitarian principles?

-

Will this agreement be sustainable over time?

A ‘yes’ to all five suggests a sound compromise.

Remember…

When facing your next difficult negotiation decision, ask yourself:

-

Have I clearly defined my red lines and bottom lines?

-

Do I understand what creates value for my counterpart?

-

Can I articulate the risks and benefits of this specific compromise?

-

Am I operating within Scenario E (mutual benefit zone)?

By balancing these elements, you can navigate complex situations, ensuring that agreements not only meet your organisation’s goals but also contribute to lasting, positive impacts.

Good luck!