Homs, Al-Qarabis. The ICRC, joined by the Syrian Arab Red Crescent and Homs Electricity company, implements a project of provision and instalment of a medium voltage aluminum underground cable in People’s park medium voltage substation. The main cable will be feeding 4 neighborhoods: Al-Qarabis, Al-Gawta, Joura Al-Shia and City Center neighborhoods. (Photo: ICRC/Anas Kambal)

Humanitarian diplomacy and humanitarian negotiation are inherently intertwined and interdependent, and form part of the same concept. While the Centre of Competence on Humanitarian Negotiation’s (CCHN) community members are familiar with humanitarian negotiation in their day-to-day work, the concept of humanitarian diplomacy is perhaps perplexing when applied to an operational context. What does it actually mean? In this article, I discuss the relationship between humanitarian negotiation and humanitarian diplomacy, and how the latter can be understood through examples of its practice.

The term “humanitarian diplomacy” has been receiving increasing attention since the millennium onwards. While academics have paid less attention to the concept, the term is being used more and more frequently by humanitarian practitioners, organizations, and states in relation to their humanitarian, foreign and security policies. There are several actor-dependent definitions and interpretations, such as those created and used by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and countries such as Germany, Turkey, France and Norway. The first known use of the term “humanitarian diplomacy” in English in relation to a state was in 1912 in the USA.

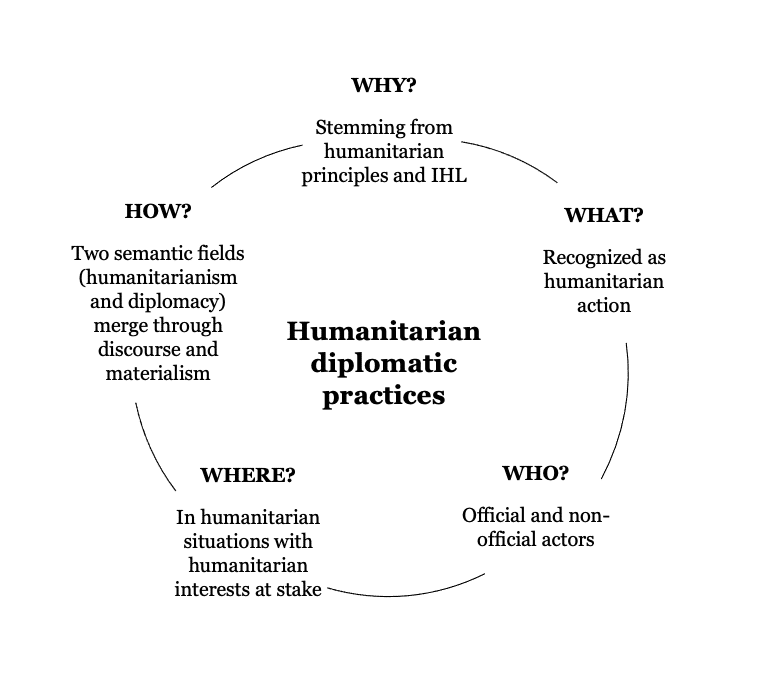

What exactly does the term mean? In short, it means advancing humanitarian interests and goals by diplomatic means. Instead of looking at an actor-specific interpretation of the concept, I propose that it is more useful to consider humanitarian diplomatic practices in order to understand how humanitarian diplomacy manifests in today’s world.

The overlap between humanitarian diplomacy and humanitarian negotiation

Before discussing humanitarian diplomatic practices, it is worth bearing in mind that humanitarian diplomacy and humanitarian negotiation overlap, particularly from a humanitarian negotiator’s perspective. Humanitarian negotiation can be seen as a specific function of humanitarian diplomacy in which the “frontlines of diplomacy” (Clements 2020) are the frontline negotiations humanitarians hold, particularly with armed groups who control a specific territory [1].

Humanitarian diplomacy is, in some ways, the umbrella term under which humanitarian negotiation and humanitarian mediation fall. All three have the same common goal: to advance humanitarian interests around the world in order to meet people’s humanitarian needs. Humanitarian negotiation deals with a specific country or borders of countries, situation and field-level stakeholders, whereas humanitarian diplomacy, is the global machinery that supports the creation of humanitarian space. Humanitarian diplomacy facilitates field-level presence and access, it helps secure infrastructure and funding, and it also establishes and maintains broad stakeholder relationships, such as private and public partnerships. To a certain extent, humanitarian negotiation is able to take place because of the humanitarian diplomacy that has preceded it. In turn, humanitarian negotiations and the presence of negotiators at the field level influence and inform further efforts in humanitarian diplomacy.

Although humanitarian diplomacy encompasses a broader range of activities and functions that go beyond humanitarian negotiation, the two are inherently intertwined. If humanitarian diplomacy is conducted without close cooperation with humanitarian negotiators and is not informed by negotiations at the field level, it risks becoming meaningless and ineffective. Similarly, if humanitarian negotiations are separate from humanitarian diplomacy, the negotiations will not reach their full potential and they will have a limited, and possibly short-lived, impact.

In negotiation settings, humanitarian diplomacy is embodied in a humanitarian negotiator. However, humanitarians are often puzzled when asked if they see themselves as humanitarian diplomats. This is partly because the term is somewhat oxymoronic: humanitarianism captures the ideals and principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality, and independence, whereas diplomacy, is seen as a game of compromise, negotiation, and pragmatism – and is therefore inherently more political. Nonetheless, it may be irrelevant whether humanitarians self-identify as diplomats or not, as others may still view them as such. Humanitarians are sometimes pushed to practice extremely conventional means of diplomacy, for example by host governments or powerful non-governmental actors, but having to do so means they can achieve their operational aims.

A recent example of the global construct of humanitarian diplomacy took place in relation to the conflict in Syria in which several humanitarian organizations work hard delivering humanitarian aid to people in need. One of the enablers of this action is the UN Security Council, which has authorized the cross-border delivery of aid into Syria for UN agencies. When this access was pending renewal and under negotiation in July 2020, humanitarians at all levels played an important role.

Information, practical examples, and experiences were gathered at the field level – across UN agencies, international organizations, and NGOs – so that operational data could support the case for continued access. The data provided to UN headquarters enabled UN actors, supportive member states, and other stakeholders to advocate for renewed access with the UN Security Council. Eventually, these diplomatic efforts culminated in an updated resolution, Resolution 2533, that provides for continued access through the Bab al-Hawa border crossing [3].

The five characteristics of humanitarian diplomatic practices

Successful humanitarian diplomacy becomes apparent in a number of ways: when aid is delivered efficiently, when support and resources for humanitarian action are secured, and when humanitarian issues are on the global political agenda and generate media attention. To understand the concept itself, one approach is particularly useful: to see how humanitarian diplomacy manifests through its practice. Humanitarian diplomacy takes place at international and national levels, with different levels of power. It also occurs as a high-level engagement and as humanitarian practitioners’ day-to-day business. The practices can be summarized as follows:

[2] Diagram created by Salla Turunen and published in The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 2020, Vol. 15, Issue 4. (Image: Salla Turunen)

This diagram helps humanitarian negotiators in two main ways. Firstly, it helps humanitarian practitioners recognize their own humanitarian diplomatic engagement and understand their own position in the global chain of humanitarian diplomacy. Secondly, it allows humanitarian negotiators to better position themselves in their local environment and increase their impact.

The next step for humanitarian negotiators is to consider their own point of view. At both local and international levels, humanitarian diplomatic practices originate from humanitarian principles and international humanitarian law (IHL). Humanitarian diplomacy often occurs because of these, but not always. Humanitarian principles and IHL guide interactions at the field level and they are, ultimately, understood to be a form of diplomacy, which is traditionally regarded as an outward representation of a polity.

The action taken in line with this humanitarian polity is understood to be part of humanitarian action, and humanitarian negotiation is one aspect of humanitarian action. Access negotiation, in particular, is a classic example of this, with negotiators trying to influence and persuade stakeholders to allow them to reach the people in need of humanitarian assistance. During these efforts, negotiators interact with all parties, both official and non-official, such as armed groups. This interaction with non-official actors is a distinctive feature of humanitarian diplomacy; several other forms of diplomacy are only concerned with official representatives.

Negotiations take place in humanitarian settings where people’s humanitarian needs are at stake. These needs are more obvious at the field level, but being able to meet humanitarian needs is also at stake in other settings, such as at meetings with important regional actors or high-level platforms like the World Humanitarian Forum or the UN Security Council.

Finally, how do you actually do humanitarian diplomacy? Simply put, you engage with humanitarian diplomacy as a representative of an organization; as a negotiator, this means being a representative in the field. Humanitarians personify humanitarianism and speak the humanitarian language, and their job is to advance humanitarian goals. The humanitarian diplomatic engagement has an impact within an immediate context, but it also feeds into the global level in two ways: through the international organizations that humanitarians belong to and through national-level politics that then extend beyond national boundaries and influence the international level.

To conclude, looking at humanitarian diplomacy through the lens of practice helps increase our understanding of what it means in reality. Ultimately, it is an instrument designed to create humanitarian space, to secure the resources needed for humanitarian action, to mediate between humanitarian principles and pragmatic realities at the field level, and to build the partnerships needed for humanitarian action. Humanitarian diplomacy implicitly acknowledges that humanitarian work goes beyond humanitarian operations, just as humanitarian diplomatic practices include and go beyond humanitarian negotiation. The CCHN community of practice is a unique platform where humanitarian negotiators can learn about and share experiences of humanitarian diplomatic practices and engagement.

[1] A.J. Clements, Humanitarian Negotiations with Armed Groups: The Frontlines of Diplomacy (1 ed.). 2020, Routledge, London and New York.

[2] H.A. Smith and L. Minear (eds.), Humanitarian Diplomacy: Practitioners and Their Craft, 2007, The United Nations University Press.

[3] S. Turunen, “Humanitarian Diplomatic Practices”, The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, Vol. 15, Issue 4, 2020, pp. 459–487.

This article builds on a recently issued research article, “Humanitarian Diplomatic Practices” by Salla Turunen, published in The Hague Journal of Diplomacy. Salla Turunen, a member of the CCHN Community of Practice, is doctoral researcher at Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) and the Department of Comparative Politics at the University of Bergen, Norway.