Resources

Digital Field Manual

Introduction

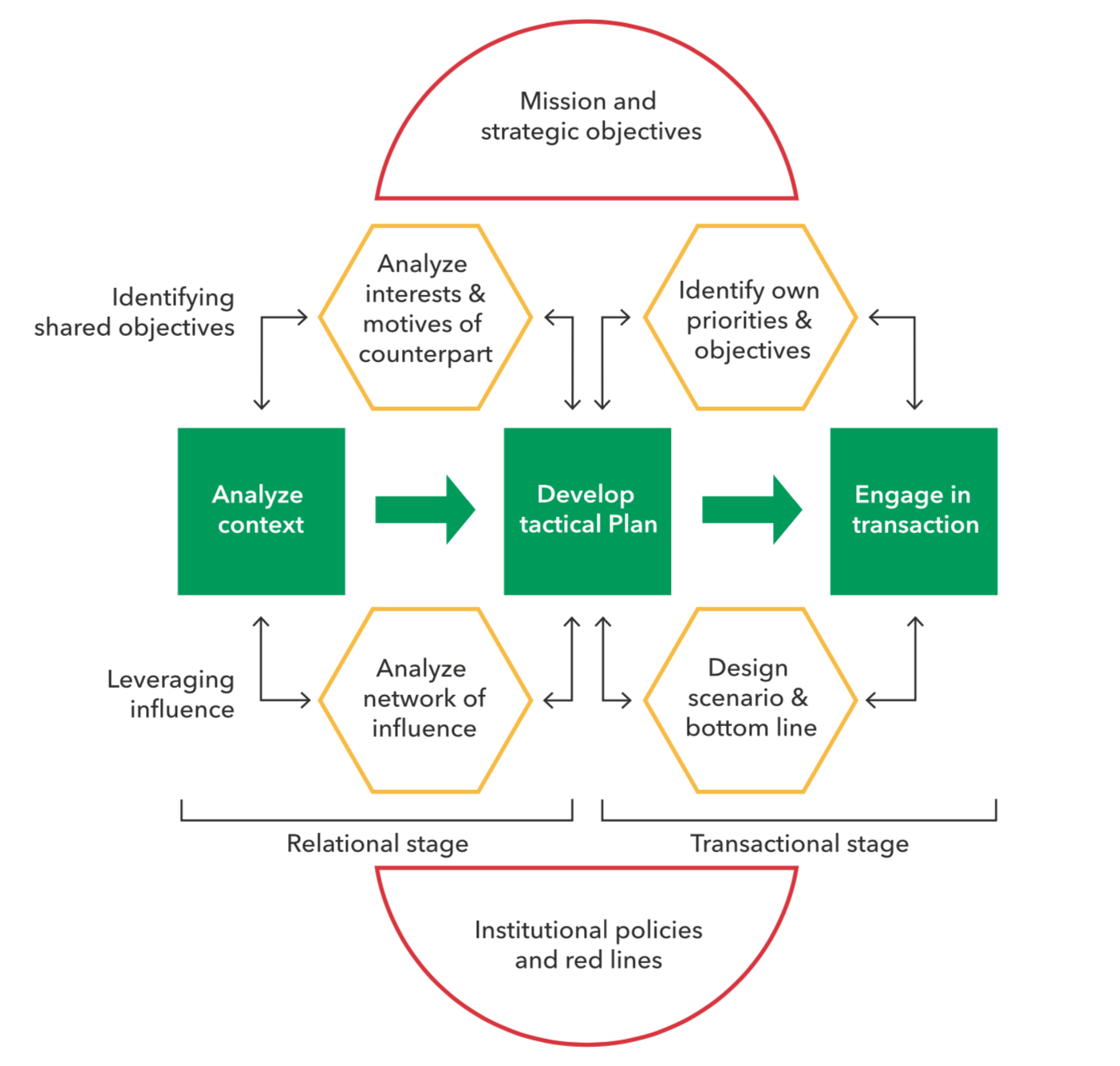

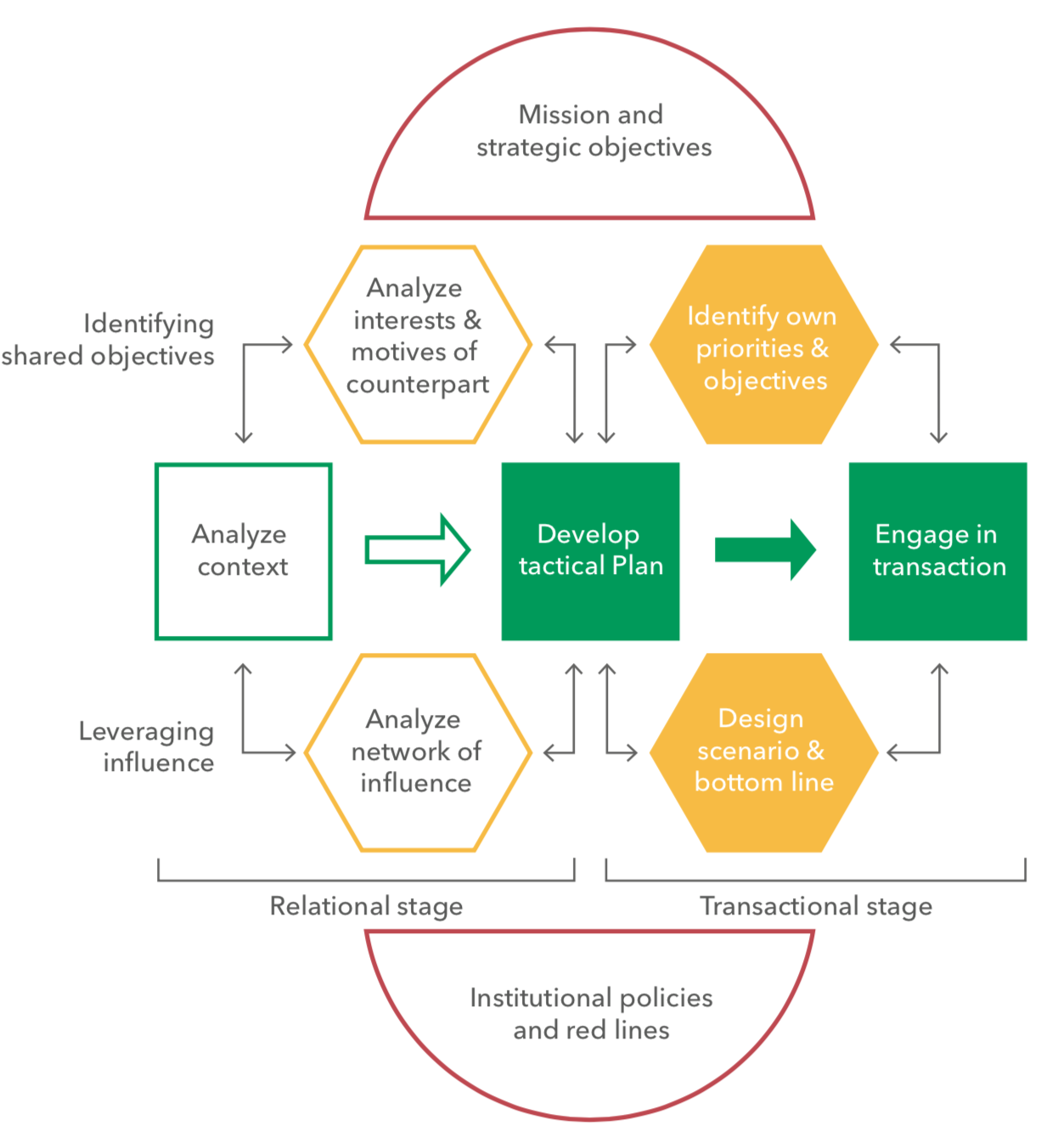

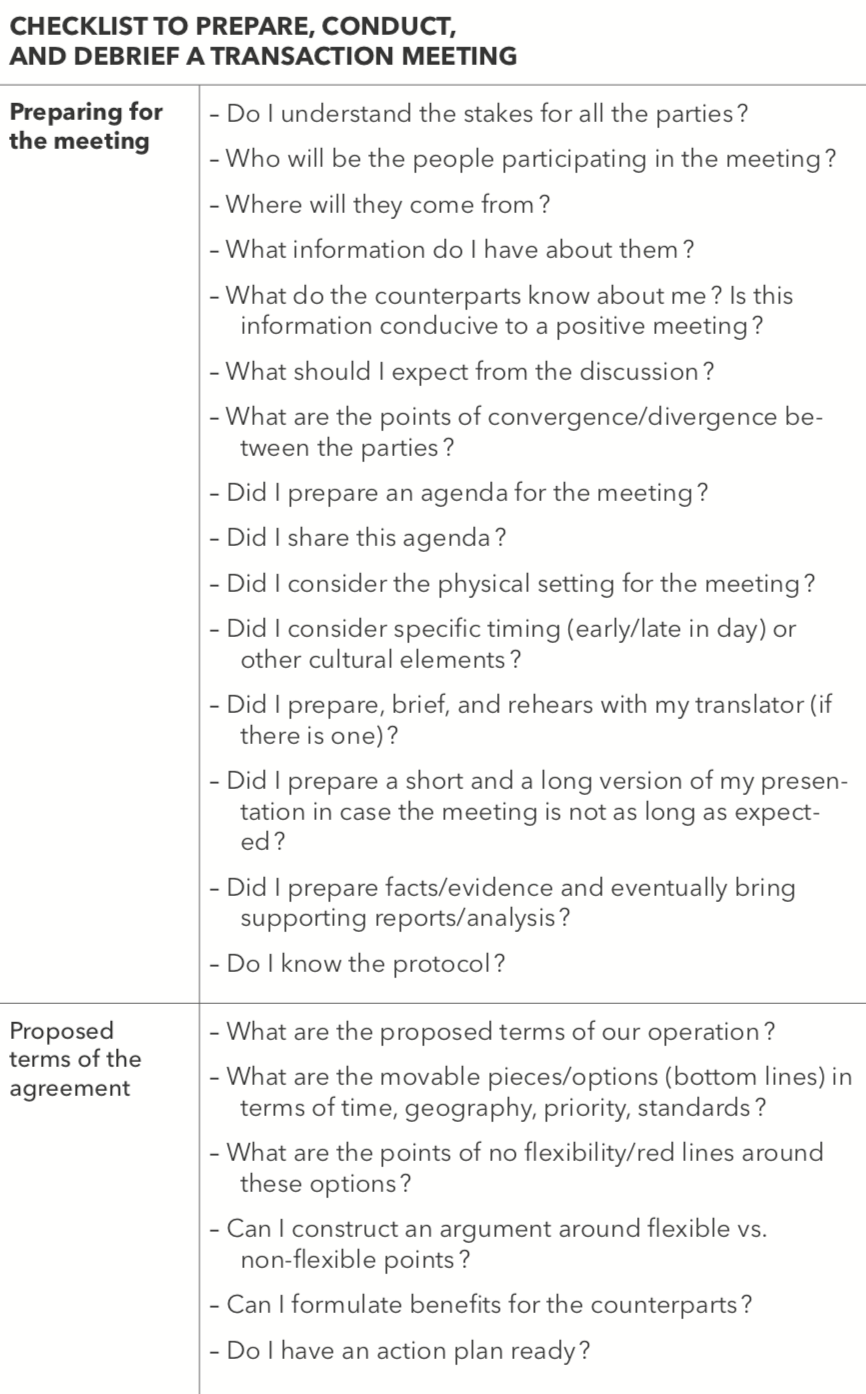

The objective of the Manual is to provide a comprehensive pathway to plan effective negotiation processes for humanitarian professionals on the frontlines. This section focuses primarily on the specific tasks assigned to humanitarian negotiators, including context analysis, tactical planning, and transaction with the counterparts. These tasks assume the support of the negotiation team accompanying the planning and review of the negotiation process (see 2 | The Negotiator’s Support Team); and the framing and guidance of the mandator based on the institutional policies of the organization (see 3 | The Negotiator’s Mandator ).

In this context, specific attention should be devoted to setting up a conducive environment for relationship building with counterparts in terms of:

- Gathering information on the situation and analyzing the political and social environment in which the process will be conducted;

- Developing tactical tools and plans to adapt the objectives of the organization to the specific environment and actors of the negotiation; and,

- Engaging in fruitful transactions in order to produce benefits on all sides.

This section provides critical tools to assist frontline humanitarian negotiators in the elaboration of their negotiation approach across these three steps.

The success of a humanitarian negotiation is contingent on the ability of humanitarian negotiators to build trust as part of ongoing relationships with the counterparts, to identify shared objectives, and to have the capacity to leverage influence through the use of networks of stakeholders.

As described in the Naivasha Grid, frontline negotiators have a central role to play in a negotiation process as they represent the organization in a personal relationship with the counterparts. Building on the empirical analysis of negotiation practices produced by the CCHN and research conducted by Harvard’s Advanced Training Program on Humanitarian Action (ATHA), one can observe that:

- Humanitarian professionals operating on the frontlines have primary responsibility for establishing and maintaining the relationships with the counterparts on which agencies hope to build the necessary trust and predictability required by their operations;

- These relationships should be understood as social constructs subject to the political, cultural, and social environments in which agencies operate; and,

- Understanding the context is therefore a critical step to preparing a humanitarian negotiation and engaging with the counterparts regarding access to the population in need, delivery of assistance, monitoring and protection activities, and enhancing the safety and security of staff, beneficiaries, and premises.

Introduction

Analyzing the conflict environment is an integral part of the work of humanitarian profes- sionals in the field. This task is of particular importance in frontline humanitarian negotiation in order to gather a solid understanding of the social, cultural, and political aspects of the situation and to build a trusted relationship with the counterparts. This analysis is further preparation for reflections with the negotiator’s team on the position, interests, and motives of the counterparts and the mapping of the network of influence, as presented in the Naivasha Grid.

These tasks are at the core of the relational stage of the negotiation aimed at building and maintaining a rapport with counterparts and other stakeholders. This stage is also a time for the negotiation team to reflect with the humanitarian negotiator in the lead, compare notes with colleagues from within and outside their organization and develop a critical sense about everyone’s perception of the conflict environment. These reflective and consultative tools are presented in the next section (see Section 2 Yellow) on the role and tasks of the negotiation team. For now, this section focuses on practical ways to sort information about the context of a negotiation in preparation for the development of a tactical plan.

A humanitarian negotiation generally begins with two competing narratives about a situation. On one side, an organization is expressing serious concerns regarding the needs of a population affected by a conflict and offers its services as part of the humanitarian response. On the other side, the authority in charge of the population or of the access to the region is putting into question the accuracy or reliability of the information presented by the humanitarian organization, criticize the priority of the proposed response or challenge the mandate of the organization. The core goal of the negotiation process is to find a way to reconcile these two narratives around some pragmatic arrangements.

In the early stage of a negotiation process, the quality of the information brought forward by the humanitarian organization is of critical importance in determining the chance of success of the negotiation. The traction of the information supporting the offer of service surpasses by far the gravity or urgency of its concerns. In fact, the more intense the concerns expressed by the organization, the more scrutiny they will attract from counterparts regarding the credibility of the sources and the reliability of the information.

Gathering quality information is often an undervalued stage of a negotiation. One can spend months negotiating access to an important location while missing critical information on the context, humanitarian needs, power networks, or other humanitarian actors operating in the area.

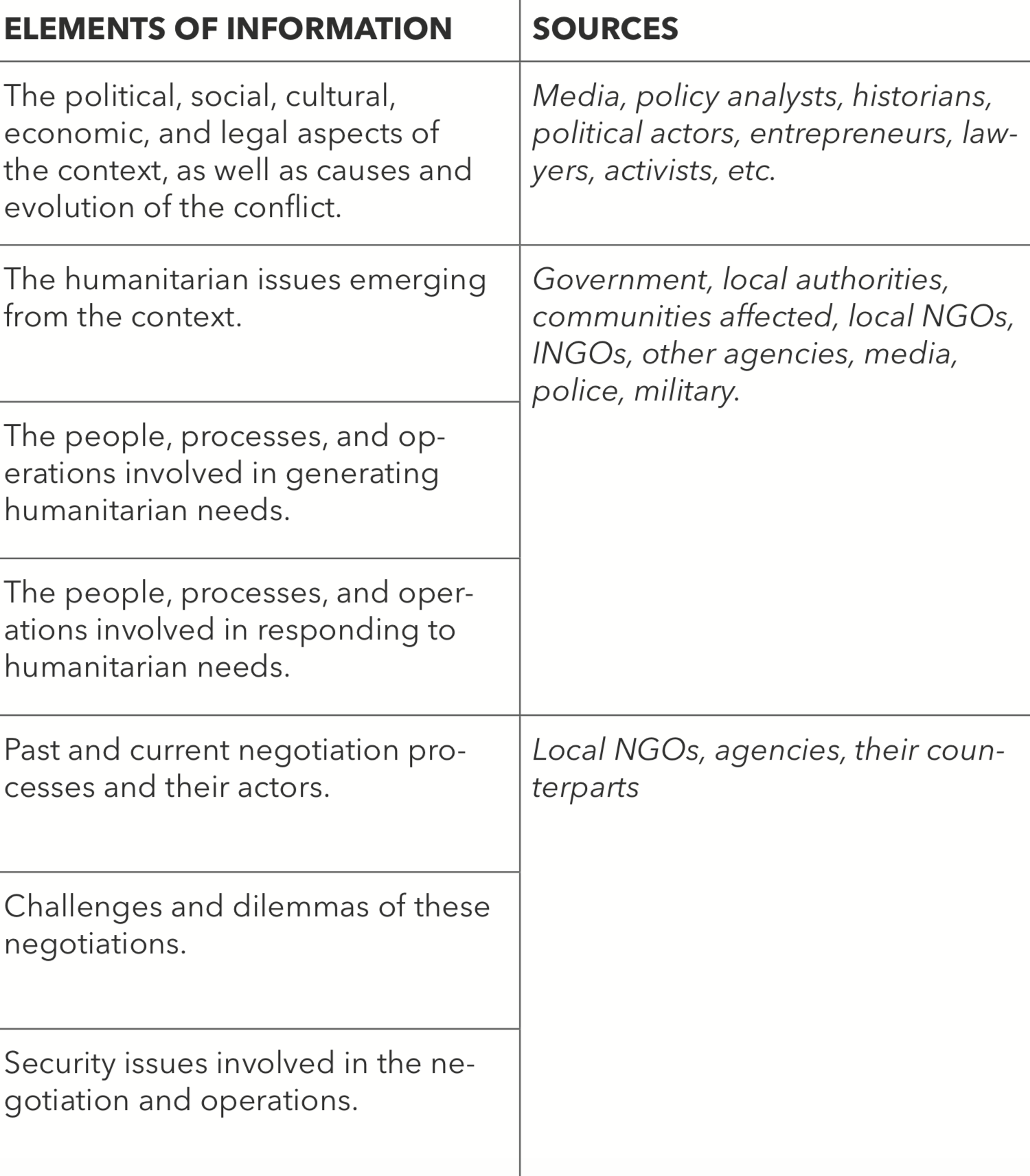

As a first step in planning a negotiation process, it is important to ensure that the negotiator and his/her team have all the necessary quality information about the context to establish and maintain the credibility required for the specific negotiation. The focus and depth of information will vary depending on the objective and environment of the negotiation.

While it may appear obvious, it is worth mentioning here some of the core issues and potential sources of information to start an analysis of the environment. The quality of information depends on several factors:

These factors are often interrelated: clear, unambiguous information tends to come from a trusted source, unaltered in its transmission, and easy to corroborate by third parties. Ambiguous and unclear information tends to have a problematic source or chain of custody and is usually uncorroborated.

There are several barriers to accessing quality information, especially on the frontlines, due to insecurity, suspicion, language, cultures, etc. Humanitarian organizations often find themselves relying on single-source assessments that can be easily instrumentalized, especially in tense environments. As a result, organizations often negotiate with a deficit of contextual information compared to the counterparts. The latter will often try to assess from the outset their “information advantage” in relation to how much the humanitarian negotiator does or does not know about the context, which will inform how the counterpart can leverage superiority in terms of access to information.

Unsurprisingly, counterparts in government or armed groups will not hesitate to bundle, hide, or contradict information from the humanitarian organization as a way to create confusion and uncertainty. The first defense against such tactics is to ensure that the negotiator has the best access possible to quality information from various sources in the preliminary stage of the negotiation process.

Enhancing the Quality of Information

A statement such as: “We have information that dozens of families are starving in the areas under your control.” will have a limited impact at the negotiation table if it is not properly sourced, detailed, and corroborated.

While information like: “A local church has informed us last week that 125 people suffer from severe malnutrition, 35 of whom are children. 12 children have been put on therapeutic feeding at the local clinic.” will add significantly more traction not so much because of its dramatic character but because it demonstrates the ability of the organization to collect detailed information based on local contacts and then corroborate this information with other medical sources.

A second challenge in sharing information with the counterparts is being unable at times to disclose the source of the information out of concern for the security of the individual or organization that provided it. In the case of a single-source assessment, one may not even be able to share the original information out of fear of reprisal against the individual source.

To counter such risks, organizations and negotiators should, by default, seek out multiple sources of information in politically tense environments in order to mitigate potential pressure against identifiable sources (e.g., humanitarian negotiators should meet several representatives of a community or local authorities to corroborate information over time even if they provide little added value to the information itself).

How to Evaluate and Sort the Quality of the Information

As discussed above, the planning of a negotiation requires the gathering of information about a number of issues, including, but not limited to, the humanitarian needs of the population. An organization’s moral authority (which may not be seen as such by the counterpart) is not enough to leverage influence on the counterpart. Quality information must be presented to the counterpart to support the request of the humanitarian organization, uphold the credibility and legitimacy of the negotiator, and respond to the needs of the population in the most adequate manner.

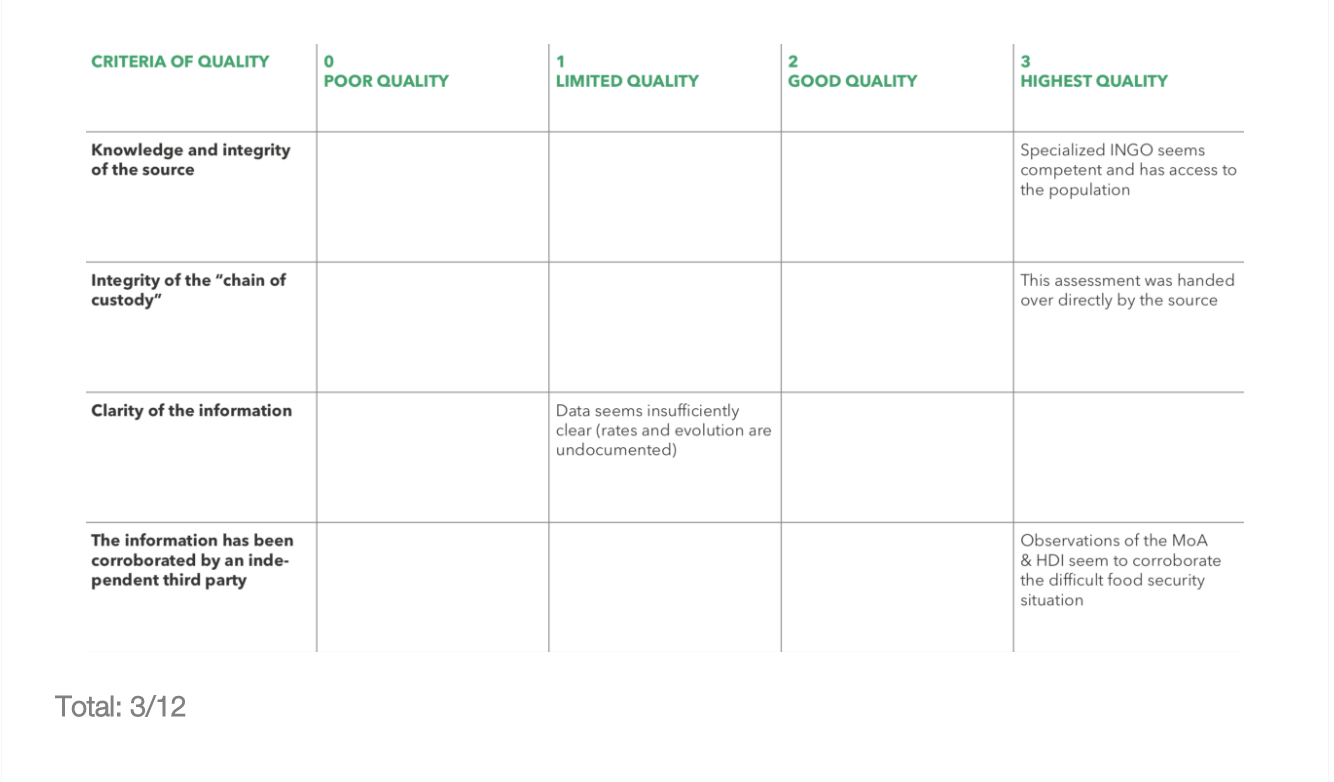

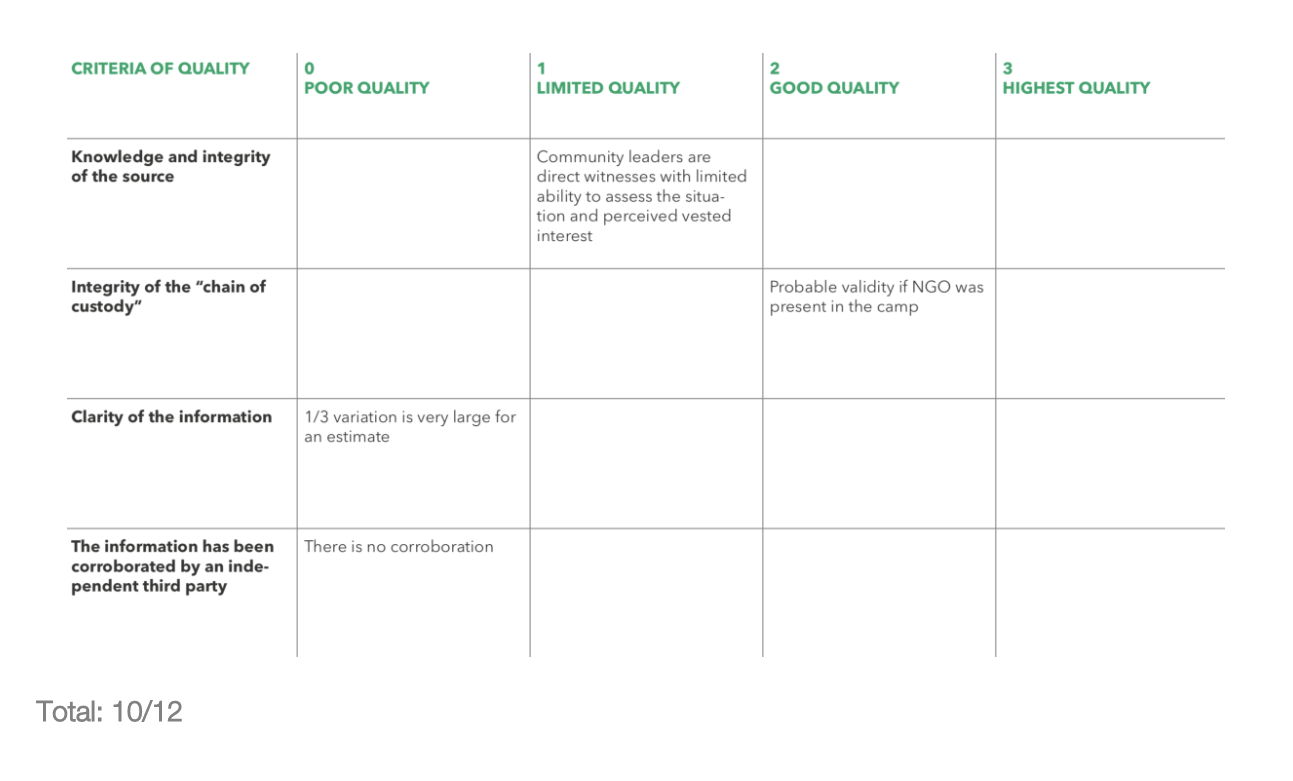

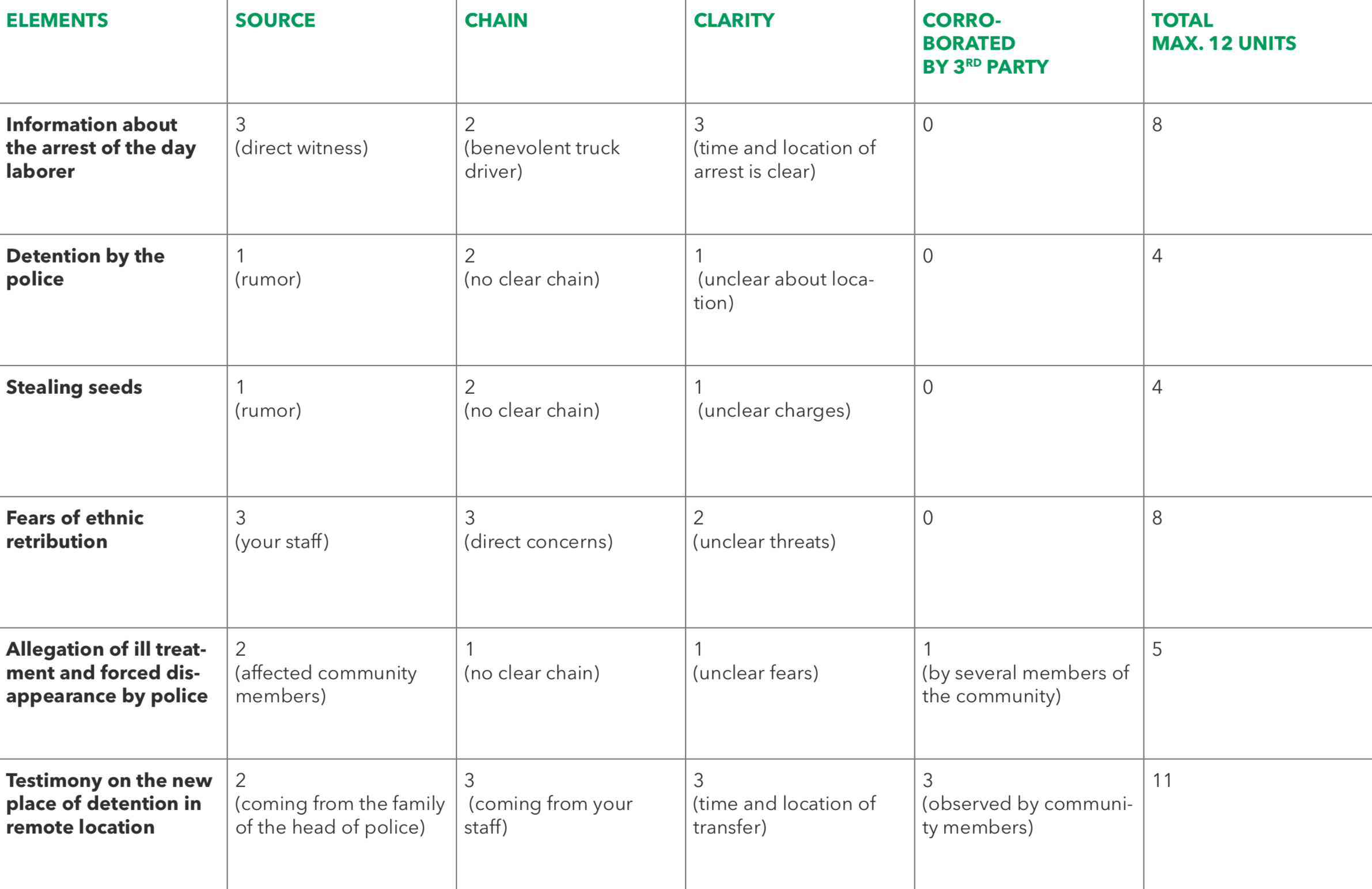

The quality of the information can be sorted in a straightforward way, assigning a degree of relative quality to elements of information by adding nominal values from 0 (poor quality) to 3 (high quality) for each criterion mentioned above. It provides for a scale of a maximum 12 units (3 degrees X 4 criteria) for each element of information.

For example:

As reported by a local NGO, Justice for All, community leaders estimate that there are between 20,000–30,000 inhabitants in Camp Alpha located on the outskirts of the city. What is the potential traction of this information as the negotiator meets with the authority to seek access to the IDP camp?

The information in this example will have limited value in the negotiation process in view of the uncertainty attached to it. Corroborating and narrowing the estimated number of IDPs could help considerably in improving the value of the statement at the negotiation table.

Another example:

A nutritional assessment in the remote district Alpha conducted by Food Without Borders (FWB), a recognized INGO and implementing partner of your organization, demonstrates an increase in rates of malnutrition over the last six months, affecting especially children under 5 suffering from chronic wasting. This assessment was confirmed in the latest report of Help the Displaced International (HDI), a UK church-based charity. According to the Ministry of Agriculture, the latest crops in the region yielded poor results due to the lack of rain, resulting, as observed by the local staff of FWB, in families selling household items in the market to be able to purchase minimal amounts of food. The situation is expected to worsen as winter approaches.

What is the value of this statement in terms of quality information as the negotiator meets with the authority to undertake a food distribution program in the district?

This statement presents high-quality information that may provide significant traction at the negotiation table. It could be further improved by gathering more detailed data on the evolution of malnutrition levels.

Analysis of the quality of the information can be amalgamated in one table which allows a sorting of priority elements based on their degree of quality, using the following example.

Example

Protecting a local staffer against retribution

A truck driver comes to the office UK charity Seeds for All (SfA), and informs the officer in charge that, according to the villagers, a day laborer of SfA has been arrested in the morning at the main crossroad of the village by armed men in civilian clothes. He adds that the rumor says that the day laborer has been detained by the police of the district. He is suspected of stealing some of the seeds being distributed by SfA.

In view of the ethnic profile of the day laborer, SfA staff fear that he could face serious physical retribution in police custody if he were detained overnight. There are allegations of other incidents of ill treatment and forced disappearance by the police circulating within the community.

Questioned by the local staff of SfA, the head of the local police station denied detaining the individual. After some time and several conversations with family members of the police chief, it appears that the individual was transferred around noon from the police station to a remote location deep in the rural area of the district. Community members reported to SfA local staff that they have observed a police car leaving the village with the day laborer at 12h30.

What information will the SfA negotiator use in the first meeting with the head of police to find a solution to this problem and get the release of the day laborer before nightfall?

The following table can be used to sort the validity of each element of the case on a scale of 0 – 3) 3 being the highest quality.

Elements of information will present various degrees of quality (from 0 to 12). Bundling the five statements as the overarching story weakens the starting position of this negotiation. As the negotiator prepares to meet with the police chief, the most authoritative information (> 6) in terms of traction appears as:

- 8 units: The day laborer was arrested in the morning at the crossroad by unknown men.

- 11 units: There is clear information that the day laborer was transferred by the police to a remote location in the rural area at 12h30 today.

- 8 units: There are fears of ethnic retribution.

The least informative and weakest elements (< 6) relate to:

- 5 units: There are unclear allegations of ill treatment and forced disappearance by the police.

- 4 units: There are rumors that the day laborer was detained at the police station in the village.

- 4 units: The day laborer is accused of stealing seeds distributed by SfA.

As a result, the representative of SfA should:

- Seek additional information to strengthen the case before the meeting (e.g., more details regarding the name and profile of the day laborer, the location of the police station in the rural area or information about the men who arrested him, allegations of ill treatment by the police);

- Skip over the weakest elements of information to increase the overall reliability of the case to be presented to the head of police; and,

- Recognize the limited information available but emphasize the trust in the strong elements.

Ultimately, the life and welfare of the day laborer will depend on the ability of the SfA negotiator to demonstrate from the outset, through the provision of quality information, the seriousness and networking capability of his/her organization within the political and social environment of the head of police. The negotiator should avoid introducing weak elements which will likely derail the process and strengthen the ability of the head of police to deny the involvement of his men.

Concluding Remarks and Key Lessons of This Tool

The gathering of quality information represents an important point of leverage in a complex negotiation and is a worthwhile investment in terms of time and resources. To draw an information advantage, the negotiator will need to diversify the sources of information and understandings of the situation to integrate new angles on central and lateral issues.

The credibility and predictability of the organization depend on the negotiator’s ability to discern the required quality of information in the eyes of the counterpart (i.e., the tolerance for uncertainties and vagueness). With relatively solid information, the negotiator will be able to project self-assurance and the right level of connections with the environment. Gathering such information takes time and requires specific skills.

One should note that the negotiator should not aim to become a substantive expert on the object of the negotiation. On the contrary, experts may destabilize the counterpart and prompt a withdrawal from the discussion. Humanitarian negotiators can always call on more expertise as the support structure of the negotiation process.

In this context, frontline negotiators should consider:

- Identifying all the key elements of the organization’s own narrative about a humanitarian situation and its context;

- Evaluating the quality of the information supporting the organization’s starting position using the proposed grid;

- Depending on the availability of time and resources, enhancing the authority of selected elements by narrowing the statement, verifying the source, testing the integrity of the chain of custody, and/or looking for a third party to corroborate the observation.

- Finally, selecting the most relevant and reliable information to be presented at the early stage of the negotiation process, demonstrating the seriousness, capabilities, and connection of the organization to the counterparts.

Humanitarian professionals have to acquire a good sense of the conflict situation to be able to operate in terms of population needs, programming, logistics, and risk management. Our common understanding of conflict environments is largely made of observable facts (e.g., hunger, insecurity, displaced populations, etc.) and commonly accepted norms (e.g., violent, tragic, disastrous, sad, etc.). These facts and norms form our reading of the reality. They also represent our vision of how we wish the reality would be construed by others. The reality is therefore as much an objective description of the environment in which we operate as a constructed “story” we use to project our vision and mission through it.

On the “kaleidoscopic” vision of humanitarian negotiators

Analyzing a context through a negotiation lens means integrating the counterpart’s subjective perspective into the equation, fully understanding that their vision of reality is an important building block of the relationship.

This “kaleidoscopic vision” of a situation can be easily confusing for humanitarian professionals, especially when the efficiency of their operation depends on an accurate appreciation of the situation based on solid and objective evidence of the population’s needs, the ongoing security risks, the required logistics, etc. Context analysis in a negotiation process should be distinguished from operational and technical analysis serving the planning of an operation and should include an appreciation of the counterpart’s perspective.

Recognition of the subjective nature of our understanding of “reality” is of importance in frontline negotiations, as the starting point of a negotiation process is generally a mix of divergent narratives about reality —i.e., the parties to the negotiation see the world differently.

The purpose of this module is to propose tools that will help humanitarian negotiators to better perceive the counterpart’s reading of reality and find areas of agreement in order to start the conversation about finding pragmatic solutions to the humanitarian needs of the population.

Understanding the Negotiation Environment

Addressing a famine situation through a negotiation process requires a solid understanding of the political, cultural, and social underpinnings of the environment and the role of food in the distribution of power between social players at the national, local, and even household levels, as well as of the potential divergent or convergent norms associated with the situation.

The negotiation environment requires not only a cultural and social fluency to understand the counterpart’s narrative, but also an ability to integrate often contradictory assertions into the agency’s own analysis and discourse as one strives to become more pragmatic. Hence, an operational agency may describe a “famine” situation based on factual elements such as the nutritional status of a population where the scarcity of food is threatening the lives of a large number of people. But “famine” can have a different normative reading based on political, cultural, and social values of the dominant group controlling access to food. In some negotiations, the determination of a “famine” situation may be welcomed by the counterpart; in others, it may be rejected by the counterpart regardless of the objective assessment of the agency.

This contextual dynamic applies to the application of international norms such as humanitarian access. Negotiating access does not require the parties to agree on the existence of an international norm of access. At times, the international norm will be recognized by the counterparts; at other times, the international norm will be rejected. Yet, access to populations can be negotiated on multiple grounds (e.g., moral, cultural, religious, professional, etc.) that may be more acceptable to the counterparts and communities affected. Parties to the negotiation may agree in effect about the implementation of an international norm without ever agreeing about the international norm itself.

Definition of a fact

Facts are observable elements considered by the observer to be true; things known to have happened or assertions based on a personal experience.

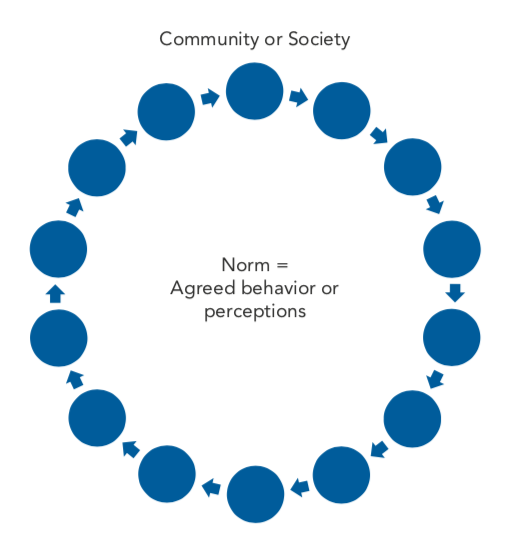

Definition of a norm

Norms are ways of behaving that are considered normal in a particular culture or society, or a desired behavior that a group of people believes in. Norms give meaning to communities that define themselves through their identity and common values.

This open-minded approach applies to determining features of an affected population in terms of age (e.g., who can be qualified as a child in the context), gender (e.g., access to women as vulnerable groups), social status (e.g., who should be recognized as the leaders). While agencies may consider these differences as the product of a lack of information on the side of the counterpart or a straight violation of an internationally recognized norm, negotiators should read beyond the apparent disagreement about facts and norms and remain cautious about such “disagreement.” This dissociation between the operational and advocacy roles of an organization and humanitarian negotiation often require setting up a well-articulated mandate establishing the negotiation space with distinct roles (see 3 | The Negotiator’s Mandator) so as to avoid creating confusion in the implementation of the agreement where the two realities (the agreed subjective vision of the parties vs. the objective vision of the operators) may clash.

Advocacy vs. Negotiation

Humanitarian agencies have two distinct and at times conflicting roles. On the one hand, they have been established to promote and be the guardian of the core values of humanity in some of the most challenging environments. They should observe and report on violations of internationally agreed norms. On the other hand, they are mandated to find pragmatic solutions with parties to armed conflict to ensure the assistance and protection of the most vulnerable populations. The latter role involves seeking a common understanding about the relevant facts and norms. The point of a humanitarian negotiation is not to prove one vision is superior to the other but to build a trustful relationship conducive to reaching an operational agreement.

The quality of the context analysis therefore depends on the ability of the humanitarian negotiators to overlay the appropriate cultural, social, or political filters on their reading of the situation to find the correct interpretation in the eyes of the parties. The point of junction of these subjective visions is referenced later as the island of agreements of a negotiation process, where a relationship of trust can be built despite the differences of view on issues on the negotiation table. In this sense, the relational stage of a negotiation process portrays the most agreeable facts and most convergent norms supporting the search for a pragmatic agreement between the parties.

What might seem paradoxical is that, for a negotiation to take place, even on the most contentious issue, several agreed facts or converging norms must be in place to allow the conduct of the negotiation process. Any disagreement entails a number of intertwined agreements on facts and convergence on norms. To engage in a negotiation process, parties need to concur, even if implicitly, on selected elements. In other words:

- To disagree effectively on facts (e.g., denying the prevalence of a famine in a particular context), parties implicitly need to agree on some norms (famine-stricken population would have the right to food);

- Conversely, to disagree effectively on norms (e.g., denying the existence of a right to food), parties implicitly need to agree on some facts (the prevalence of a famine situation).

What Are Negotiable Facts?

Facts that may be discussed in a factual negotiation include:

- Number and features of the beneficiary population

- Location of this population

- Technical terms of the assistance programs (time, date, mode of operation)

- Nutritional and health status of the population, etc.

Norms that can be discussed in a negotiation process include:

- Right of access to the beneficiary population

- Obligations of the parties

- Legal status of the population

- Priority of the operation, etc.

Building an Island of Agreements

Building a relationship with a counterpart requires deliberate steps to ascertain a space of agreement between the two parties drawing from the paradox of frontline humanitarian negotiations. Once the negotiator has been able to sort out the facts and norms of a given negotiation environment, the next step of the context analysis is to understand which of these facts are agreed (shared and accepted by both parties) or contested (where one party has a different view or understanding of the factual elements), and which norms are convergent (as a shared belief between the parties) or, on the contrary, divergent (as the products of two separate social constructs.) The two examples below are drawn from current practice and are presented to illustrate the process.

Example 1

Factual Negotiation: Contested Facts/Convergent Norms

In a discussion with the representative of International Food Relief (IFR), an international NGO, the Governor in charge of the IDPs (internally displaced persons) in the Northern District of Country A is contesting IFR’s assessment that there is severe malnutrition among the displaced population in a specific camp within his district. According to him, there is no actual malnutrition among the displaced and thus no need for the humanitarian agency to implement an emergency nutritional program for them. However, there is, in his view, malnutrition in other parts of the District among local communities, and he asks IFR to assist these populations under IFR’s humanitarian mission. IFR did not observe comparable levels of malnutrition in the host community.

In Example 1, the Governor is contesting the fact presented by IFR that there is severe malnutrition within the IDP camps. The Governor argues that the food should be distributed among members of the host community where malnutrition is, in his view, “real.” There are two visions of the reality that are in conflict. The focus of this factual negotiation between the Governor and IFR will be to demonstrate the prevalence of malnutrition rates among the IDPs compared to the local population while building on a dialogue on the shared (although implicit) norms regarding alleviating hunger and the recognition of the experience, expertise, and mandate of IFR. The compromise will probably take the shape of a technical distribution scheme that provides for the IDP population most in need while also alleviating hunger within the host community as long as it can be documented as a recognizable fact for IFR.

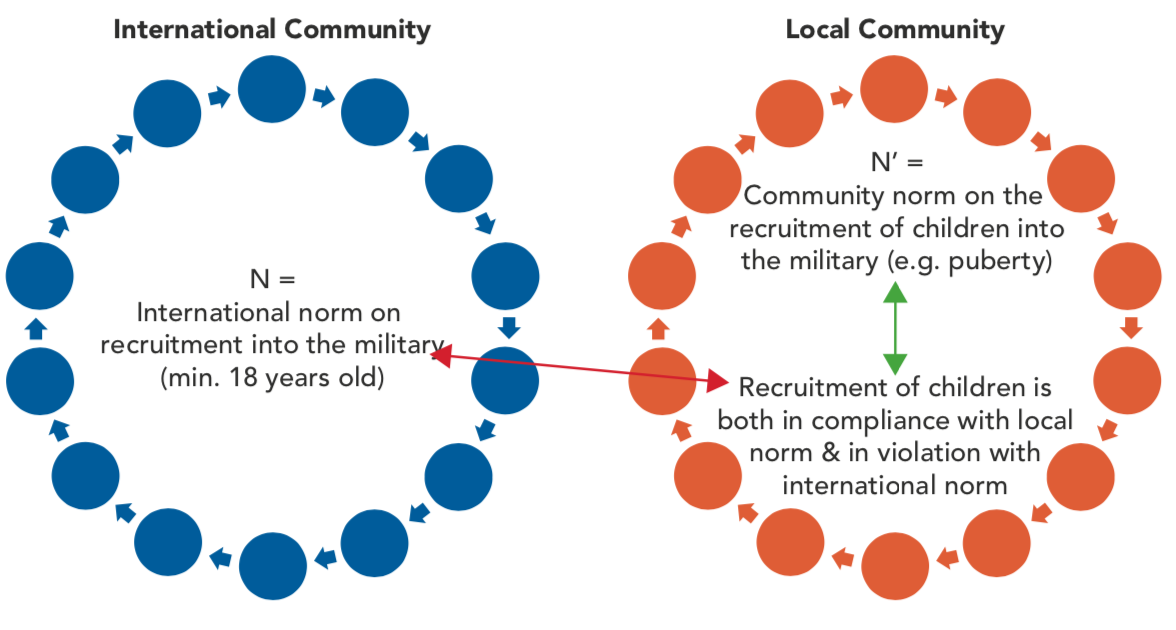

To engage in a normative negotiation, one has to understand that norms are essentially shared beliefs of a community or society. Normative negotiation always implies a conflict of norms between international standards or policies of the organization and the norms of the counterparts controlling access to the territory and population. These are two sides believing in two distinct desired behaviors. There is thus a tension between these two norms and societies.

Example 2

Normative Negotiation: Agreed Facts/Divergent Norms

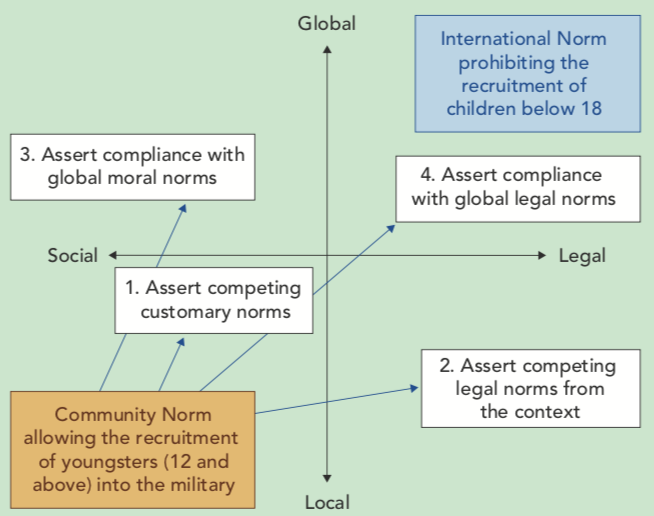

Several hundred boys as young as 14 years old are openly recruited every year into community-based militias under the control of the military of Country A, which is engaged in an armed conflict with rebel groups in rural areas. While international law prohibits the recruitment of children under 18 years, the military commander and community leaders of the district explain to the representative of Children Protection International (CPI), the INGO wishing to provide medical assistance, that they believe that a boy becomes an adult by joining the community militia from the age of 14 years as a cultural sign of bravery and courage. CPI wonders if providing medical assistance to child soldiers in this context is facilitating the recruitment of children and therefore contributing to the commission of a war crime.

In this example, the fact that 14- to 17-year-old youths are recruited into armed militias is not in question. The issue of the negotiation is to determine the applicable norm, i.e., to what extent recruitment of 14- to 17-year-olds is “normal,” and to determine which group will be the culture or society of reference (e.g., the youths themselves, the community affected by this practice, the military of Country A, or the international community).

Ultimately, should CPI consider the recruitment of these young persons as “normal” vs. “abnormal” in their program of assistance, and how far can the convergence on norms be as a precondition to medical assistance? When one is facing a normative negotiation, the negotiation will deal with differences in political, social, or cultural norms, which are much more difficult and riskier to compromise on (e.g., a “deal” around 16 years old as an agreed norm between CPI and the commander could be as inappropriate as 14 or 18 years old.) Here the negotiators will need to address the social consensus around the recruitment of children and its cost/benefit for the affected community while building a dialogue on some observable facts (e.g., number of children recruited, their health status, etc.).

One may argue that such dialogue can take place only with some recognition of the factual benefit (to the counterpart’s culture) of youth recruitment (bravery and adult rituals) as well as the negative impact on minors of being part of the militia. Ultimately, the job of the negotiator is not to resolve the conflict of norms but to find a way for CPI to operate in favor of 14- to 18-year-olds despite the conflict of norms (e.g., binding an assistance program with dissemination of information on international law).

Application of the Tool

This segment presents a set of practical steps to engage in a proper context analysis of a negotiation process. There are three main steps to the analysis of a complex negotiation environment.

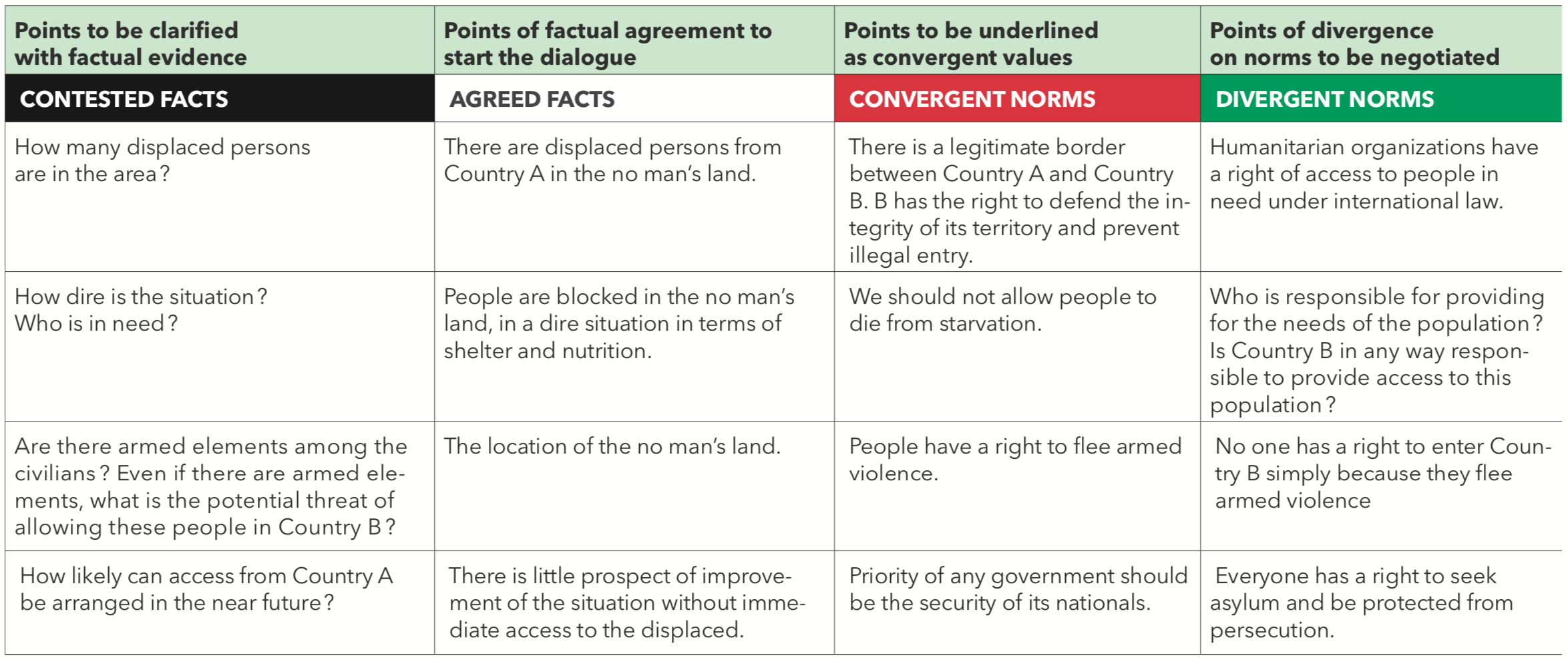

Step 1: Sorting and qualifying elements arising in a negotiation environment

The first step is the identification of the key facts and norms of a humanitarian situation, drawing from the narratives of the humanitarian agency and its counterpart(s), the parties to the negotiation process. Once these main facts and norms have been identified, one should determine facts that are agreed vs. those that are contested, and norms that are convergent vs. those that are divergent, between one’s agency and the counterpart(s). For example, taking the narrative of a fictive situation on the border of Country A and Country B:

Example

Providing Aid to Displaced Persons in the No Man’s Land

A large number of displaced persons seeking refuge from armed violence in Country A have been blocked in a makeshift camp in the no man’s land between Country A and Country B.

Country B has denied access to its territory, arguing that the displaced persons have no right to enter its domain. Representatives of Country B doubt that there are very many of them and are not sure about their precise location. According to data collected by local NGOs, the nutritional situation in the makeshift camp has been deteriorating steadily over the past few days.

Humanitarian organizations are seeking access to the population in need from the territory of Country B. They call on the humanitarian obligations of Country B to allow immediate access across its border. Country B is rejecting these appeals, arguing that: 1) numbers are exaggerated; 2) many of the displaced are in fact dangerous armed elements; and 3) assistance should come from the territory of Country A, which has the responsibility to provide for the needs of its nationals.

Due to the conflict situation, it is unlikely that humanitarian organizations will be able to access the population in need from Country A in the near future. While Country B recognizes the importance of humanitarian values, it intends to prioritize the security of its nationals.

One needs first to filter:

- The agreed facts (between the humanitarian negotiator and the counterparts)

- The contested facts (by any of the parties)

- The convergent norms (between the humanitarian negotiator and the counterpart)

- The divergent norms (by any of the parties)

A large number of displaced persons seeking refuge from armed violence in Country A have been blocked in a makeshift camp in the no man’s land between Country A and Country B.

Country B has denied access to its territory, arguing that the displaced persons have no right to enter its domain. Representatives of Country B doubt that there are very many of them and are not sure about their precise location. According to data collected by local NGOs, the nutritional situation in the makeshift camp has been deteriorating steadily over the past few days.

Humanitarian organizations are seeking access to the population in need from the territory of Country B. They call on the humanitarian obligations of Country B to allow immediate access across its border.

Country B is rejecting these appeals, arguing that: 1) numbers are exaggerated; 2) many of the displaced are in fact dangerous armed elements; and 3) assistance should come from the territory of Country A, which has the responsibility to provide for the needs of its nationals.

Due to the conflict situation, it is unlikely that humanitarian organizations will be able to access the population in need from Country A in the near future. While Country B recognizes the importance of humanitarian values, it intends to prioritize the security of its nationals.

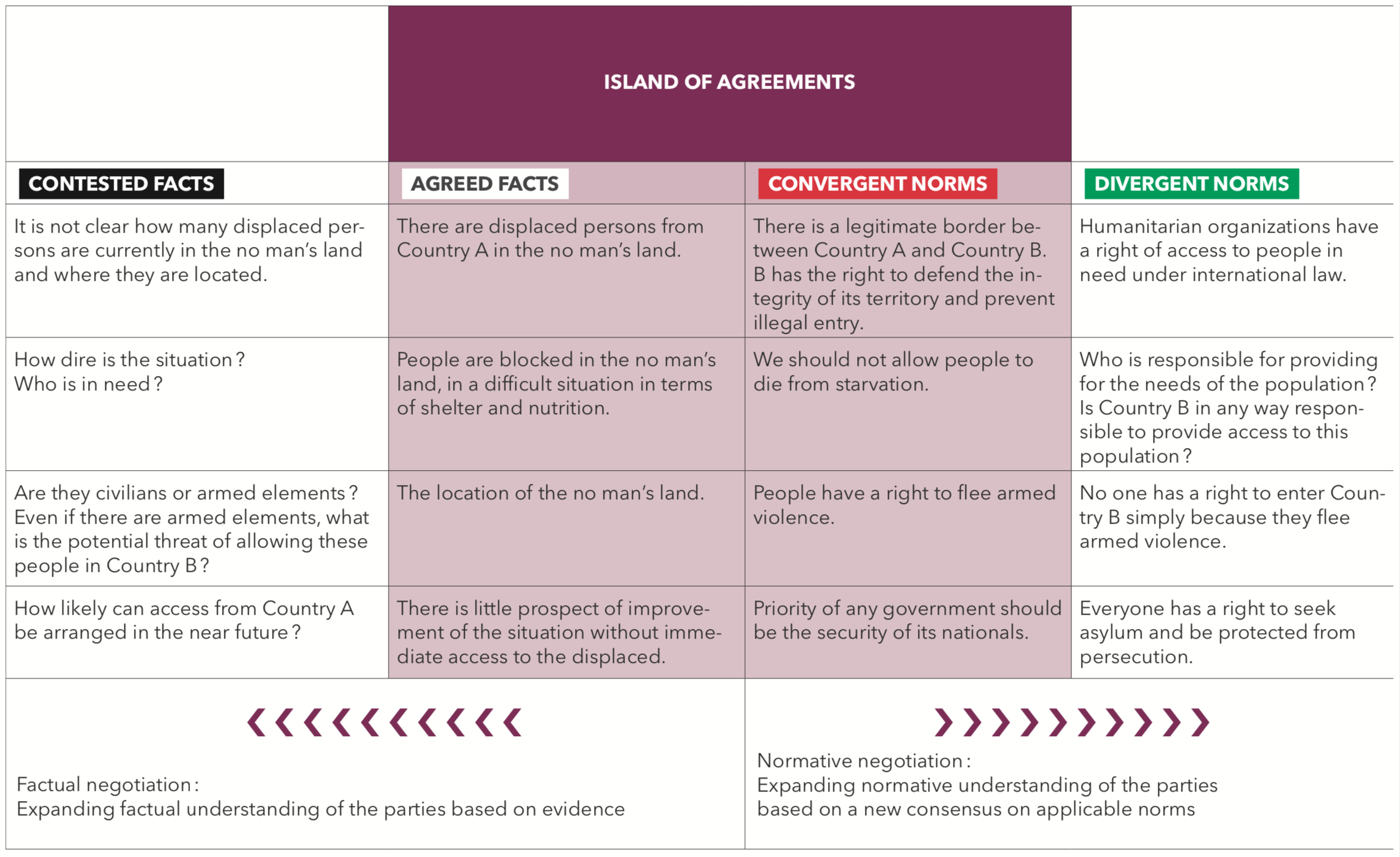

Step 2: Recognizing which areas of the conversation are most/least promising in the establishment of a relationship and which concrete issues will need to be negotiated with the counterparts

The second step of the process is to determine the nature of the upcoming negotiation (factual or normative) and identify the inherent areas of agreement/convergence on which a negotiator can start establishing a dialogue. Based on this determination, the negotiator can prepare a series of issues from the most to the least agreeable/convergent points to be discussed and proceed in defining the pathway of the negotiation based on a relationship-building approach.

The facts and norms of the case mentioned above can then be sorted based on the narrative collected and put in specific columns:

Click on table for full screen mode

In this example, facts of the case about the existence of the displaced population, its location, and its needs are mostly uncontested. Some additional facts may need to be clarified as part of the introductory dialogue on the context. Some norms are shared as well. The focus of the negotiation per se will be on the normative issues at stake, namely, who is in charge of responding to these needs, what are the motives to reject access from Country B, and what are the responsibilities toward this population.

Step 3: Elaborating a common understanding with the counterpart on the point of departure of the discussion while underlining the specific objectives of the negotiation process

Every negotiation is composed of areas of agreement and areas of disagreement. The point is to identify the areas of agreement and decide if one should focus on negotiating factual issues through the collection of data and building on shared norms or focus on negotiating normative issues, shaping a new consensus, and building on shared understandings of facts.

In this particular case, there are strong indications that the negotiation would be more normative than factual. The main issue at stake is the right of a humanitarian organization to cross the border of Country B into the no man’s land to provide assistance to a population in need, which is a normative issue, and not so much about the features and vulnerabilities of the affected population. Even in the best-case scenario of agreed facts, CPI would not get access because of a normative divergence on its right of entry across the border of Country B. While there are some disagreements or need of clarification on facts, these factual disagreements are not central to the negotiation.

Building on this analysis of the context, the humanitarian negotiator can set the terms of the discussion from the outset, enabling the building of a relationship with the counterpart as one of the key goals of generating a transaction and allowing the organization to operate in the environment.

Click on table for full screen mode

In this particular case, one may consider focusing on agreed facts as a point of departure:

- Inquiring about the location of the displaced populations;

- Discussing the food security situation on the border based on factual information the local organizations may have gathered;

- Trying to identify jointly the needs of the population as a way to plan an operation;

- Planning the logistics of the supply chain to the affected populations.

Based on these points of potential factual agreements, one may consider building a rapport on the humanitarian values and norms of assisting these populations and clarifying the threats associated with humanitarian access to the populations in need from Country B. Moving from this “island of agreement,” humanitarian negotiators can then focus on the more difficult issues of normative access to the population.

Interestingly, the same analysis can be done with a factual negotiation (vs. the preceding plans for a normative negotiation), starting with a statement on converging norms if these represent a more solid basis for a dialogue with the counterparts and then delving into contested facts about the existence of this population.

In such case, one may consider:

- Reviewing the legal framework of humanitarian organizations working in the country and discussing their professional experience working in sensitive border areas;

- Discussing the terms of welcoming refugees in the country;

- Discussing ways to prevent security risks associated with cross-border activities;

- Setting planning for major assistance programs at the border.

Based on these points of convergence at the normative level, one may consider building a rapport on the factual dimension of the current crisis and the current needs of assisting these populations in the no man’s land from the territory of Country B.

Concluding Remarks and Key Lessons of This Tool

Conducting a proper context analysis of a negotiation environment is a critical component of a negotiation process. This analysis is distinct from operational or security assessments as it puts the subjective appreciation of counterparts front and center.

In this sense, frontline negotiators should consider:

- First distinguishing factual from normative elements of the negotiation environment, discerning between agreed and contested facts, and convergent from divergent norms.

- Looking for agreed facts and convergent norms as potential points of departure of a dialogue with counterparts to build a positive and predictable relationship before addressing the issues of tension. These potential points of departure will later on allow the emergence of a space of compromise between the parties and of practical and feasible options.

- In a factual negotiation (i.e., bridging different understandings on facts), aiming to demonstrate the facts through evidence and expertise while recognizing the convergence of norms.

- In a normative negotiation (i.e., bridging different understandings of what is “normal”), navigating the tensions between the two norms while agreeing about facts and exploring the spectrum of possibilities to find a pragmatic solution that provides benefits to all parties.

- Taking some distance from their own understanding of objective facts and international norms (i.e., avoid being dogmatic about one’s perceptions) so as to be able to listen and understand the arguments of the counterparts. Negotiators are mandated not to convince the other side about one version of reality or to ensure compliance of the institutional norms but rather to find workable solutions to a humanitarian problem within some limitations specified in their respective mandate.

Introduction

Analyzing the conflict environment is an integral part of the work of humanitarian professionals in the field. This task is of particular importance in frontline humanitarian negotiation in order to gather a solid understanding of the social, cultural, and political aspects of the situation and to build a trusted relationship with the counterparts. This analysis is further preparation for reflections with the negotiator’s team on the position, interests, and motives of the counterparts and the mapping of the network of influence, as presented in the Naivasha Grid.

Humanitarian negotiation is centered on an effort of frontline negotiators to build a trustful and predictable relationship with their counterparts as a way to create a conducive dialogue and seek the consent of the parties to assist the affected population. The degree of consent may vary depending on the willingness of the counterparts to accept or simply tolerate the presence and activities of humanitarian organizations.

In increasingly fragmented environments, the role of humanitarian negotiators is gradually shifting from gaining acceptance to seeking a minimum of tolerance toward the presence and activities of humanitarian organizations. Maintaining access amounts to managing risks while ascertaining the limits of the receptivity of local leaders and communities toward humanitarian action. Proximity to the field, regular contacts with counterparts, and empathy toward local concerns are paramount to the success of humanitarian negotiation and the safety of staff in these environments. Ultimately, access should never be taken for granted or understood as a license to operate at will in a conflict environment. Rather, the work of humanitarian negotiators entails ongoing efforts to engender a “suspension of suspicions” toward the presence and activities of their organizations.

While this principled approach is the most consistent with humanitarian actions across conflict zones, it has also been put to the test in increasingly complex and fragmented environments such as Afghanistan, Somalia, or Yemen, where the control over territory is challenged by governments or a multitude of armed groups that may prohibit the access of agencies to vulnerable populations. Hence, humanitarian organizations find themselves managing varying degrees of consent and opposition among diverse conflict actors as well as shielding themselves from violent opposition elements opposed to their presence. The “bunkerization” of humanitarian organizations is, consequently, affecting their ability to build trust with the parties and further amalgamate the perceptions of the counterparts regarding the political character of foreign organizations.

From Humanitarian Entitlement to Humanitarian Engagement

Humanitarian negotiation is no longer only about seeking the unilateral consent of individual counterparts to allow the agency to operate in a rigid “principled space,” but rather building the resilience of agencies to operate safely in increasingly unpredictable operational spaces with multiple stakeholders and multilayered agendas involved. A useful concept is “humanitarian engagement,” focusing on the degree of predictability and trust one can derive from the relationships with the parties in the particular circumstances. As a result, agencies’ access to vulnerable populations is as good as the intensity and quality of their engagement with all the parties concerned.

Yet, the humanitarian space has been under increasing pressure by the expansion of peace enforcement activities and the imposition of counterterrorism restrictions on relief programs. Humanitarian agencies have been further confronted with the rapid instrumentalization of their relief and protection activities by political actors, host governments, and donors. This politicization of aid has in turn pushed agencies to engage proactively with counterparts and find pragmatic compromises between the needs of the population, the tactical interests of the parties, and the priorities of the agencies. Humanitarian negotiators play a key role in dealing with the increasing permeability of the humanitarian space as it defines the new limits of humanitarian action in polarized environments. Hence, humanitarian negotiation implies a tactical shift from a discourse of entitlement around access to one built on cooperation and trust between the parties and stakeholders. Managing these relationships has become a critical aspect of the negotiator’s tactical plan.

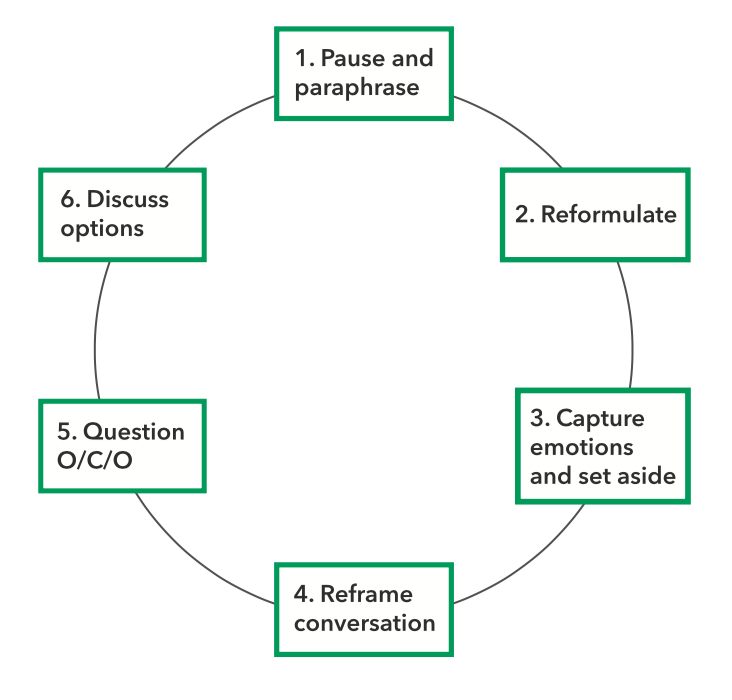

The fact that a counterpart rejects the terms of an operation is by no means the end of the humanitarian negotiation. It represents only a moment in a relationship. All humanitarian negotiators, even the most agile, are bound to reach the limits of acceptance of their counterpart. Their capacity to maintain the interest and trust of the counterparts in these circumstances is key.

Therefore, humanitarian negotiators must work with the best information available on the conflict situation, its actors, their interests, motives, and values, as well as their network of influence, to develop their engagement over time. This leads to the development of a tactical plan, based on the shared values and tactical interests of the parties to the negotiation. The tactical stage of a negotiation is geared toward establishing the basis of a frank dialogue to support a set of necessary political, professional, and technical transactions with the parties and maintain their continued support. As every agreement entails costs and benefits, as well as various risks for the parties, the main objective of this stage is to create a viable relationship between the parties that will resist time and shifting interests. Building on the context analysis detailed in the previous segment, the tactical stage of the planning is informed by additional analyses by the negotiation team that will inform the design of the tactics.

Among these, one can find in 2 | The Negotiator’s Support Team specific tools to work with the negotiation team to:

- Analyze the position, tactical reasoning, values, and motives of the counterparts;

- Map out the relationships among the stakeholders and analyze the network of influence;

- Identify the priorities and objectives of the negotiation, as a critical point in the design of the tactics;

- Set the scenarios and bottom lines of the negotiation, framing the tactical plan.

These four elements are optimally part of the role and responsibility of the negotiation team in support of the frontline negotiator and should be informed by discussions among the team in the field based on the observations of its members.

The following modules will focus primarily on the tactical angle of the frontline negotiators, which involves:

- Fostering the legitimacy of the negotiator and building trust;

- Determining the type of the negotiation and adapting the engagement strategy accordingly; and,

- Addressing a genuine conflict of norms through a normative negotiation.

Shifting from a space of humanitarian entitlement to one of humanitarian engagement represents a significant transformation of the ethos and work method of humanitarian professionals as they get involved in complex environments. While humanitarian agencies have been advocating for a recognition of a right of access to vulnerable populations based on humanitarian principles for several decades, frontline humanitarian negotiators have been increasingly relying on their ability to foster legitimacy and build a trustful relationship with their counterparts to seek and guarantee this access. This relationship and its implied equality of the parties become the central asset to cultivate. In this context, this Manual proposes a two-step approach for humanitarian negotiators to enhance the legitimacy and build trust addressing:

- The sources of legitimacy of the humanitarian negotiator; and

- The ways to build trust with the counterparts in these sources.

The importance given by a counterpart to a negotiation process relates not so much to the object of the negotiation per se but rather to the legitimacy of a humanitarian negotiator and his/her organization in the eyes of that party. Fostering legitimacy refers in this sense to nurturing the appreciation of the counterpart concerning:

- The features of the negotiator in terms of character and profile that need to be calibrated to respond to the expectations and rationale of the counterparts;

- The mission and mandate of the humanitarian organization as well as its track record in similar contexts;

- The relevance of the objectives of the humanitarian negotiation in the particular situation, the responsiveness of the agency to the needs of the population, and the support the agency garners from all the stakeholders.

The neutral, impartial and independent character of a humanitarian organization depend on the degree of recognition of these features by the parties to the negotiation.

These elements are the main building blocks of the perception of legitimacy in the eyes of the counterparts. It does not suffice to argue that because an organization is neutral and impartial it is therefore legitimate. Such assertion needs to be examined, understood, and trusted by the counterparts under the specific circumstances. In other words, the humanitarian nature of an organization is by essence a reputational issue.

Humanitarian negotiation is first and foremost about cultivating relationships with parties who can impact upon the welfare of the population affected by an armed conflict.

Since this Manual focuses on the specific role of the frontline negotiator, this segment will articulate legitimacy and trust through the viewpoint of the individual negotiators rather than the ones of organizations and systems. The legitimacy of the humanitarian negotiator as well as the one of the counterpart play a critical role in the success of humanitarian negotiation. Major concessions are obtained by virtue of the personal status and skills of frontline negotiators. Conversely, misperceptions about the negotiator’s status or insufficient personal skills may be critical impediments to access in some conflict environments. This point could easily undermine the confidence of many professionals in the field, as no one can feel totally assured that they have the status and personal skills required to seek access to people in need or feel certain that what they bring to the negotiation will be sufficient to guarantee the security of an operation.

The importance of the personal nature and social status of a humanitarian negotiator cannot be overestimated. Counterparts often rely on the integrity and reputation of an individual representative of a large humanitarian organization to ultimately decide on the scope of access to populations in need.

The most important skill a negotiator needs to have is to be able to understand the sources of legitimacy required in a particular context and adapt one’s personal profile as much as possible to that context. The point here is not to construct a misleading identity but rather to understand that some aspects of one’s identity and status may be more or less conducive to building a relationship in a specific context. It is about modifying one’s communication style more than shaping a new identity. And it is about listening to expectations and resistance from the counterparts, even if there are questions regarding personal characteristics, and being ready to adjust the personal and organizational profile in the context up to the point of finding a substitute person for a particularly sensitive negotiation.

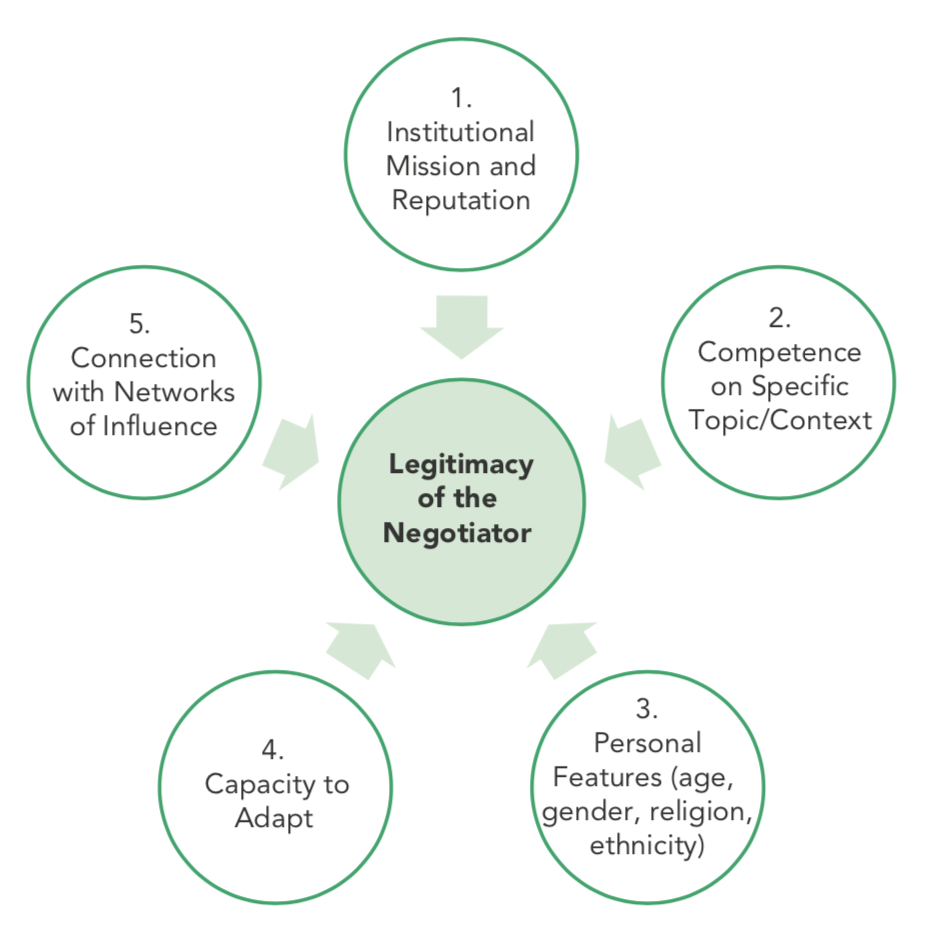

In practice, there are five sources to the legitimacy of the negotiator:

Balancing the Sources of Legitimacy

Not all sources of legitimacy are of equal value in all circumstances. Understanding the five sources of legitimacy will help to identify the relative value of each source in a given situation. This model can be used within the negotiator’s team to reflect on how one can increase his/her authority and legitimacy in order to create a trustful relationship with the counterpart and enhance the chances of success of the negotiation. This model can also be used to identify the most appropriate team member to be designated as a negotiator.

A negotiator should map out his/her individual characteristics with the support of objectively critical colleagues and set the terms of that profile in a given negotiation. He/she could then identify the most vs. the least conducive characteristics and opt to emphasize the positive characteristics while keeping the least conducive ones away from the conversation.

For example:

In a highly normative negotiation with a traditional and suspicious community leader:

a) Legitimacy is derived mostly from sources that can mitigate the risk of disruption from an unknown external organization, e.g.:

- Personal features (more advanced age, social and marital status, established religion, gender);

- Proven ability to adapt (lowering the risk of social embarrassment and confusion);

- Connection with networks of influence (that can vet your abilities and integrity).

b) Legitimacy is derived least from sources that can increase the risk of disruption, e.g.:

- Institutional mission and reputation (the more normative the mission, the more disruptive the mandate will be perceived);

- Competence on topic and context (the more scientific the approach, the more disruptive the competence may become).

Therefore, a frontline negotiator dealing with a counterpart from a traditional environment should emphasize the following sources of legitimacy:

- Age, family status, family experience if appropriate;

- Diversity of field experiences;

- Personal networks with scholars and community leaders in the region.

The negotiator should avoid:

- Talking about the legal basis of the organization’s mandate in international law and detailing the history of the organization from its inception onward;

- Citing, for example, the number of Nobel Prizes the organization received; or,

- Mentioning his/her Ph.D. on a subject seemingly related to the context (e.g., Social Anthropology or History of the Region).

Conversely, in a highly technical/professional environment—for example, dealing with a high-level military commander from an organized army or a director of a large hospital:

a) Legitimacy is derived mostly from sources that can validate the expertise of the negotiator, e.g.:

- Institutional mission and reputation (the more reputable the organization, the more recognized the mandate will be);

- Competence on topics and context (the more scientific the approach, the more comfortable and interesting the conversation will be);

- Personal features (showing rigor in terms of behavior and presentation);

- Connection with networks of scholars and experts (including the location of advanced studies).

b) Legitimacy is derived least from sources that can show a lack of integrity in terms of professional standards, e.g.:

- Interpersonal capacity to adapt (having worked on several types of missions in several capacities may not be the main asset).

The above approaches may appear either naïve or too simplistic, but they are in service to the overall goal. The point is to make sure that, while not creating a false sense of identity, some part of your character does not unwittingly become a liability undermining your effort to build a trustful relationship in terms of:

- The organization you work with;

- Your specific competence or lack of competence in a specific domain;

- Your age, gender, religion, ethnicity;

- Your capacity to adjust and shape your profile;

- Your network.

Being aware of your assets and liabilities can help significantly in building the right profile with the counterparts and establishing a safe space for a dialogue on the frontline. Your team, especially national colleagues or those from the particular area or group, can help in discussing these aspects.

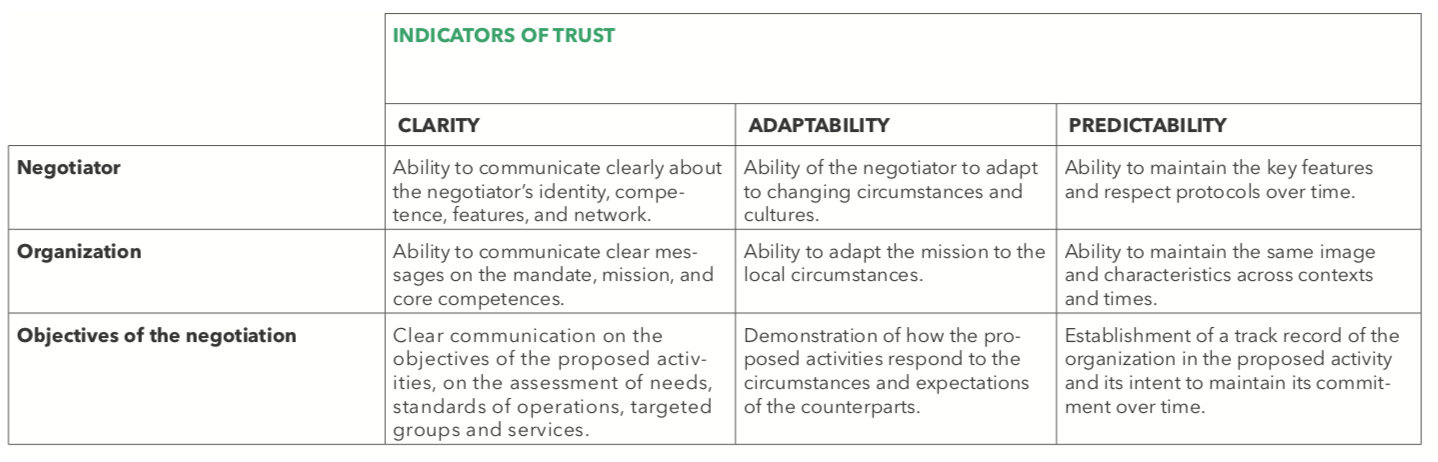

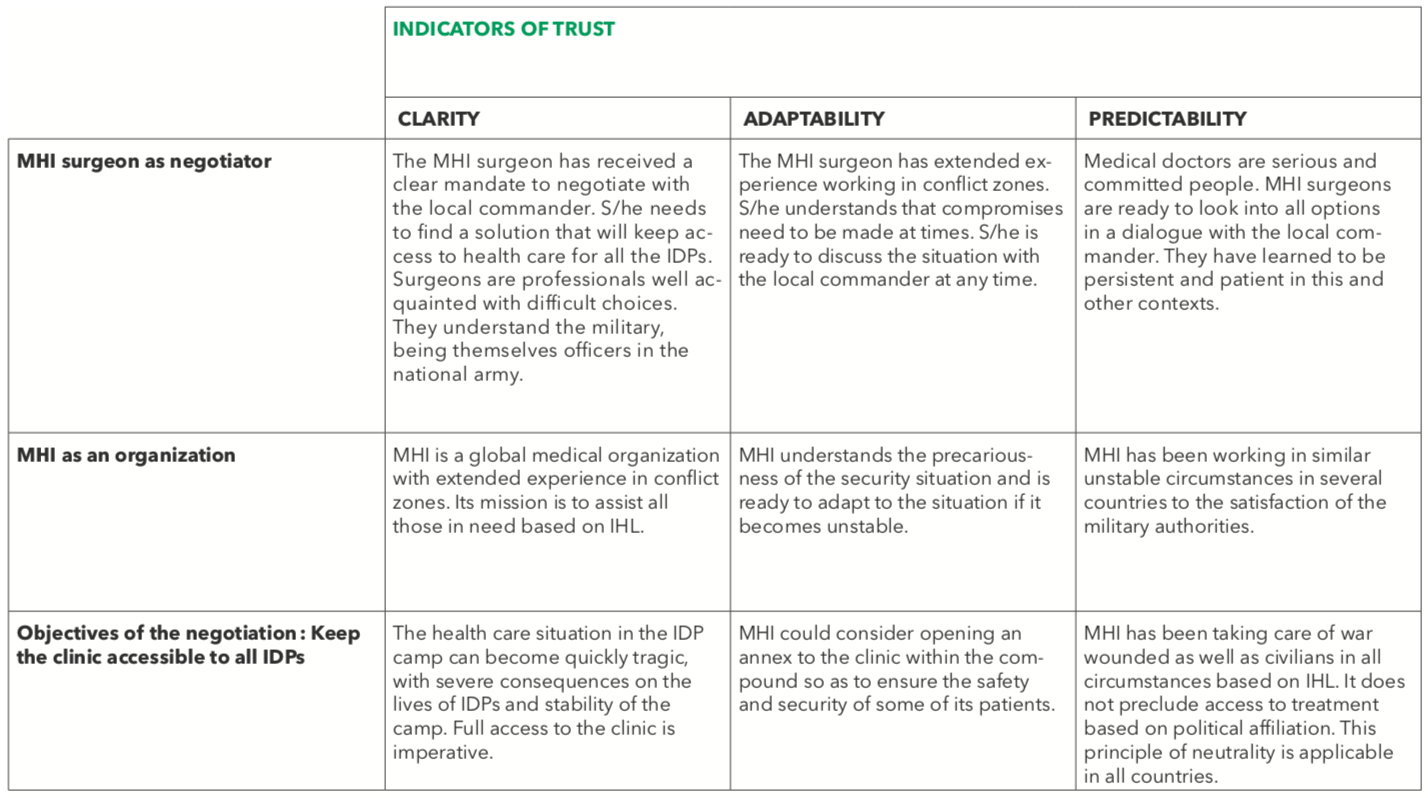

Building Trust in the Sources of Legitimacy of the Humanitarian Negotiator

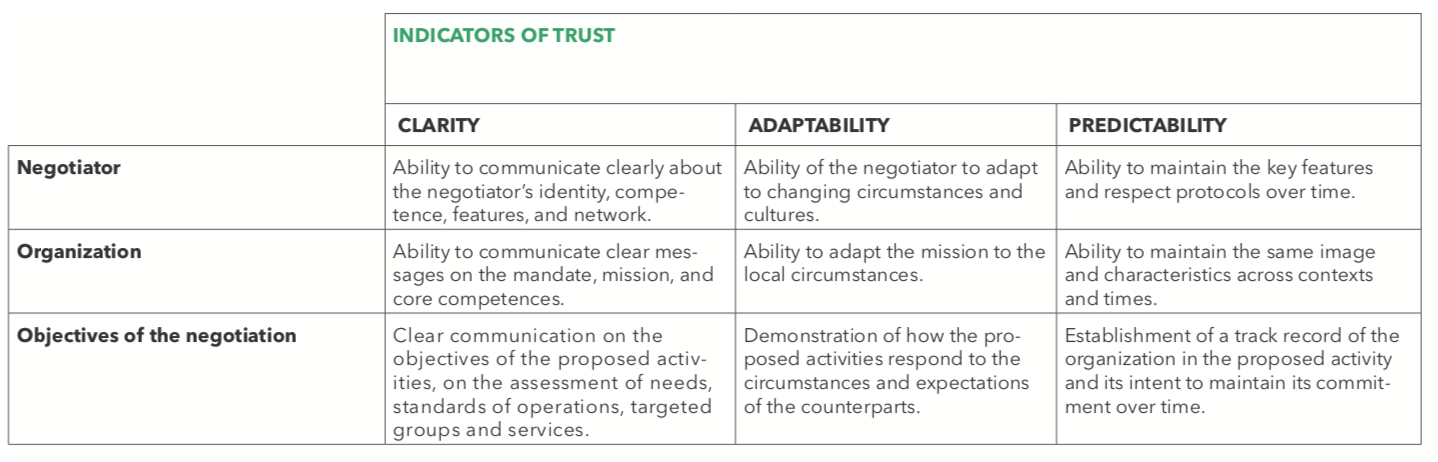

The subjective legitimacy, i.e., as perceived by the counterparts, depends on the ability of the negotiator to mobilize the firm belief of the counterpart about his/her sources of legitimacy (i.e., the humanitarian organization, the objectives of the negotiation, and personal features of the negotiator.) The counterpart’s belief is a derivative of the ability of negotiators to:

Predictability is one of the key assets of a negotiator as it allows the preservation of a shared space, language, and protocol of a negotiation in which both parties are trying to find a fair compromise between their competing interests.

Application of the tool

Hence, to foster legitimacy and build trust in a negotiation, a negotiator should be able to communicate about his/her organization, project, or personal features using the indicators of trust mentioned above.

Example

Location of the health clinic in a military compound

The internationally recognized NGO Medical Help International (MHI) has opened a primary health care clinic in the vicinity of a large IDP camp in the Southern District of Country A. The camp houses over 200,000 people, many of them in poor health after weeks of forced displacement by the military, which intends to cut the local population’s supply route and support to the armed rebels in the region.

The local army commander suspects that several militants are hiding among the IDPs and are using the MHI clinic to seek treatment after being wounded or falling sick in combat. By providing this assistance to armed rebels, he argues, MHI is providing material support to a group listed as a terrorist organization by the government of Country A.

The local commander requires you to move the MHI health clinic within the military compound adjacent to the IDP camp to ensure that no rebel can seek health care treatment from MHI. If MHI declines to move, MHI will have to close its operations in the district. There are no alternative sources of care for IDPs in the district. MHI argues that all wounded and sick have a right to seek health care under the Geneva Convention. MHI is also concerned about the possibility of illegal taxation of IDPs wishing to get access to the clinic in the military compound. Overall, MHI is concerned about the safety and security of its staff if they are associated with the military presence in the District.

You, as an MHI surgeon and former military officer with extended knowledge and connection with the community, are mandated to find a solution to this problem.

Drawing from the case above, a negotiator can apply the legitimacy grid and see how s/he can enhance trust of the local commander in the role and position of MHI.

In this case:

Concluding Remarks and Key Lessons of This Tool

This segment provided specific tools to enhance the legitimacy of the organization, objectives of the negotiation, and more specifically the frontline humanitarian negotiators. It underlined the importance of building trust as a form of capital in a relationship, understanding that the test is always in the eyes of the counterpart.

In this context, frontline humanitarian negotiators should consider:

- Drawing a critical analysis of their sources of legitimacy in terms of organization, objectives of the negotiation, and themselves;

- Identifying the most appropriate member(s) of the negotiation team to conduct the negotiation based on her/his sources of legitimacy and agility to build trust;

- Ascertaining for each of these sources the degree of clarity of the messages, adaptability of the strategies and tactics, as well as predictability of behaviors and attitudes in the negotiation process;

- Unpacking notions and legal norms such as humanitarian principles to ensure that the counterparts have understood the meaning of this concept within the given context; and

- Enhancing the sources of legitimacy of the negotiators by analyzing the critical elements in the context (e.g., level of education/experience vs. mandate vs. local connection vs. adaptability vs. gender/age/religion, etc.). It is important to select the most conducive characteristics and focus on them in the communication about oneself.

This module is designed to assist humanitarian negotiators in determining the type of negotiation they engage in and guide them in the development of their tactics at the negotiation table.

Negotiation is a vast domain of human engagements. Above and beyond humanitarian negotiation, there are multiple types and categories of negotiation processes attached to various spheres of human activities. As with any human relationship, these categories and types of human engagement, from hostile to cooperative, from close to distant require an adaptation of the tactics used for the negotiation and the calibration of the behaviors to maximize the benefit of the engagement. It is useful to understand where humanitarian negotiation fits in the larger context of negotiation activities.

For the purpose of situating the key characteristics of humanitarian negotiation, negotiation activities can be arranged in three general categories focusing on the relationship between the parties:

Humanitarian negotiations with the conflict actors are essentially relational. They aim to establish primarily a relationship between the parties as a means to facilitate an open number of agreements over a time. These agreements focus on the presence of the humanitarian organization in the area under the control of the counterpart or the access to the population and the delivery of services. While humanitarian professionals can also engage in other categories of negotiation (transactional or, at times, adversarial), they tend to be more comfortable dealing with relational negotiations, which focus on shared values and social connections.

Furthermore, humanitarian negotiations do not imply an exchange of goods or services between the parties. They consist most often of the exchange of commitments as part of the relationship between the parties to act in a particular way for the benefit of the affected population or intended beneficiaries of humanitarian assistance. For example, if an armed group agrees to the request of an organization to allow the passage of a food convoy at no cost, the direct benefit of the agreement is with a third party (here, the community receiving the food). The gain of the armed group may be elsewhere (e.g., in the perception of authority or legitimacy in the eyes of the community). The dependency of the humanitarian organization on the security guarantees of counterparts to allow them to operate in the counterpart’s territory over time is a key indicator of the relational nature of the negotiation. However, if an armed group commander is seeking a personal advantage out of the arrangement in the form of money or goods in exchange for his commitment to allow the passage, the negotiation will quickly become transactional, i.e., driven by the interest of the commander at the expense of the relationship and trust between the parties. If the commander puts pressure on the truck drivers, for example through coercion, the negotiation can turn adversarial, prompting the end of the relationship and thwarting the possibilities of future interactions.

As a result, humanitarian negotiation requires specific tools and methods to build and develop social relationships in frontline environments where adversarial encounters and the use of force are the default modes of engagement. To prepare for this dynamic, humanitarian negotiators devote more resources and time at the relational stage of the process than at the transactional stage (see Introduction | On the Planning of a Negotiation Process). If the counterpart has a monopolistic control over the access to particular goods, services, regions, or populations, building a relationship becomes the main emphasis of the humanitarian engagement. Agreements between the parties are only derivative products of the relationship. The commander of an armed group, for example, will allow the passage of a food convoy not so much because he has an interest attached to the particular passage, but because he benefits socially and politically from the connection with the specific organization or even the individual negotiator. In the absence of a trustful relationship between the parties, another convoy may be blocked on the same road, or could even be attacked.

Sorting the Types of Humanitarian Negotiation

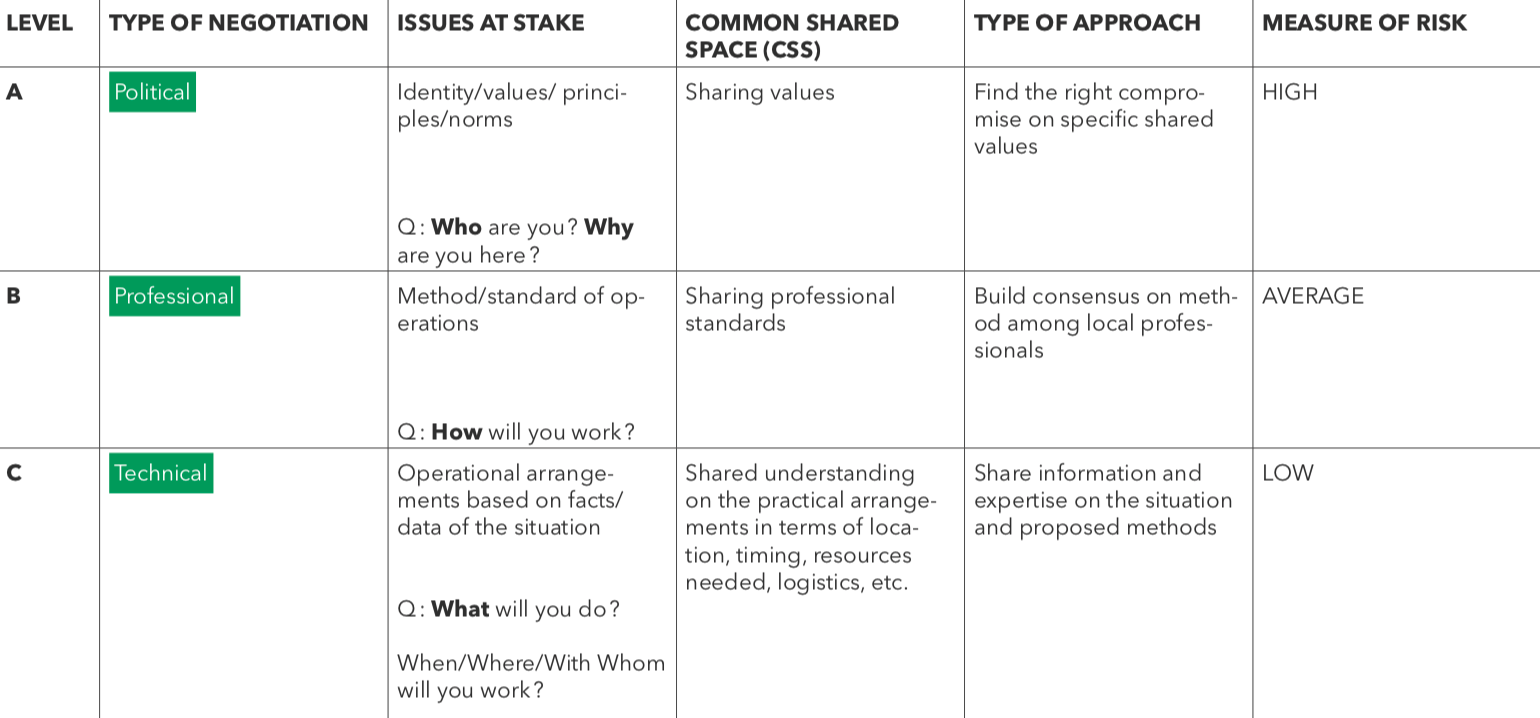

Humanitarian negotiation further divides into three types of relational negotiations focusing alternatively on the sharing of values, on building consensus on methods, or agreeing on the technical arrangements entailed in a humanitarian operation. The previous module on context analysis already identified two of these types—factual vs. normative negotiations. This module recognizes that factual negotiations are mostly technical in nature. It further inserts two subtypes of normative negotiations, the first one being political in nature, dealing with normative identity and values of the counterparts (e.g., sovereignty, religious norms, social constraints, humanitarian principles, etc.), and the second type being professional in nature, dealing with professional norms and methods recognized by specific professional circles (such as efficiency, accountability, transparency, and all applicable professional norms attached to the activities of the organization in, for example, medical or engineering terms).

A key observation of the CCHN empirical survey is that negotiators will determine their tactics differently for these three distinct types of negotiations dealing alternatively with political vs. professional vs. technical matters. All three types of negotiation aim to establish a Common Shared Space (CSS), i.e., a spectrum of possibilities for an agreement.

These three types of negotiations aim to handle specific issues that can be summarized in the following table. Each level entails a measure of risk that needs to be managed accordingly. The more political the negotiation is (i.e., value-based), the more risks are involved in terms of reputation, perception, security, or instrumentalization. A negotiation process can start at any level (A, B, or C) and then stay on the same level all along or move from level to level.

Type A: Political Negotiation

Type A Political Negotiation focuses on the identity, values, and norms of the parties.

Assuming the presentation of a standard offer of service by a humanitarian organization, the key questions of counterparts at the start of a negotiation are:

- WHO are you?

- WHY are you here?

These negotiations are considered to be “political” as they address the external character of the intervening organization or operation in the local environment as a disruption of the established political order of the host government, group, or community.

The main objective of a political negotiation on the frontline is the identification of a Common Shared Space in terms of values and minimization of the impact of the divergence of norms between the parties to allow the operation to take place with the least political risks.

A political negotiation generally is about the nature, identity, origins, and mission of an organization in the context of the cultural and social environment of the counterparts. As negotiators cannot change much about the identity, values, or norms of their organization (e.g., name of the organization, its logo, its mission, the composition of the team, etc.), there is limited flexibility for compromises. However, one may have some leverage deciding the way the organization will communicate externally in the local environment in order to minimize the visibility or footprint of the operation and the organization in the host community, mitigate political risks for the counterparts, and gain better acceptance.

Example of a political negotiation

Seeking access to war widows in a conservative religious environment to survey food insecurity

The monitoring of data on food security is a technical matter that should not disturb the political order of any country. However, access to war widows may represent a very sensitive issue in conservative religious countries where women tend to be quite isolated or even secluded in their domestic environment. Widows who have lost their spouse as well as contact with other male intermediaries with relief organizations may be particularly vulnerable to food and health insecurity.

Accessing them may raise serious social and cultural concerns by the leaders of the community regarding the honor of the family and of the community, especially if this access is performed by foreigners. Contact with male monitors, foreign or local, may be forbidden by local social norms. Negotiating access to war widows may turn out to be a political negotiation in terms of seeking ways to address religious concerns while respecting the principle of impartiality, even before handling the technical aspects of the monitoring.

The main recognized tactic of a political negotiation is to find the right compromise with the counterparts on the profile of the organization and the impact of its identity and values within the community so as to maximize the benefit of its presence and activities and minimize the political costs associated with the mission of the organization (e.g., operate in partnership with a local NGO, be accompanied by a local representative, hire local staff, withdraw logos, etc.). A prepared narrative explaining relevant aspects of the mandate and mission of the organization in the words of the counterpart will help to develop a proper understanding of the organization with the counterpart. It should be underscored that “cutting deals” on identity (e.g., hiding the organization’s logo), norms (e.g., refraining from mentioning human rights or international humanitarian law), or values (disregarding peripheral issues such as trafficking or underage marriage in the community) may have severe consequences for the integrity and reputation of the organization. These negotiations are a source of considerable risks for the organization. The management and leadership should be consulted as the frontline negotiator considers necessary compromises within clear “red lines” (see 3 | Module B: Institutional Policies and Red Lines).

A political negotiator is someone who can understand well the political situation of the counterparts and the implications of potential deals in order to find appropriate and practical arrangements to address legitimate concerns of all those involved.

For these reasons, humanitarian organizations should be attentive to when a situation calls for sending a qualified “political” negotiator to discuss the profile of the organization. Professional or technical members of a team may not be able or willing to work out necessary arrangements on the visibility or positioning of the organization, or, conversely, may go too far in compromising the values of the organization in view of the needs of the population that threaten the image and reputation of the organization.

One should be aware that “political negotiation” does not necessarily mean “high level” negotiation. All the levels of management should expect to be engaged at some point in political negotiation, i.e., dealing with the value and identity of the organization, starting with the local staff. Political negotiation may take place at the national or local level, or even at a checkpoint—in fact, everywhere a counterpart may ask the political questions: “Who are you? Why are you here?” These questions may be satisfied by a short and acceptable explanation if the counterpart has little to lose in allowing access, or, alternatively, may be the start of a lengthy and sensitive process if the presence of the organization disturbs the political order of the host in terms of value in the local context.

Although experience in political negotiation is a definite asset, the seniority of the representative may represent a liability in some situations. One may want to mitigate the reputational risks of a political negotiation by sending a person with a lower level of responsibility to a political negotiation in order to avoid unnecessary exposure if the proposed arrangement carries some risks to the organization.

Type B: Professional Negotiation

Type B Professional Negotiation focuses on the methods and standards of an organization’s operation.

The key question at the start of a professional negotiation is:

- HOW do you intend to operate in the country/region/location?

The main objective of a professional negotiation is the identification of shared operating standards and minimization of the impact of the divergent professional norms between the humanitarian organization and the professionals operating in the context.

In a professional negotiation, the negotiator is aiming to build consensus with and among the host professionals regarding the method and standards that will be applied to the operation. The approach is to mobilize the support and guidance of this professional community in order to reach consensus in terms of method and accountability. If the professional authority or circles are weak or absent, the negotiation will quickly turn technical (see Type C, below). Professional negotiation is an important buffer between political and technical negotiations as it allows for avoiding falling into political negotiation on value and norms each time there is a blockage at the technical level. Professional negotiation allows for the maintenance of a professional relationship with the local nurse, district health director, head of the hospital, etc., to discuss the methods of the operation with professional counterparts who can appreciate the proposed choices and plans. Professional negotiations will go on until one of the counterparts believes that the discussion has become too technical and specific (i.e., to be dealt with by the technical authorities), or, conversely, too political by engaging value and identity issues (i.e., to be dealt with by political authorities).

As with political negotiation, the operational standards and methods of the organization may be misunderstood (e.g., vaccination protocols, assessment and monitoring methods, accounting and financial standards, etc.) and entails risks if these methods are not in line with local practices. As compared to political negotiation, the point is not about finding the right compromise, which may be unsuitable to the professional character of the organization, but rather building a new consensus around the professional norms of the organization or finding ways to accommodate both the local and institutional norms.

Example of a professional negotiation

The provision of surgical kits to local physicians operating in remote locations

Medical Help International (MHI) plans to provide surgical kits to local physicians treating displaced persons suffering from crocodile bites and other serious injuries in the forest of Country A. These professional kits contain surgical tools that require detailed training and specific skills to limit the health risks of the procedures for the patients.

Several of the local physicians have had only limited training in surgery since very few anesthetics are available in these remote locations. While MHI is ready to send some qualified surgeons to the affected area, the demand for proper surgical training surpasses the capacity of MHI. MHI considers it unethical to provide surgical kits to physicians who have not been properly trained to undertake surgical interventions. It is considering suspending its program in Country A as it represents a major professional and reputational risk to the medical organization.

The National Health Authority of Country A does not require specialized training for general surgical interventions in remote areas due to the lack of professional capabilities and the scarcity of anesthetics. It expects MHI to distribute the surgical kits urgently needed by the local physicians in view of the skyrocketing morbidity and mortality in the region due to a surge of displaced persons wounded by crocodile attacks.

In the example described above, a medical professional aware of the importance of the ethical and professional standards involved could work with the National Health Authority to determine: