To support fighting COVID-19 in the Donbass, ICRC provides a stock of personal protective equipment and materials to dispose of hazardous substances to a team of rescuers. (Photo: Yovgen Nosenko/ICRC)

Introduction

For the first time in four generations, a huge crisis is striking globally. The current calamity and its rapid spread is generating huge disruption in our societies and is shaking our belief in society’s ability to protect the population. It is also opening the door to serious questions about our current and future ability to outwit such massive phenomena. It may be time to reflect on the true nature of crises and their particular features and why we seem to be taken aback by their occurrence. To paraphrase the French catastrophist Patrick Lagadec[1], we have entered “the continent of the unexpected”.

A crisis, not an emergency

A crisis is a specific, unexpected (or unpredictable), and non-routine event or series of events that create a high level of uncertainty and a threat or perceived threat to an organization’s high-priority goals. A crisis is a unique phenomenon that can neither be rehearsed nor completely anticipated. It is not just another emergency. An emergency takes place in an environment that is known and can be managed within the existing framework and understanding. Whereas a crisis is characterized by discontinuity, uncertainty, and complexity.

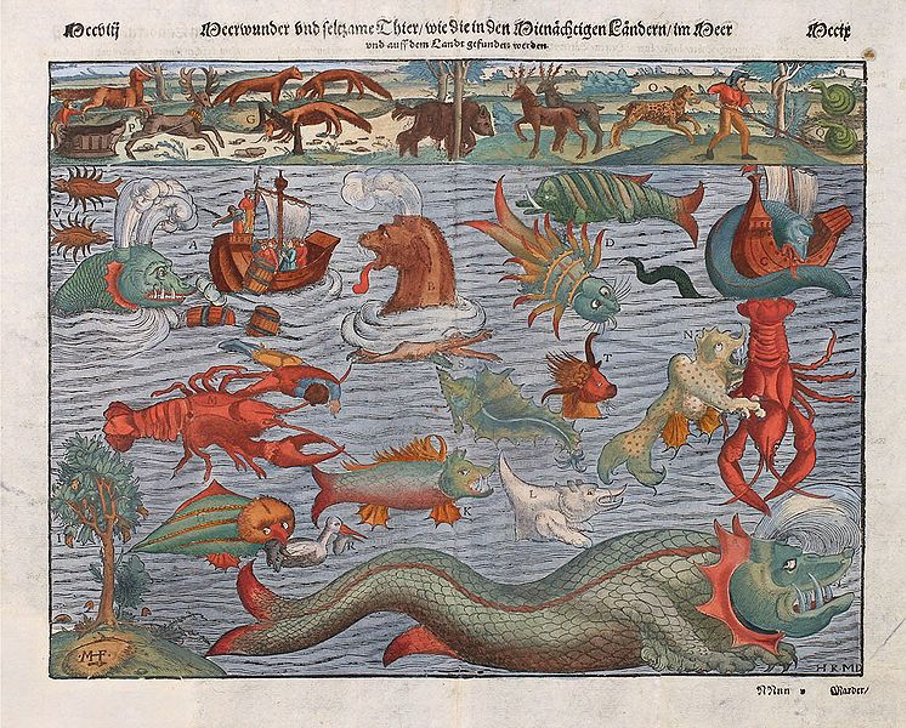

Put more simply: it is a jump into the unknown. Hic sunt dracones[1] as medieval cartographers would label unchartered waters.

In a complex environment (a network of components which give rise to complex collective behaviour), a true crisis is in fact a succession or combination of crises which interact with each other and generate a vast array of predictable as well as unpredictable effects and new cascading phenomena that are difficult or impossible to anticipate[2].

The Great Plague of 1346 -1353 brought considerable changes in Western societies, such as to the role of religion and structure of political institutions. And COVID 19 may transform the humanitarian ethos as we know it.

COVID-19: A Networked Crisis

COVID-19 is typically a networked crisis. The virus that led to the disease COVID-9 was only the beginning that set off the chain of events and phenomena. The viral infection became a medical crisis, then a public health crisis, rapidly leading to an economic and financial crisis, political and leadership confusion, and is now accompanied by growing social stresses and worries about the provision of basic necessities. And these interact in surprising ways.

As Jacques Attali[3] clearly indicates, such catastrophes tend to call into question systems of belief and the nature of control and the regime of authority. Such mega crises may not only challenge existing societal bulwarks but could be also a game-changer both on the national and international scenes.

So far, States and their institutions in the Western world, as well as in the so-called global South, have held up quite well. The international order is (not yet) crumbling. However, we should not underestimate the possible transformative effects initiated by the COVID-19 crisis.

“Here be dragons” means dangerous or unexplored territories, in imitation of a medieval practice of putting illustrations of dragons, sea monsters, and other mythological creatures on uncharted areas of maps where potential dangers were thought to exist. (Wikipedia)

Security Spill Over – Recent Experiences

In addition to structural transformation, such a mega-crisis may also generate unpredictable collective human behaviour that may create new political, social conditions, or humanitarian challenges. A peak in criminal behaviour or collective violence, due to the authorities’ inability to care for their own population, would challenge the resilience of already weak institutions and their functioning. And this would, in turn, lead to additional security issues. Trust in the system and its representatives proved critical for maintaining the social fabric during the Great Influenza of 1918[4]. Can we expect the same level of resilience in the interconnected world of 2020?

We have seen in the recent past that the development of the Ebola crisis (2014) in West Africa was clearly linked to the robustness (or lack thereof) of each nation-state. In Liberia, largely a

failed state at that time, the initial health issue quickly became a security problem requiring intervention from international forces. Whereas in Sierra Leone, with stronger state structures, the crisis did not result in a situation of violent unrest, although the Ebola crisis inflicted significant damages on other life-saving programs such as the anti-malaria programs.

In Sicily, some observers have already reported signs of unrest, and police had to be called to a supermarket, where people stole food to feed themselves as patience turned to desperation[1]. There are already some signs that the current crisis is generating xenophobic campaigns against foreign organizations in South Sudan or RDC.

Bounded Rationality – The Natural State of the Negotiator’s Ecosystem

Crisis situations inevitably create the feeling that humanitarian response is not based on pre-established routine, secure data, proper deliberation, and cartesian logic. These are part of the response, but such situations by nature also call for gut instincts, guesswork and conjecture. Crisis management relies deeply on our capacity to see problems from the right angle, with the appropriate level of understanding and to respond rapidly. In other words, it depends on our capacity to produce real-time actionable intelligence about what is going on.

Decision-makers will, therefore, have to improvise solutions in a very complex environment where they do not have control over a range of parameters or data (such as the international environment, cross border phenomena, or scientific facts).

Necessary Tinkering

Some critics are complaining about the absence of a full-fledged response plan. Where is the comprehensive and definitive strategy? Fortunately, there is no such comprehensive plan. Ready-made solutions would not work in that case. Rigid, fixed, and untargeted procedures may even make problems worse. Appropriate responses are particularly difficult to design because the phenomenon is iterative, fluid, and quite unpredictable. The question is not to think out-of-the-box, simply because there is no box anymore.

Unfortunately, planning which could absorb the shock is also non-existent. Let us take this as a given and let us move on.

Yet, decision-makers must invent solutions in a very complex environment where they do not have full control over many parameters and where they will not get reliable data. Responders must, therefore, use opportunistic and tinkering methods instead of building large and presumably coordinated systems. And they must make sure that these measures do not produce unintended and negative effects. They will also have to stand up against the sweeping strategies cooked up by their donors.

The Humanitarian Negotiator’s Role in Times of Crisis

Is there a specific role for experienced negotiators in times of crisis? The current situation will certainly exacerbate existing humanitarian issues and may trigger additional problems such as rapid reductions in funding, restriction of access, increased security measures, or new forms of collective violence or exclusion.

Will the so-called humanitarian order be boosted by a new form of international solidarity or be further constrained by a desire for stronger national sovereignty and selfish national interests? Nobody knows at this stage, but we can safely assume that the post-crisis phase will bring further humanitarian shortcomings and impose additional constraints. The time is not ripe for messianic multilateralism. Instead, frontline negotiators will have to step up and to tackle new problems and issues head-on.

Nowadays it is considered very fashionable and intellectually safe playing the Cassandra and forecasting profound, massive changes or even announcing a doomsday era. Let us put it more humbly this way.

As far as we can safely predict, humanitarian actors will have to cope with the fact that the humanitarian system will be less able to deliver or to protect and that organizations will be facing new types of humanitarian consequences. Acceptance or trust will not improve from three months of limited operational capacity. Humanitarian operators will be under pressure from all sides. In such difficult circumstances, their skills such as empathy, adaptability, the inclusion of meaningful actors, innovative solutions, and trust-building will be key to successfully facing the enormous challenges ahead and containing further crises.

Humanitarian negotiators are not free agents who can swiftly switch boats if there is no perspective of short-term results. They are the public face of organizations that cannot shirk their real or perceived responsibilities and must continue to operate on behalf of impacted populations. These populations may discover that, after having been neglected or abandoned for months, they can expect to have more of a say about the way humanitarian action is designed and implemented.

The good news is that humanitarian negotiators are probably better equipped to embrace crises than anyone else because they have to deal every day with system stressors, surprises, and setbacks. They could play a decisive role in advising the log frame, strategic planning, and excel sheet managers who have been paralyzing humanitarian response for years under the guise of professionalism. The new humanitarian frontline will not be only around facts and evidence but rather around norms, perception of justice, and grievances. Negotiators should be ready for that battle.

[1] Lagadec, Patrick, le continent des imprévus, Manitoba, Belles Lettres, 2016.

[2] Declaration of Senator Harry Reid, on September 18, 2009 in the midst of the economic debacle: « No one knows what to do. We are in a new territory here. This is a new game. » (‘Here be dragons.’)

[3] Nobody could predict that banking information could not be exchanged across borders and therefore preventing French employees having their jobs in Switzerland to work from home.

[4] See Jacques Attali blog post : Que naîtra-t-il ? 19.3.2020

[5] Barry, John M. (2005), The great influenza: the epic story of the deadliest plague in history (New York: Penguin Books) 546 p.

[6] Discomfort and malaise are growing and we are recording worrying reports of protest and anger that are being exploited by criminals who want to destabilize the system,” declaration from the Mayor of Palermo, Sky News, 28.3.2020

Pascal Daudin is a co-Founder of Anthropos Deep Security. Since 2011 and until recently, he was Senior Policy Adviser on humanitarian action-related matters at the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) who has been actively involved in the CCHN activities. After a short career as a freelance journalist, he joined the ICRC in 1985 and served in more than twenty different conflict situations including Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, Kuwait, Caucasus, and Central Asia, holding positions of Line Manager and Protection Expert as well as managing institutional reform. Between 2003 and 2007 he worked as Senior Analyst and Deputy Head of a counter-terrorism unit attached to the Swiss Ministry of Defence. In 2007, he was appointed Global Safety and Security Director for CARE International’s operations and institutional policy.