Humanitarian professionals often engage with military counterparts out of necessity, as they must work in complex and conflict-affected environments.

Effective negotiation and collaboration between these two sectors can help ensure humanitarian assistance reaches those in need while respecting humanitarian principles and protecting the safety and independence of humanitarian workers.

However, working relationships between humanitarians and military counterparts aren’t always straightforward. Both arms carriers and humanitarians believe that they are well understood by the other, but the opposite is generally true.

Militaries have little idea about humanitarians and their work, and humanitarians usually lack an understanding of what makes militaries tick, which can make negotiating with them feel intimidating.

Stephen Kilpatrick, advisor on relations with arms carriers for the International Committee of the Red Cross and former British soldier, shares six practical tips for humanitarians on negotiating with the military.

1. Use your “elevator pitch”

When you meet a military counterpart for the first time, make your first encounter count.

Use your “elevator pitch” to briefly explain who you are, who you work for and why you are there. Don’t race through the political level of the negotiation!

If you go with a team, make proper introductions. Offer some details about their background to explain to your counterpart who is in the room.

Often, military commanders will meet with many different organisations. Being clear and concise about yours will help them untangle it from others.

Remember, you don’t get a second chance to make a good first impression!

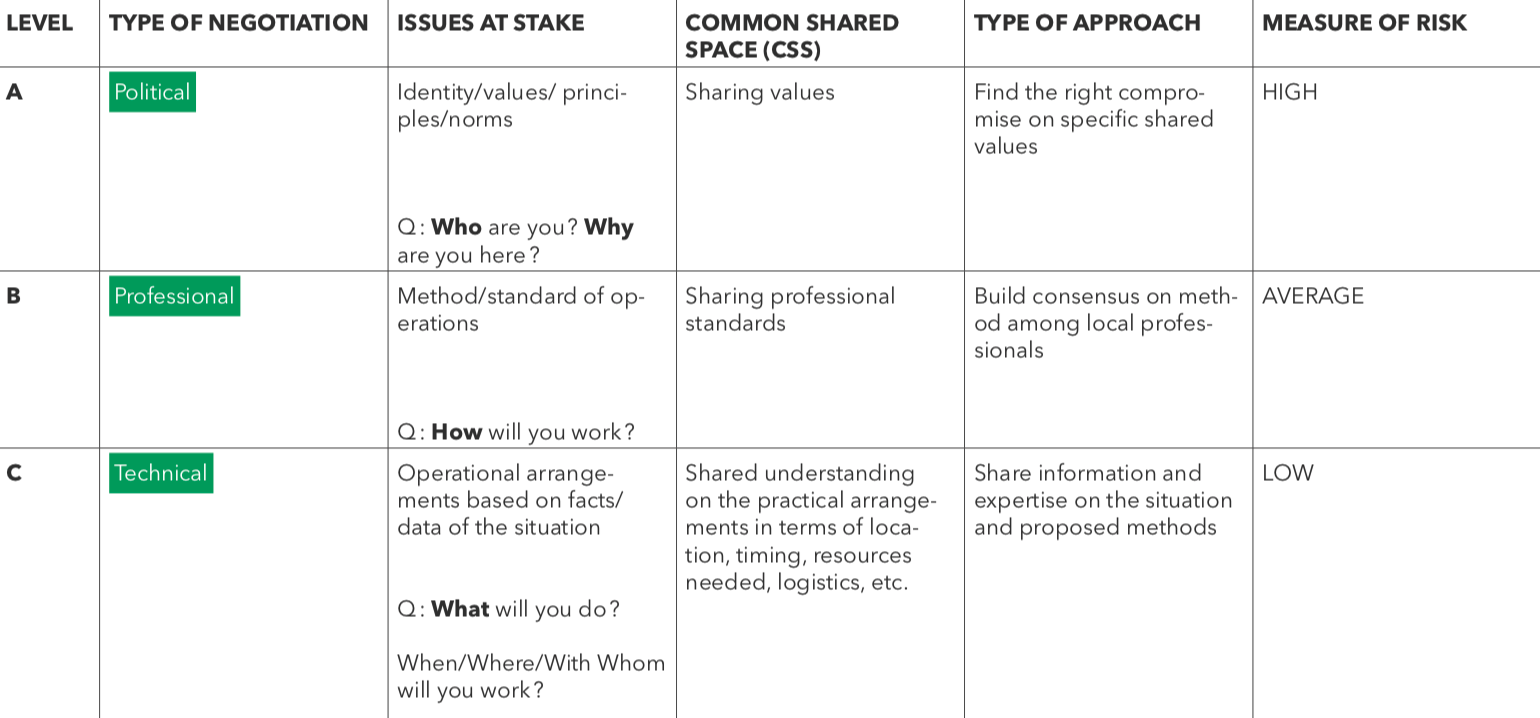

The typology of a negotiation is one of the tools used to structure a humanitarian negotiation. For more information, read the CCHN Field Manual on Frontline Humanitarian Negotiation.

2. Expect your counterpart to be on the front foot

Force projection, combat power and offensive spirit are key elements militaries use to achieve their goals, like overcoming an adversary.

This can easily translate into their attitude towards negotiations. Few militaries have negotiation doctrines and instead tend to approach conversations with humanitarians on the front foot. Be aware that some military commanders will use “offensive spirit” as the basis for their negotiation.

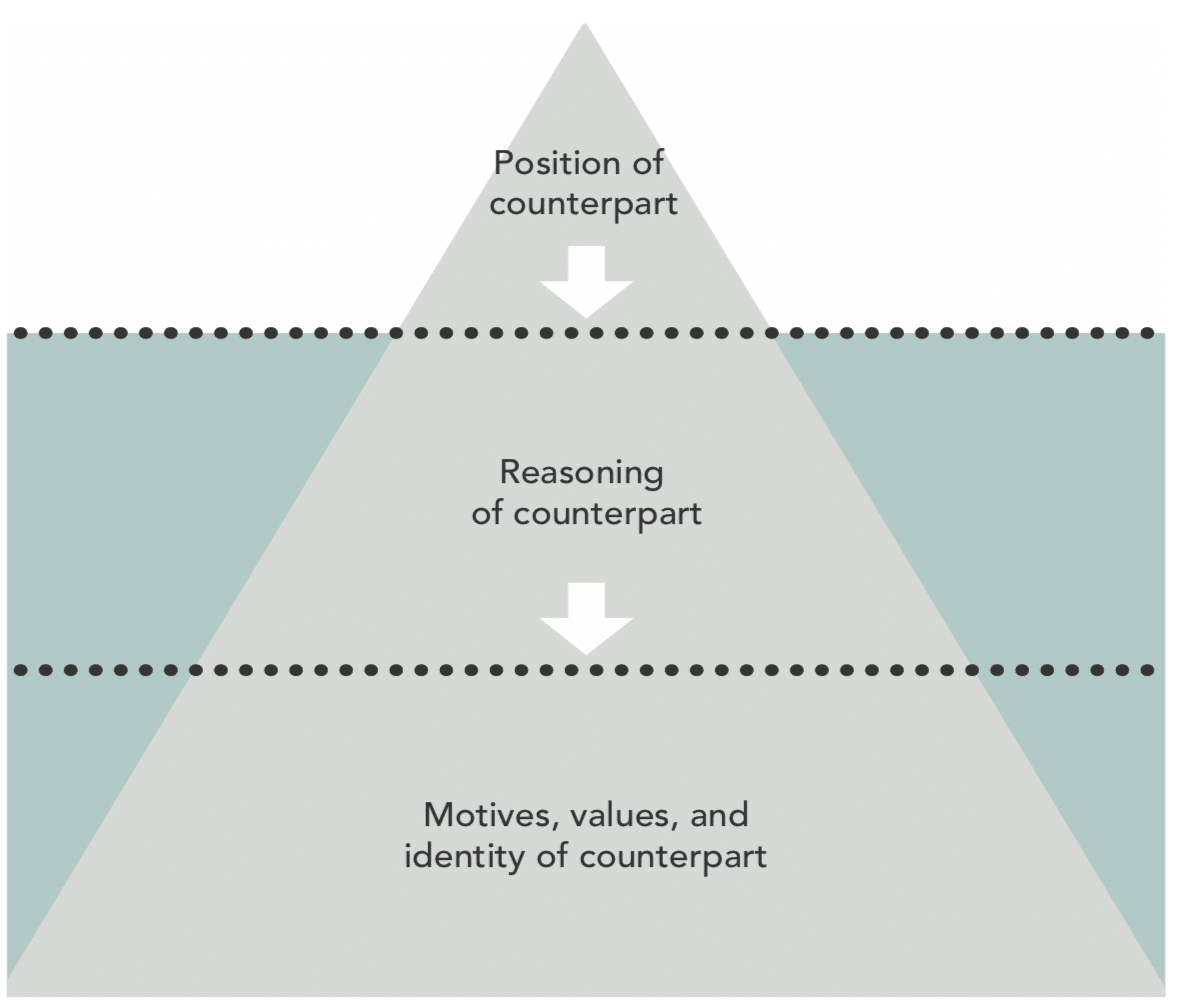

For best effect, use tools like the negotiation “iceberg”, the typology of negotiations or a stakeholder mapping. They will help you understand and familiarise yourself with your counterpart and prepare your negotiation.

Whenever you can, rehearse what you will say. It will help you to feel less intimidated when you face a powerful general surrounded by their staff. If possible, you can also suggest a one-on-one conversation.

3. Anticipate the security argument

Security is a principle of war, and a baseline from which militaries conduct all other activities.

Military commanders will often use “security” as their trump card in negotiations. If you want to work in an area under their responsibility, militaries will likely use this argument to limit your organisation’s ability to operate in a certain area or deny you access to it.

Since security is a powerful argument, anticipate and respect it. For militaries, security is paramount and dismissing it won’t help your negotiation.

For this reason, you should prepare a counter argument, and another counterargument… Militaries might feel they are responsible for your security, but you might argue that being present in the area and seen by all parties to the conflict is the best way to guarantee your safety. In other words, work out what your trump cards could be.

Last, but not least, avoid using a computer to take notes when talking to a military counterpart. An electronic device could jeopardise the meeting’s confidentiality because your counterpart could suspect you are recording the conversation. Instead, put them at ease and use an old-fashioned notebook.

4. Understand the hierarchy

Militaries are hugely hierarchical. Understanding their rank and commands means understanding who you’re talking to.

Addressing your counterpart with the correct rank shows you have done your research and take the meeting seriously. In other words, it shows professionalism.

Equally, being familiar with insignias and medals can help you deduce who you are speaking with.

For instance, you can infer the seniority of your counterpart by the location of their badge on their uniform. If they wear it on their arm, they’re low ranking. If they wear it on their shoulder or chest, it means they hold a position of authority within the military.

Another good idea is to try to understand under which “culture of command” they operate. Some militaries allow responsibility to go down to the lower levels of command; this is a “mission” culture of command. Conversely, if you’re talking to a colonel in a military with “directive” command, you won’t get far because control is vested only in very senior roles.

5. Find out their needs (and how you can meet them)

Identifying a military’s needs and how you can meet them can help your counterpart understand your organisation’s value and gain their acceptance.

A few years back, a humanitarian team met with a general in Myanmar. He was very unconvinced about the organisation’s work in the region; however, a team member identified that his army was interested in the organisation’s prosthetic programme because a lot of soldiers had lost limbs to landmines.

Once the humanitarian team brought their prosthetic specialist to the meeting, the general understood the organisation’s added value. The organisation established a positive relationship with the army and was able to operate in the region safely.

This is a good example of taking the time to understand your counterpart using the negotiation “iceberg”. What are their values, motives, and reasoning? How does this support their position? What needs do they have and how can you help them meet them?

The negotiation iceberg is one of the tools used to structure a humanitarian negotiation. For more information, read the CCHN Field Manual on Frontline Humanitarian Negotiation.

6. Figure out who is pulling the strings

It’s not what you know… it’s who you know.

There are times when negotiations get stuck (or fail), and all your negotiation expertise can’t make any difference.

Why?

Because you’re talking to the wrong person.

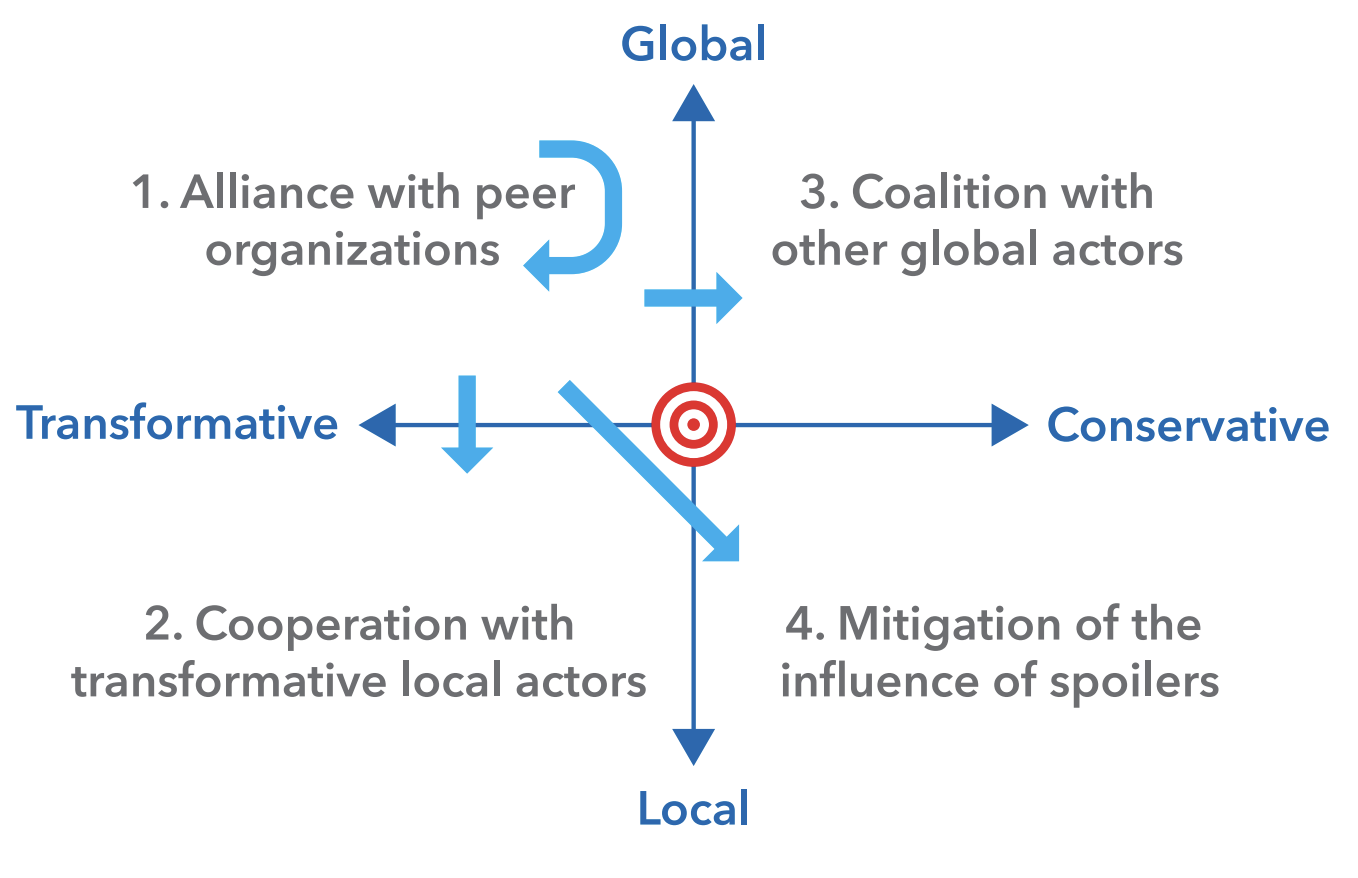

Conducting a stakeholder mapping can help you identify who might be blocking (or “spoiling”) your negotiation and who could influence their position. If you can figure out who is pulling the strings, you might be able to unblock your negotiation deadlock.

The stakeholder mapping is one of the tools used to structure a humanitarian negotiation. For more information, read the CCHN Field Manual on Frontline Humanitarian Negotiation.

Remember...

When negotiating with military counterparts:

- Do not assume military officers understand humanitarian organisations. Always open with a clear explanation and introduction.

- Expect them to be on the front foot. Most militaries don’t have a negotiation doctrine.

- Acknowledge security concerns, but have a counter-argument.

- Try to understand ranks, appointments and culture of command.

- Understand their needs and find ways you can meet them.

- In case of a negotiation deadlock, figure out who is pulling the strings.