Resources

Field Manual

Introduction

The objective of this section is to provide a framework for the colleagues of the frontline negotiator to assist and support the development of the negotiation strategies and tactics.

Frontline negotiation is understood across the humanitarian community as a relational undertaking involving the humanitarian negotiator and his/her counterpart(s) in a search for common grounds to ensure the provision of essential assistance and protection to populations in need. The relational character of this activity is seen by practitioners as a core element in building trust between individuals and organizations in situations of armed conflict and violence. Building on their personal connection, negotiators on both sides are able to ascertain their shared interests to drive the negotiation process forward.

One side effect of this personalization of the relationship is that decisions on the orientation of the negotiation process are often made primarily by those negotiators involved at a personal level. Humanitarian negotiations can easily turn into private dealings if the process is not integrated into a professional and critical endeavour, as the scope of interests and the stakes at play are usually much larger and more far-reaching than the ones envisaged by the individuals in their relationships. The larger picture may have considerable implications in terms of the lives and dignity of thousands of people, as well as the reputation, safety, and security of a whole organization.

Humanitarian negotiations are team-based, comprising the frontline negotiator who leads the engagement with the counterpart, the negotiation support team who assist in the critical reflection on the orientation of the process, and the mandator who frames the process into the institutional policies and values.

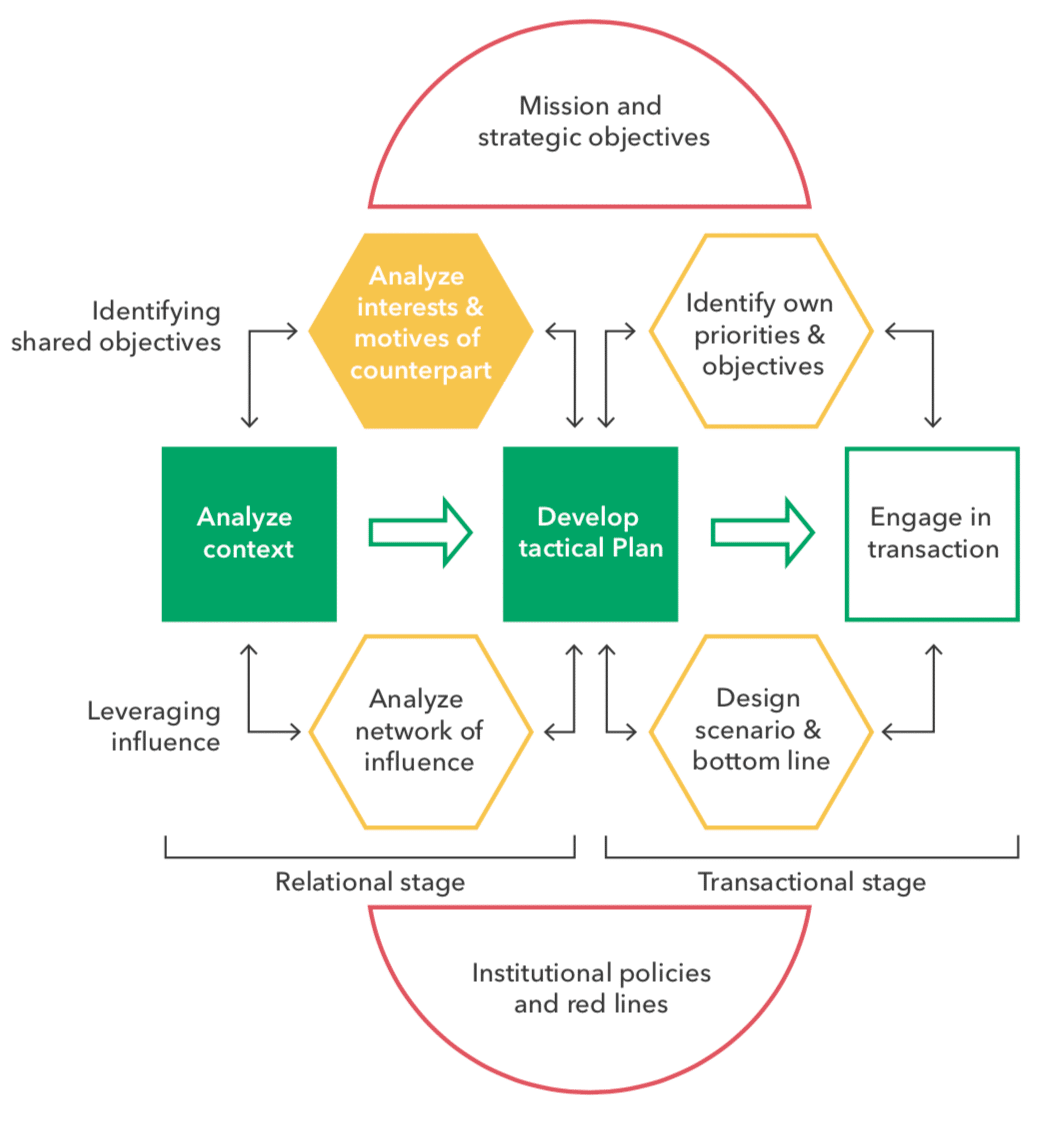

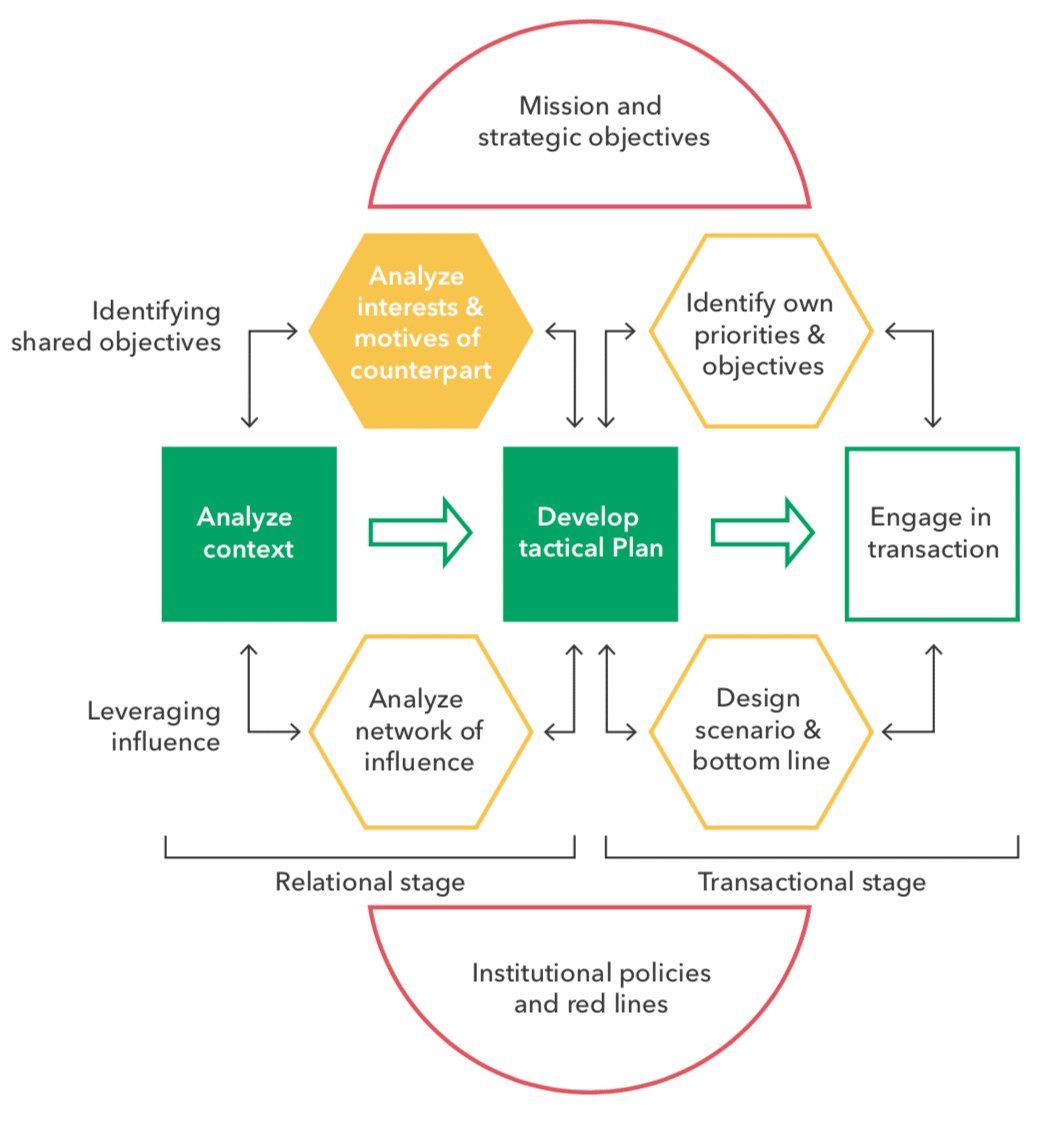

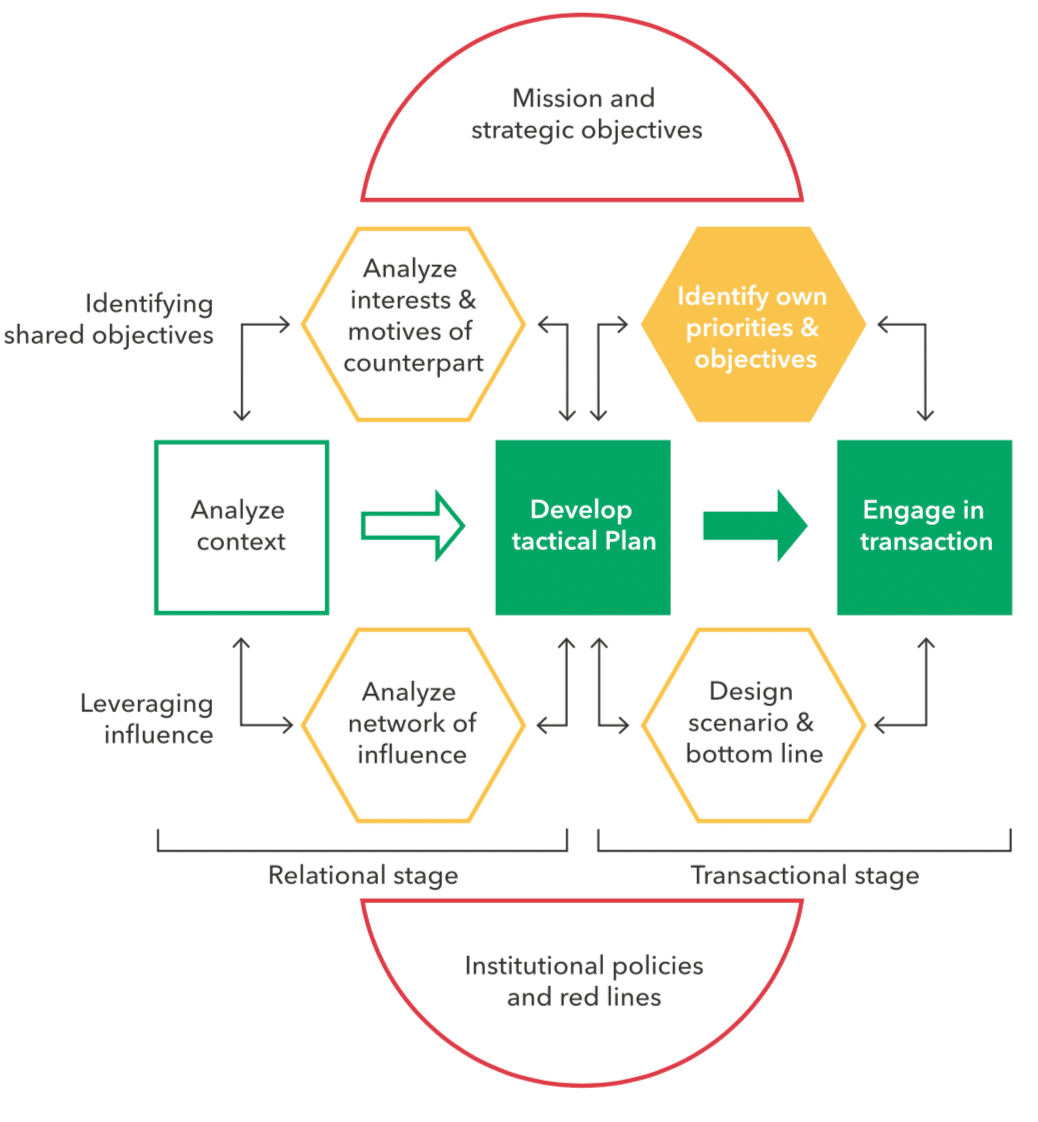

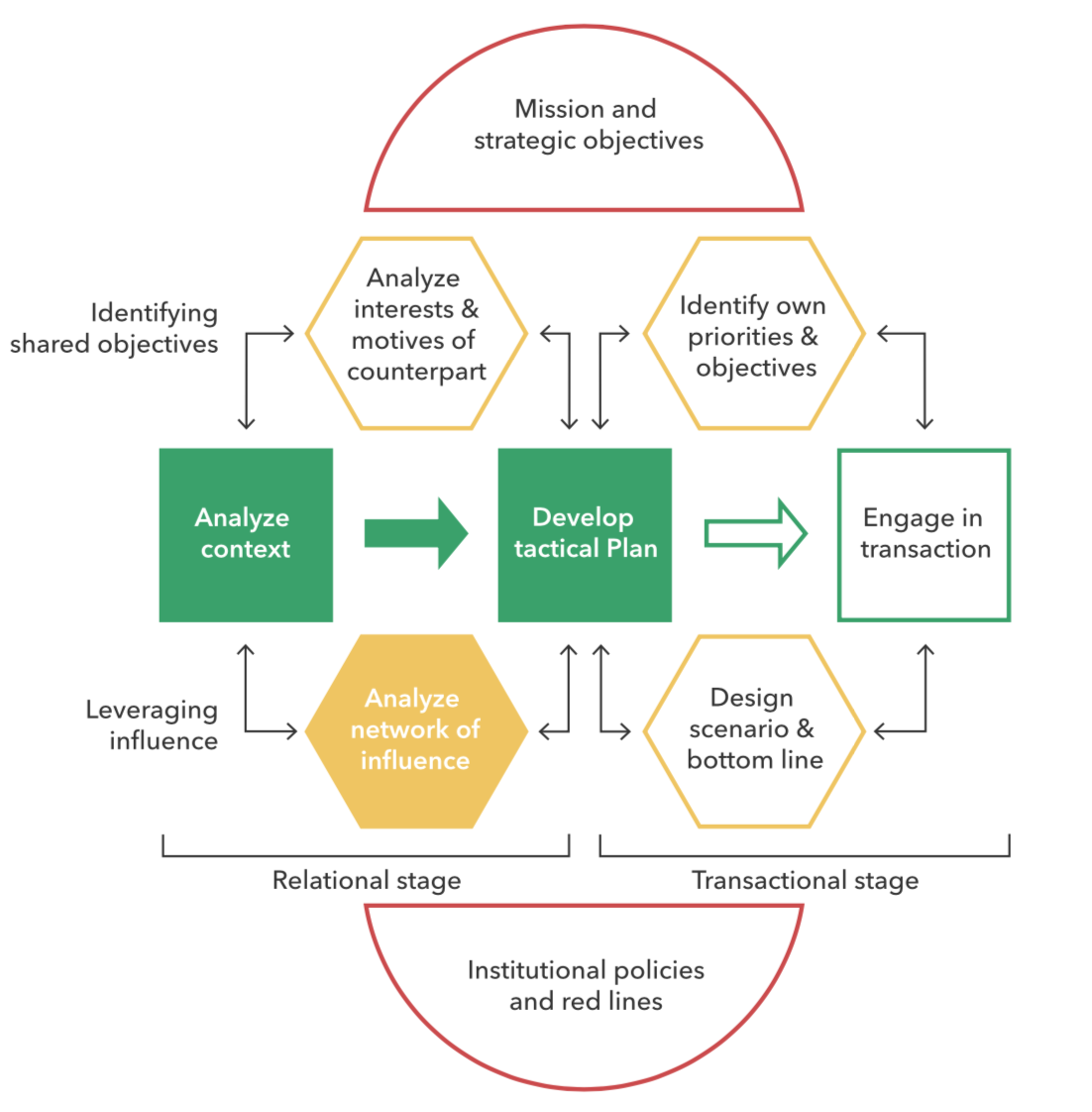

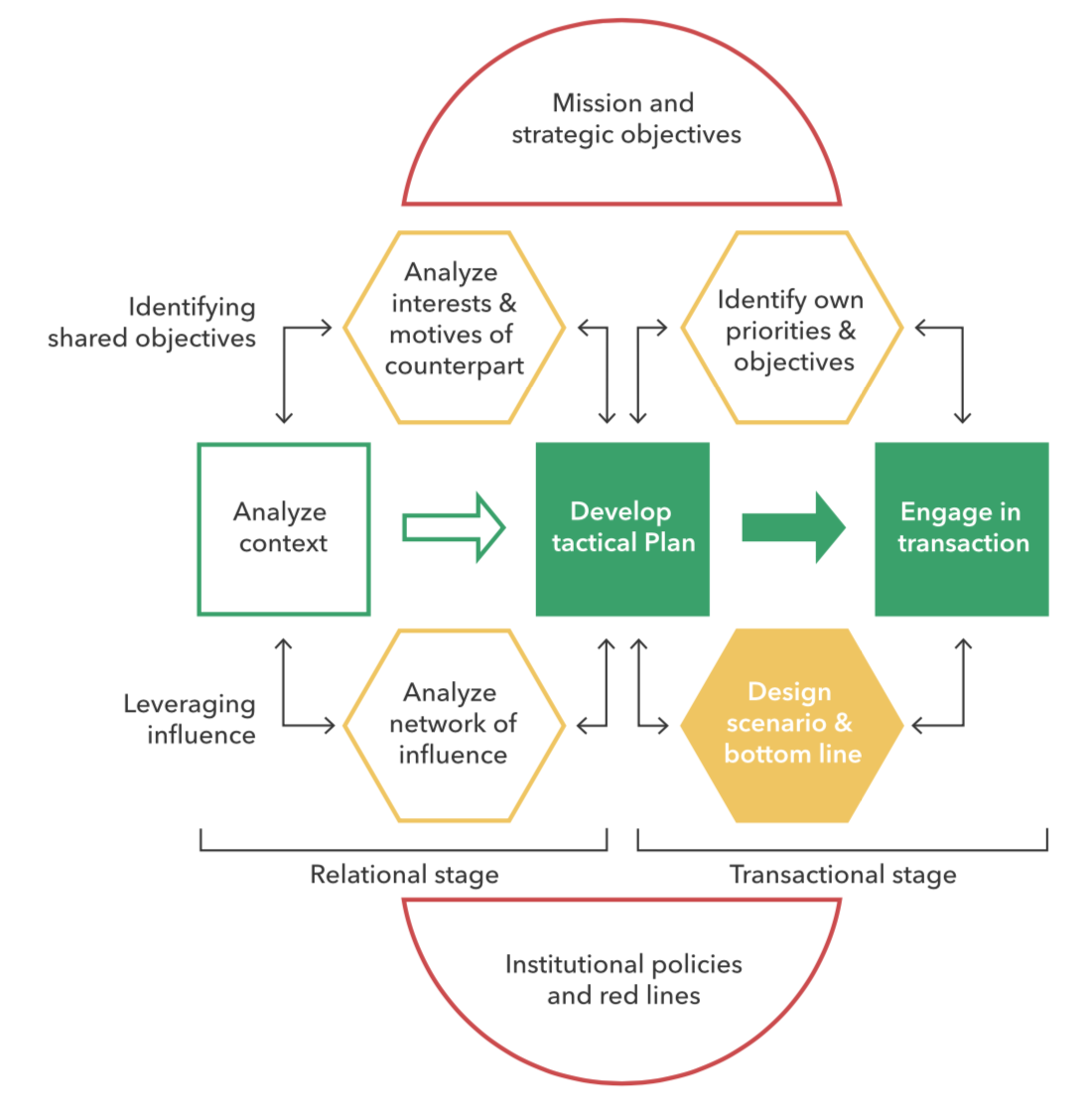

The team-effort model is an effective way for solo practitioners to maintain their autonomy as frontline negotiators while making a responsible and professional decision to open a critical collaborative space around them in the planning process of the negotiation. The deliberation within the support team aims to ensure the maintenance of the required critical space to define and regularly review the objectives of the negotiation process and inform the design of the tactical plan (see Figure 1).

These deliberations primarily engage the humanitarian negotiator who is responsible for driving the negotiation process (see 1 | The Frontline Negotiator) and team members and peers who are closed to him/her. The due diligence process among professionals involves sharing their views on critical orientations where emotion, frustration, and stress can play a detrimental role. This practice also provides an assurance to the mandator—the hierarchy of the organization—that tactical choices are made deliberately, i.e., with consideration of different options and perspectives.

This section will examine successively a proposed set of tools to:

- Analyze the position, reasoning, and values of the counterpart regarding the object of the negotiation;

- Identify specific priorities and objectives of the negotiation process;

- Design scenarios, bottom lines, and red lines to frame the negotiation process; and

- Assess the network of actors who may influence the position of the counterparts.

These practical tools should serve as background elements to guide internal discussions between the frontline negotiators and the negotiation team.

Introduction

The purpose of this segment is to analyze the underlining reasoning and motives of the counterpart that may explain the position of the parties in a negotiation process. This analysis builds on the assessment of the political, social, and humanitarian context.

The analysis of the position of the counterpart(s), as well as the understandings and perceptions of the constituency of the counterparts, will inform the development of the position of the humanitarian organization and facilitate the design of the tactical plan by its negotiation team (see 2 | Module B: Identifying Your Own Priorities and Objectives). They will help to identify points of convergence and divergence between the positions of the parties related to a specific negotiation. This assessment will further inform the type of negotiation to be envisaged—whether political, professional, or technical in nature—and the selection of the skills required—conciliation skills, consensus-building skills, or specific technical abilities (see 1 | Module B: Tactical Plan).

Tool 9: Analyzing the position of the counterpart

A negotiation process entails from the outset various points of convergence and divergence between the parties—some may be explicit, others may be more implicit. To prepare for the negotiation process, the humanitarian negotiator should draw his/her tactical plan on a solid understanding of the position and perspective of the counterpart on the given issue and in a given context. This preliminary assessment aims to understand the framing of the position of the counterpart in a holistic and non-judgmental manner. The goal is to avoid focusing too early on the points of divergence and try to elucidate the counterpart’s inner reasoning and inner motives, especially in terms of loss, fear, and grievances, as these elements are major drivers of positions in frontline negotiations.

Based on the information gathered in the course of the context analysis, the main questions are therefore:

The starting position of a counterpart is generally based on a logical reasoning that reflects its tactical interests and a set of intrinsic values and norms that are at the core of its identity. The discussions at the negotiation table tend to evolve between these levels.

Here are some examples to illustrate the levels of the discussion.

What does the counterpart want?

- In response to a request from Health for All (HfA), an international NGO, to open a clinic in Country A, the Minister of Health communicated the Ministry’s starting position that HfA needs to obtain a license from it to operate the clinic.

How did the counterpart get to this position?

– Based mostly on logical reasoning (a fortiori):

- The Minister of Health requires HfA to obtain a license from the Ministry before it starts operating in the country, as HfA would do in its country of origin.

– Based mostly on legal/professional reasoning:

- A license to operate in Country A is required under national law applicable to all medical NGOs. The reason for the license is to ensure the respect of professional medical standards in Country A. Failure to comply may generate legal liabilities for HfA and its representatives.

Why does the counterpart take such a position?

– Based mostly on value-driven motives:

- The Minister of Health orders the representatives of Health for All to respect the national sovereignty of Country A by subjecting all international NGOs to the law of the land. Failure to comply with licensing requirements will be considered an unacceptable intrusion by HfA into the internal affairs of Country A.

Depending on the assessment of the roots of the position, the negotiation team will consider driving the negotiation as a technical, professional, or political process, which will dictate the type of negotiation to be conducted and tactics to be used (see 1 | Tool 4: Determining the Typology of a Humanitarian Negotiation). The negotiation team may also consider politicizing or depoliticizing the negotiation process depending on the strengths and weaknesses of the organization’s own position and influence at each of these levels.

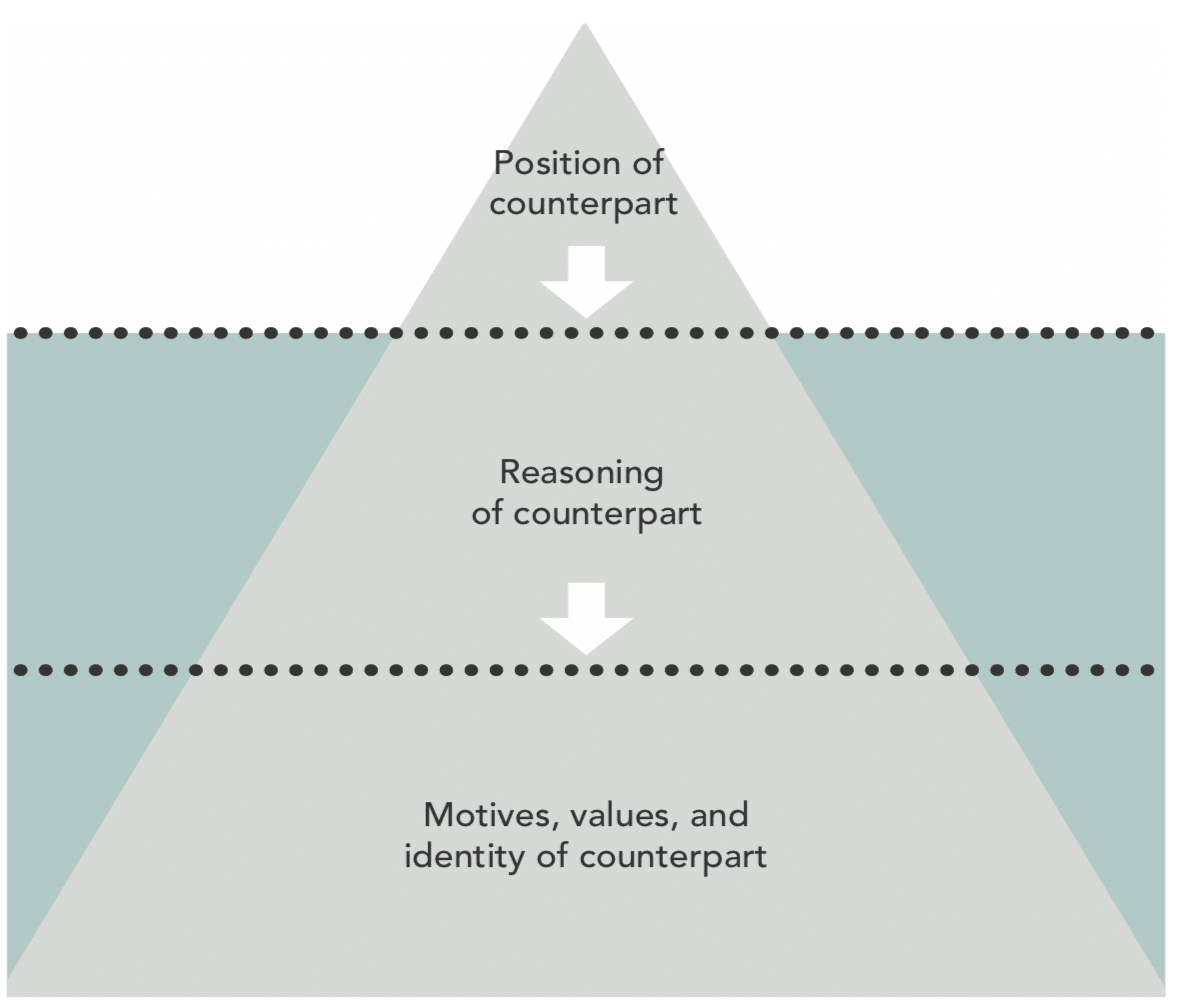

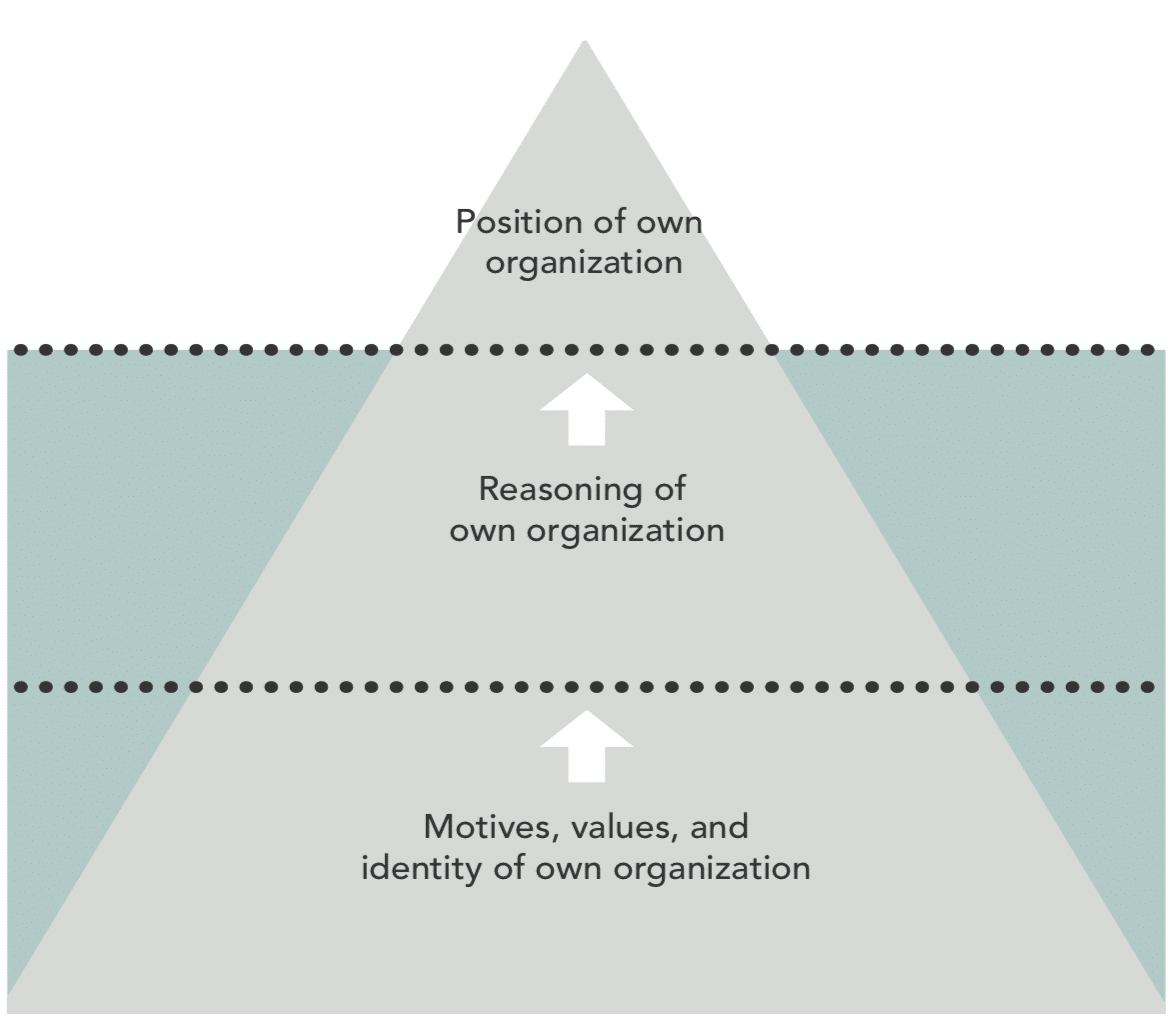

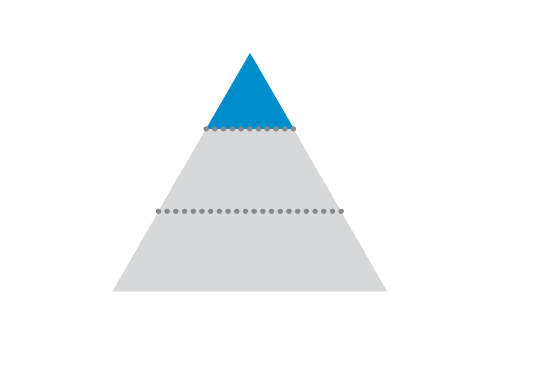

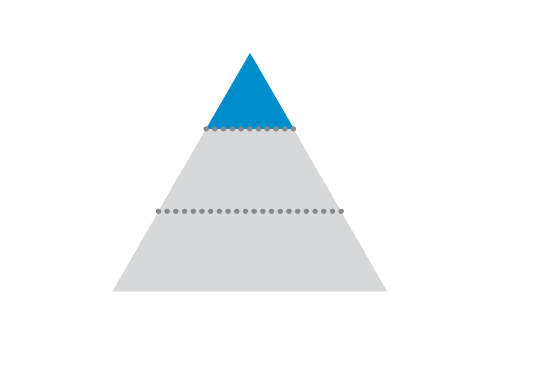

To achieve the objective of systematizing the analysis of the counterpart’s position vis-á-vis its reasoning and motives, one may use the widely accepted tool referred to as the “Iceberg” (see Figure 3).

The first step of this analysis is to ascertain or take note of the position of the counterpart (WHAT is the position of the counterpart?):

- In normal circumstances, the analysis begins with recognition of the starting position of the counterpart on the issue of the negotiation. This position is communicated from the outset of the negotiation process to humanitarian negotiators directly or indirectly, explicitly or implicitly, depending on the context, situation, and culture. At first, the position may not be very clear due to poor communication. Also, the agent transmitting the position may not carry much authority, due to, for example, having only a weak or dubious connection with the decision makers. Finally, the timing, location, or format of the communication may appear to be confusing or odd, raising questions about the authoritativeness of the communication, i.e., to what extent this communication represents the position of the counterpart or not. The context analysis step further informs this process and helps to identify the position of the counterpart. A minimum of clarity and authority must be recognized before moving forward with the analysis (see the three-pronged test in 2 | Module B: Identifying Your Own Priorities and Objectives).

A second step is to assess the reasoning of the counterpart in support of the position identified in the first step (HOW does the counterpart reach this position?):

- The tactical reasoning of the counterpart explains the logic and interest behind its position. This reasoning is tactical because it shapes the position without being its raison d’être and explains the logic through which a strategic goal or value of the counterpart is transformed into a position. Though seldom communicated by the counterpart, a member of the negotiation support team, a local staff person, or an acquaintance may elucidate the reasoning of the counterpart as part of an informal conversation. Knowledge about the reasoning of the counterpart is generally a strength, as it may help to build a new consensus on shared rational grounds. The aim of the conversation is to find a solution to the divergent, competing logical rationales rather than try to defeat the other side’s argument. Depending on the situation, it would be most conducive for discussions on the tactical reasoning of the counterpart to take place in informal quarters.

Many humanitarian negotiations take place informally, as the organization’s goal is not so much to gain a tactical advantage over the counterpart (as in a commercial negotiation), but rather to define how the parties will work together to address a common humanitarian problem.

A third step is to deduce the inner motives and values directing and informing the reasoning of the counterpart (WHY has the counterpart taken such position?):

- The inner motives and values of the counterpart are definitely of a more sensitive nature than its tactical reasoning. They may raise considerable emotions (e.g., anger, frustration, hopes, fears), especially in tense conflict environments. Yet, they are of great importance as they frame the position of the counterpart in a mantle of strict values and norms that often impose significant limitations on its ability to negotiate and find a solution. By being aware of the counterpart’s inner motives and values, humanitarian negotiators can better understand the political underpinnings of the starting position as well as the red lines that frame the rational side of the argument. The point here is not to “reason” or rationalize inner motives and values, which remain more emotional than logical, but to observe and understand the dynamic impact these values may have on the negotiation strategies of the counterpart.

The iceberg model provides an interesting analogy for such analysis. Icebergs floating in the ocean reveal only a small part of the ice to the eyes of the observers; the rest of the ice is under water. For the observer on a boat, the size and shape of an iceberg can be deduced only from the visible portion of the ice emerging above the water. The deeper the iceberg goes, the more speculative the interpretation will be from the information gathered above water. The greater the observer ‘s understanding of the iceberg and its dynamic in the fluid environment, the more able the he/she will be to predict the movement of the iceberg.

The same goes for the analysis of the position of the counterpart in a negotiation process. The more complex the rationale and deeper the motives of the counterpart are, the more complicated the interpretation will become and the harder it will be to predict the evolution of the negotiation. This will consequently require the contribution of people and experts who know about the rationale and values of the counterpart to explain the reasoning behind the position and elucidate the motives and emotions involved. Ultimately, the conduct of a negotiation, as with navigating around icebergs, must foresee the dynamic of the counterpart and integrate some level of uncertainty in terms of its interests and motives hidden from view. Ignoring this analysis can come at great cost to the negotiation and parties to the negotiation. To illustrate such analysis, one may consider an example drawn from recent practice.

Example

Health for All’s Surgical Team Retained in a Labor Dispute

Nine staff members of Health for All (HfA), an international health NGO, have been prohibited by tribesmen from leaving their residence in District A for almost a week following a disagreement between HfA and the guards of the local HfA hospital. This dispute arises from HfA’s plans to close the hospital due to decreasing war surgery needs in the region. The guards, who belong to an important tribe in the region, claim that the hospital should remain open and their compensation be paid as there are still considerable emergency health needs in the region.

The guards, supported by tribal representatives, further argue that they put their life at risk for several years to maintain the access of patients and staff to the hospital during an especially violent conflict. Some guards even lost their life in this process and others sustained long-term disabilities. Families of the guards wounded or killed during the conflict further request long-term monetary compensation for the loss of income before HfA pulls out of District A.

For now, the hospital is barely operational, with several emergency needs left unattended. Tribal leaders are increasingly concerned about the health situation in District A and insist that the hospital remain open. Families of patients have been complaining about the lack of services in the hospital.

The tribal leaders have agreed to meet with HfA representatives to look for a practical solution. The government has refrained from intervening in what they see as a private labor dispute. The army and police have only a limited presence and control over the situation in District A and would not intervene without the support of the tribal chiefs.

Before moving forward to deal with the main points of divergence with the guards (in particular, the freedom of movement and security of HfA staff), HfA negotiators will need to conduct a proper analysis of the position, tactical reasoning, and motives of the tribal leaders and the guards in order to prepare their negotiation tactics properly. In this case, questions to be examined include:

QUESTIONS

WHAT do the tribal leaders and the guards want? What are their explicit/implicit positions?

POTENTIAL ISSUES

POSITIONS AT THE NEGOTIATION TABLE

- Explicit: Tribal leaders insist on keeping the hospital fully operational.

- Explicit: The guards want to maintain their employment.

- Explicit: Families of wounded and deceased guards want to be properly compensated.

- Implicit: Retained staff will be released only when guarantees on the above are provided.

- Implicit: In the meantime, emergency needs should be addressed by HfA.

QUESTIONS

HOW did the tribal leaders get to those positions?

HOW are the tribal leaders planning to proceed?

POTENTIAL ISSUES

TACTICAL REASONING

- The retention of HfA staff has been triggered by the unexpected announcement of the closing of the hospital by HfA.

- Guards and tribal leaders were not consulted in this process. This lack of consultation questions the authority of the tribal leaders and the professional role of the guards.

- Both want their voice to be heard loud and clear by those who make such decisions. Detaining staff is the best way to get heard.

QUESTIONS

WHY do the tribal leaders take such positions? What are their inner motives and values?

POTENTIAL ISSUES

INNER VALUES AND MOTIVES

There are several values and motives at play in this context:

- In view of the rampant unemployment in District A, the only way the guards are to maintain their economic and social status is to ensure that they keep their jobs at the HfA hospital.

- The tribal leaders further see this dispute as an opportunity to gain/improve their reputation and that of their tribe within the community.

- There is a sense of inequity in the community regarding the position of HfA leaving disabled guards and destitute families of deceased guards to cope by themselves.

- Contrary to HfA statements, the health situation in District A is raising serious fears and the local HfA hospital is the only health provider still operating in District A.

This analysis will help to identify an Island of Agreement (see 1 | Tool 2: Drawing the Island of Agreements) as one develops the tactical plan of the negotiation. It will also inform the design of options and sequencing of issues to be addressed in this specific situation.

Application of the Tool

This segment presents a set of practical steps to analyze the position of the counterpart. There are three steps in building an iceberg model to analyze the position of the counterpart.

Step 1: Gather information about the position of the counterpart and evaluate its clarity and authority

The first step entails gathering authoritative information about the position of the counterpart.

In frontline negotiations, the designation of the relevant counterparts and the authority of the communication can be subject to interpretation. The lack of clarity of the starting position is often a given due to the unstable and evolving environment of the negotiation and of the conflict. However, it can also be a tactic of the counterparts to maintain a certain level of ambiguity as a matter of security about the identity of the representatives. The most authoritative information would be a direct written communication from the designated counterpart to the humanitarian negotiator for the purpose of engaging into a negotiation.

Collecting information about the clarity and authority of the position of the counterpart requires therefore a three-pronged test:

- What is the level of authority granted by the counterpart, community, or group to the particular interlocutor? What is the level of explicit representation?The more authoritative the counterpart or his/her representative is (e.g., minister, military commander, leader of an armed group, etc.), the more likely that the communication represents the position of the other side. The more ambivalent the representation is (e.g., informal communication, undocumented position, not acknowledged by the counterpart), the less authoritative the communication becomes. Self-granted attribution of an unknown agent within the community is most likely a sign of limited authority. Even though the more authoritative the information is, the more reliable it may become, less authoritative information should not be dismissed, as it may be a way for the counterpart to pass a message/position without formalizing it too much.

- What is the level of clarity of the position of the interlocutor?A clear position for a layperson (e.g., a distinct proposal, yes/no answer, or a clear counterproposal) is most likely to be authoritative as it does not require much explanation and is free from ambiguities. Convoluted positions, marred with ambiguities, are most likely to come from less authoritative sources, or have been tainted on the way to the negotiation by conflicting interests, which makes them less conclusive.

- What is the predictability about the timing, location, and format of the communication?A communication gains in authority by being transmitted in a predictable manner in terms of channel, timing, location, and format. The negotiation position of a Minister of Foreign Affairs generally comes in a written format such as a Note Verbale, not via social media. The communication of the position of a military commander is rarely late or sent to the wrong addressee. A communication by the spiritual leader in a negotiation process is unlikely to be delivered by email. It will be expected that the humanitarian negotiator will use the same form and timing in his/her return communication.

This three-pronged test is valid for both verbal and non-verbal communication, and may help the negotiation team in their internal discussion to determine the relevance and authority of a position received from the counterparts. The interpretation of any communication may have severe consequences if it is left ambiguous.

Example

Clarity and Authority of a Position in a Cross-Line Negotiation

A convoy of Food Without Borders (FWB), an international NGO, is waiting at a checkpoint to undertake a delicate cross-line operation to a besieged area. The operational plans have been submitted to the relevant military command, and the leader of the convoy is waiting for an answer at the last checkpoint before proceeding toward the no man’s land. It is understood that the security of the convoy in the no man’s land depends on the clarity of the position of the military on both sides.

Regarding the position of the military at the checkpoint:

- A first communication comes unexpectedly from a young uniformed corporal who arrives with a coffee jug, telling the convoy leader in a friendly and convivial tone: “That’s all fine. We got the authorization for the convoy. You can go ahead. Good luck!”

- A second communication is made by the officer manning the checkpoint who, looking from the window of the guard post, simply nods and, without a word, waves to the drivers to go on.

- A third communication is made by a military intelligence officer who shares his concerns with the local drivers at the checkpoint that an attack may take place in the no man’s land and that staff may be killed.

- A fourth communication detailing plans for the safe passage of the convoy comes through the radio, within earshot of the leader of the convoy, who is having tea with the officer in charge.

FWB needs to rely on the quality of the communication; it is imperative to have a clear and authoritative transmission from the counterpart to ensure the safety and security of the convoy crossing the no man’s land.

The clarity and relevance of such communication very much depend on the culture, context, and circumstances of the negotiation. Cross-line negotiation requires a high degree of clarity and authority. It also requires a solid understanding of the interests and motives of the counterpart, as the humanitarian representatives are putting their lives into the counterpart’s hands. However, in spite of a seemingly positive communication response and because of differences in logic, interests, and values, a counterpart may, in fact, act with nefarious motives. For example, the counterpart could actually be planning an attack against the convoy, in which case the attack is most likely to take place in the no man’s land where it will be difficult to attribute the attack to the counterpart forces. Therefore, the counterpart will try to convince the leader of the humanitarian convoy, through unclear or deceptive communications, to proceed in order to undertake the attack against the convoy. Several humanitarian professionals have lost their lives in such circumstances because they were not able to distinguish the true interests and motives of the counterparts in the positive response to their request to proceed into the no man’s land. The planning of an attack and the planning of a negotiation follow their own logic and value systems. There are also different protagonists involved—e.g., rogue elements wrestling for power on the frontlines vs. organized military following instructions. As the frontline negotiators seek to better understand the position of the counterpart at the entrance of the no man’s land, they will need to be careful to pick up the implicit signals (“the writing on the wall”) of one logic over the other.

The same degree of clarity and authority may apply to other negotiations on the frontlines. The greater the clarity and authority of the position, the easier the interpretation of the position will be and the more chance the negotiation will result in a positive outcome. It is therefore imperative that humanitarian negotiators be knowledgeable about the culture and context of the negotiation and be available to receive and read communications. They should seek clarification whenever needed.

Step 2: Identify the rationale supporting the position of the counterpart

The second step is to seek an explanation of the tactical reasoning of the counterpart to understand where it wants to go with its position. Rational thinking refers to a form of logic, deductive or inductive, that a third party could understand. The point is not to agree about the premise, logic, or outcome, but to be able to identify the reasoning behind the position of the counterpart. For example:

Example

Government A Intends to Maintain Its Policy of Targeting Medical Premises in Enemy Territory as They Provide Medical Support to Enemy Combatants

Health for All (HfA) considers opening a surgical clinic for war wounded close to the frontline.

The Military Commander of Government A opposes such a clinic. He explains to HfA representatives that he considers that wounded enemy combatants are targetable similar to any other military assets since they are most likely to return to combat once they have been treated by HfA staff. The military has therefore opted to target, without advance notice, medical premises where these combatants are located, even at the cost of violating clearly recognized international norms.

While the outcome of the reasoning amounts to a war crime under International Humanitarian Law (IHL), the reasoning in itself may well be logical in the context for those involved. Wounded enemy combatants represent a fortiori a military threat similar to any other military asset (such as a tank under repair would represent a targetable military asset). Under this logic, wounded enemy combatants and the premises where these individuals are treated may be attacked to gain a military advantage.

The rule of IHL drawn in 1864 protecting wounded combatants from attacks is predicated on a different military logic than the one prevailing in contemporary military circles, especially in contexts where wounded combatants can easily be treated and remobilized. Such logic needs to be considered in a negotiation about the protection of wounded combatants and medical premises, even if the humanitarian negotiators differ from that logic in view of the applicable international norms. The point here is not to agree with the logic but to understand the argument from the rational perspective of the counterpart. Such logic is likely to trigger a counterargument as part of the negotiation tactic to sway the consensus toward an alternative logic that would value the life and dignity of wounded enemy combatants in the eyes of the government and support the protection of medical premises.

Step 3: Elucidate the values and motives underpinning the position of the counterpart

The third step focuses on the values, identity, and cultural norms at play in the position of the counterpart and on which the counterpart often has little control. These values are inherent to the context and represent an ideological framework in which the counterpart operates. These values and norms need to be identified as it is unlikely that an agreement may be found without paying respect explicitly or implicitly to some of these norms. For example:

Example

Government A Implementing Religious Norms Contradicting IHL

The International Monitoring Network (IMN), an international NGO monitoring conditions of detention, is raising concerns about the application of religious norms to foreign Prisoners of War (POWs), including corporal punishments for criminal acts.

Government A maintains that POWs committing a criminal act while in detention on the territory of Country A are subject to the religious rulings of the country. Despite the fact that corporal punishments are strictly prohibited under international law, the government intends to implement the punishments in line with the religious tradition of the state.

The position of Government A to implement religious norms in lieu of international treaty-based norms is not a derivative of any legal reasoning but is a result of the prevalence of an established set of religious norms and values that are beyond the control of the counterparts to the negotiation process. These religious norms cannot be negotiated as if they were technical modalities. Rather, for both sides to this negotiation, the issue at stake is whether and the extent to which religious norms should prevail or not over other secular or international norms and be applied to the enemy POWs. Alternatively, one should determine if POW detainees should be immune from corporal punishments on humanitarian grounds in view of the exceptional circumstances of their detention and the risk of reprisals against POWs under the power of other parties to the conflict.

It is important to understand the roots of the position in terms of values and norms as the humanitarian negotiator considers the tactic of the negotiation for the protection of detainees. In particular, one may consider building a dialogue on a values-based argument enhancing the protection of POWs within the religious order of the detaining state. A negotiation at the values level is most sensitive and involves a high level of risk, as it tends to generate emotional feedback from both sides of the negotiation table. Negotiation teams are advised to undertake a careful examination of the position, reasoning, and motives of the counterparts as part of the planning process of a negotiation. While this analysis may confront some of the accepted reasoning and values sets of the humanitarian organization, it will be a significant help in the design of the tactics and discussion with the counterpart. This analysis is best conducted in a critical format, i.e., with team members challenging each other to test their understanding of the position of the counterpart.

Concluding Remarks and Key Lessons of This Tool

This segment provides a practical tool to analyze the position, reasoning, and motivation of the counterpart as key questions to deliberate with the negotiation team. This reflection should allow comparing notes in the respective understandings of the interests and motives of the counterpart. It should also facilitate the design of arguments on the organization’s own tactical reasoning and values underlining its position (see 2 | Module B: Identifying Your Own Priorities and Objectives).

To have a comprehensive iceberg as close as possible to the reality of the counterpart, the negotiator and his/her team need to invest the necessary time and effort to take notes, assess the reasoning, and deduce the motives and values of the counterpart. This practice emphasizes the importance of active listening and building a strong network within the context in order to collect the relevant information about the counterpart.

An additional aspect of the process is to recognize the deductive nature of the interpretation, i.e., how speculative it will remain in some circumstances depending on the level of access to information and ability to understand the context. The more entrenched the reasoning or the deeper the motives of the counterpart, the more speculative the negotiation team’s analysis will become. It is important therefore to diversify the sources of information and remain conservative in their interpretation. This process is singularly different from the next module about one’s own iceberg which is inductive in nature, i.e., building from known motives and the organization’s own operational planning and reasoning.

While the process may appear formulaic at times, it provides a common language and tool to discuss the analysis of the situation within the negotiation support team and encourages a critical evaluation of the counterpart’s position and its reasoning. As the team speculates on these elements, opening a critical space allows a thorough examination of the situation and informs the development of their tactical plan.

Introduction

The purpose of this segment is to explore ways to identify the priorities of a humanitarian organization in a negotiation process as well as its specific objectives within a given mandate. This module prepares for the transactional stage of the negotiation where possible options will be considered by the parties in the hope of finding an agreement.

This module builds on the analysis of position, tactical reasoning, and values of the counterpart presented earlier in Module A through the use of the “iceberg” template. It informs the tactical planning of one’s own organization for the negotiation table by setting the Common Shared Space (CSS) of the negotiation (see Module C). The main point of Module B is to support the development of a tactical plan that will allow for bridging the gap between the positions of the counterpart and those of one’s own organization.

Tool 10: Identification of Your Own Priorities and Objectives

At the point of departure, priorities and objectives of a negotiation process are drawn from the strategic objectives and mission of the organization and the limitations entailed in its institutional policies guiding the options available to the negotiator. The mandate frames the negotiation process in terms of both of these aspects.

The objectives of the negotiation are generally the product of a discussion with the hierarchy of the organization. The mandate embodies the authority given by the hierarchy of the organization (the mandator) to the humanitarian negotiator (the mandatee) to negotiate in the name and for the benefit of the organization. The mandate specifies the objectives and limits of the tasks required from the mandatee, including the expected methods and reporting lines to be used. However, contrary to traditional instructions to staff or agents, the mandate provides a high degree of autonomy to the mandatee on how to conduct the negotiation within the limits set by the mandate. The concept of the mandate plays a critical role in this context. Compared to a representation role, the mandate of a negotiator provides significant space to explore options with the counterpart and delegates an authority to determine the best possible outcome of the negotiation within the limits set by the mandator.

There are many types of mandates in the humanitarian sector: states have mandated humanitarian organizations to offer their services in times of conflict; local authorities may mandate an NGO to manage a camp; patients may mandate a physician to undertake a life-saving surgery. There are also a number of internal mandates within an organization (in addition to instructions given to its employees and agents). Specific examples of the range of mandates: a nurse can be mandated to run a clinic; a pilot can be mandated to fly an aircraft; an architect can be mandated to build a hospital. These mandates accord a certain level of autonomy to the agents in their respective profession, while other actors (such as accountants, logisticians, radio operators, drivers, etc.) are instructed to function within tighter technical constraints.

Frontline humanitarian negotiation is a specific mandate given to designated staff that comes with considerable autonomy—but also with red lines. Negotiation mandates for certain representatives (e.g., head of office, team leader, country director, etc.) are often combined with parallel and more constrained responsibilities. The systematization of the methods of frontline humanitarian negotiators and the creation of a community of practitioners aim at increasing the level of autonomy of the mandatee within recognized professional standards. Section 3 | Tool 15: Design of the Mandate will elaborate the details of negotiation mandate. The aim of this module is to facilitate the identification of the priorities and specific goals of an organization in a negotiation process from the interpretation of the mandate of the negotiator.

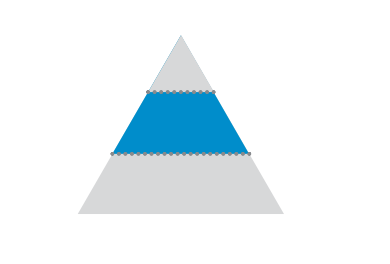

To identify negotiation priorities and objectives, it may be useful to mirror the reasoning and motives analysis of the counterpart presented in the previous Module using the same iceberg, but this time focusing on one’s own organization, starting from its values and motives, to examining its tactical reasoning and professional standards, and finally ascending the iceberg to the position of the organization in the particular negotiation that will be communicated to the counterpart.

Based on the mandate received from the organization and looking into the context analysis, the main questions are therefore:

The logic of building one’s own iceberg is the reverse of interpreting the position of the counterpart. One can only interpret the tactical reasoning and motives of the counterpart starting from the counterpart’s position as communicated at the negotiation table. But to formulate one’s own humanitarian organization’s position, there is the advantage of having a known set of values and norms that informs the organization’s operational reasoning in the form of methods, professional standards, and programmatic objectives. These, in turn, will indicate the starting position of the humanitarian organization in the specific negotiation. This position is then communicated to the counterpart from the outset of the negotiation. Hence, the values and identity of the humanitarian organization serve as a bedrock for defining its reasoning and mode of operation, which will then establish a starting position on the technical modalities of the operation to be negotiated. It is important to build the organization’s iceberg in such a way as to be able to explain its position in a negotiation through the various angles at any point of the negotiation. This communication will also facilitate the passages between different types of negotiation, namely:

- From political negotiation about the organization’s values and identity (WHO are you? WHY are you here?);

- To a professional negotiation about tactics and modes of operation (HOW do you operate?);

- To a technical negotiation about the position on the modalities of the operation (WHAT do you need? WHERE will you work? WHEN will you start? etc.)

Application of the Tool

This segment presents a set of practical steps to build a strong and coherent approach for one’s position at the negotiation table using the tool presented above on the recent example drawn from practice introduced in the previous modules. It builds on the same situation from the preceding Module.

Example

Health for All’s Surgical Team Retained in a Labor Dispute

Nine staff members of Health for All (HfA), an international health NGO, have been prohibited by tribesmen from leaving their residence in District A for almost a week following a disagreement between HfA and the guards of the local HfA hospital. This dispute arises from HfA’s plans to close the hospital due to decreasing war surgery needs in the region. The guards, who belong to an important tribe in the region, claim that the hospital should remain open and their compensation be paid as there are still considerable emergency health needs in the region. The guards, supported by tribal representatives, further argue that they put their life at risk for several years to maintain the access of patients and staff to the hospital during an especially violent conflict. Some guards even lost their life in this process and others sustained long-term disabilities. Families of the guards wounded or killed during the conflict further request long-term monetary compensation for the loss of income before HfA pulls out of District A.

For now, the hospital is barely operational, with several emergency needs left unattended. Tribal leaders are increasingly concerned about the health situation in District A and insist that the hospital remain open. Families of patients have been complaining about the lack of services in the hospital.

The tribal leaders have agreed to meet with HfA representatives to look for a practical solution. The government has refrained from intervening in what they see as a private labor dispute. The army and police have only a limited presence and control over the situation in District A and would not intervene without the support of the tribal chiefs.

Step 1: Build the iceberg of the organization’s own position starting from its values and motives

The purpose of this module is to open a space of exploration with the counterpart in terms of possible arrangements between the two parties so as to reach an agreement. It prepares for the transactional stage of the negotiation where possible options will be considered by the parties in the hope of finding an agreement.

Building on the questions presented previously in the interests and motives analysis module, one can elaborate the position of HfA starting from the values and motives of the organization and ascending up HfA’s iceberg toward the entry position at the negotiation table. The point of departure in this case is from the values and motives, rather than the position (as in the case of the counterpart analysis), since there is no need to speculate or interpret them—they are part of the genesis of the mission and presence of HfA in this context.

QUESTIONS

WHO is HfA? What values define HfA as a humanitarian organization?

WHY does HfA want to operate in this context?

POTENTIAL ISSUES

INNER VALUES AND MOTIVES

The mission and identity of HfA are predicated on several elements that are of relevance in this particular context:

- HfA is a humanitarian organization. It operates under a set of principles detailed in its mission statement (neutrality, impartiality, proximity, etc.).

- It aims to ensure equitable access to health care for ALL, with special attention to the surgical needs of the most vulnerable in District A. It aims to complement existing services, public and private.

- It is an ethical organization committed to respecting medical ethics and the privacy of the patient. It is bound by the human rights of patients.

- It is a non-profit organization providing free services to populations in need of health care.

- It is transparent, well managed, and a diligent employer keen to maintain good relationships with the people and communities it serves.

- While it has limited resources, it strives to do its best to ensure the continuity of access to health care as long as there are needs falling within its mandate.

- In the particular context, it appears that there are segments of the population deprived of access to essential health care services. This context falls within the mandate of HfA as long as these needs are present.

QUESTIONS

HOW does HfA intend to operate?

WHAT are the specific methods?

POTENTIAL ISSUES

TACTICAL REASONING

- As a professional organization, HfA maintains professionally recognized protocols in terms of medical services, managerial methods, and financial accountability to donors.

- It maintains a dialogue with the community and local health professionals around assessing the needs of the population.

- As a private charitable organization, HfA has the authority to decide on its priorities and objectives. It needs to consult regularly with local leaders and communities on the development of its activities.

- It is also accountable to the health authorities of District A in terms of its role and objectives in the health care system of the district.

- In terms of security of staff and premises, it hires guards from the community to help secure the buildings (hospital, clinics, residence of staff) in accordance with applicable legislation and local customs. The guards are lightly armed due to the high level of armed and criminal violence in the context.

- A direct link is maintained between HfA guards and the local police force.

- In view of the tribal character of the society, the selection of the guards is made in consultation with tribal leaders who will propose and review candidates.

QUESTIONS

WHAT does HfA want out of this negotiation? Under what terms does it wish to operate? What is HfA’s position? How does it want to communicate this position?

POTENTIAL ISSUES

POSITIONS AT THE NEGOTIATION TABLE

- HfA insists on the immediate release of all HfA staff and their evacuation from District A.

- Tribal leaders must guarantee the safety and well-being of HfA staff, in the meantime.

- HfA scales down its surgical activities in the region and hands over the hospital as well as obligations toward the guards and their families to a third party.

- Meanwhile, HfA engages in consultation to rebuild trust with the community.

Concluding Remarks and Key Lessons of This Tool

In a complement to the iceberg of the counterpart, this segment provides a parallel tool to apply the values and motives of the humanitarian organization to its reasoning and methods, which in turn can define and explain the position to be asserted at the negotiation table.

This reflection will support and guide the frontline negotiator in capturing and analyzing information from the counterpart, as well as in creating a nuanced relationship with the counterpart. It will further allow for the opening of a Common Shared Space for the negotiation and shifting the mindset of the negotiating team from advocating for one’s position to finding ways to build co-ownership on the negotiation options.

Tool 11: Exploring the Common Shared Space

The purpose of this module is to open a space of exploration with the counterpart in terms of possible arrangements between the two parties so as to reach an agreement. It prepares for the transactional stage of the negotiation where possible options will be considered by the parties in the hope of finding an agreement.

This module builds on the analysis of interests and motives of counterparts and of one’s own organization presented earlier in the earlier Modules A and B through the use of the “iceberg” template. It informs the tactical planning by setting the Common Shared Space (CSS) that will in turn inform the location of the red line and bottom lines of the negotiation discussed in Module D. The main point of this module is to support the development of a tactical plan that will allow for bridging the gap between the position of the counterpart and those of our own organization.

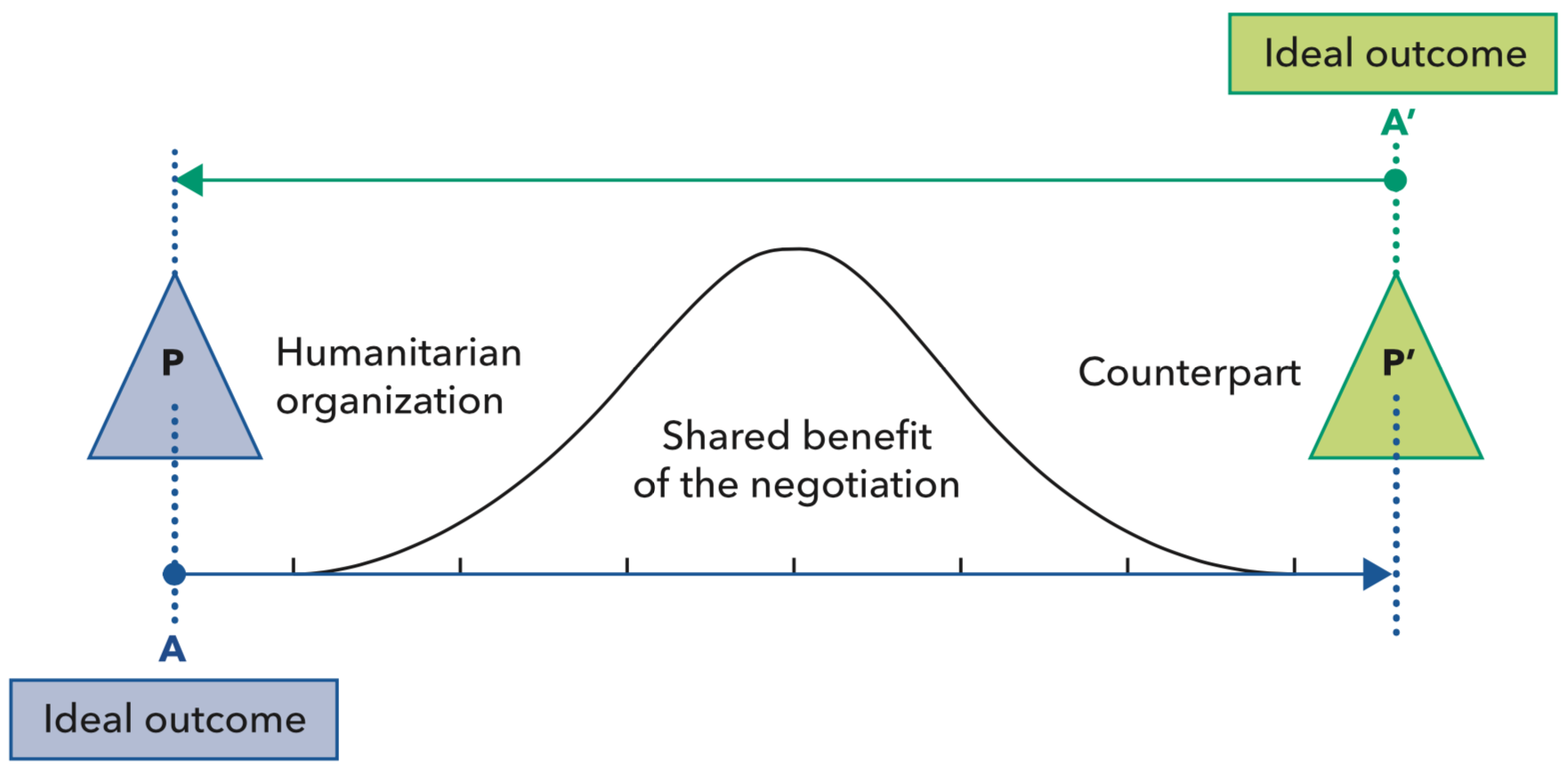

Drawing the Common Shared Space

Humanitarian negotiation essentially involves the exploration of a shared space—as distinct from the “humanitarian space”—where parties to the negotiation can safely review values, methods, and parameters of a proposed operation. The more trustful and predictable the relationship is, the more fertile the exploration of potential areas of convergence will be. This search for convergence is in contrast with the work of humanitarian advocates whose role is to protect the humanitarian space and to convince the other side to respect the entitlements of the humanitarian organization.

The co-ownership of the negotiation process is a fundamental characteristic of robust relationships. Ultimately, a final agreement is as much the product of the humanitarian organization’s efforts and those of the counterpart.

To succeed, a negotiation must be more than a competition between two narratives. Parties must be able to generate a substantive dialogue on values, methods, and the details of relief and protection operations as a means to generate an implementable and impactful agreement. It involves an ability to distance oneself from his/her position—distancing from one’s own iceberg made of principles, methods, and positions—and meet the counterpart to explore opportunities of agreements.

Such an approach involves a shift of the ethos of humanitarian professionals from the original guardian of the humanitarian space to a new philosophy and attitude pertaining to negotiators. It may at times be a challenge for humanitarian professionals to distance themselves from their own values, norms, and methods in order to engage genuinely in an exercise of exploration of potential compromises with the counterparts. This module is designed to help humanitarian negotiators process the required information and develop the right attitude.

Since this Manual focuses on the specific role of the frontline negotiator, this segment will articulate legitimacy and trust through the viewpoint of the individual negotiators rather than the ones of organizations and systems. The legitimacy of the humanitarian negotiator as well as the one of the counterpart play a critical role in the success of humanitarian negotiation. Major concessions are obtained by virtue of the personal status and skills of frontline negotiators. Conversely, misperceptions about the negotiator’s status or insufficient personal skills may be critical impediments to access in some conflict environments. This point could easily undermine the confidence of many professionals in the field, as no one can feel totally assured that they have the status and personal skills required to seek access to people in need or feel certain that what they bring to the negotiation will be sufficient to guarantee the security of an operation.

From Differences Between the Parties to Opportunities of Agreement

Rather than see the distance as an obstacle, frontline negotiators interpret this space as the area of professional engagement with the counterpart, the Common Shared Space of the negotiation where the parties will explore areas of potential shared values, shared reasoning, and shared positions which may end up in the final agreement.

Building on the analysis of both parties’ interests and motives (see 2 | Module A: Analysis of Interests and Motives and 2 | Module B: Identifying Your Own Priorities and Objectives) the negotiator is able to determine the distance between his/her organization and the counterpart. This space is composed not only of the shared possibilities, but of all the options, including those disagreeable to one or both of the sides. The goal of the dialogue between the parties is to sort out and understand their respective preferences and objections.

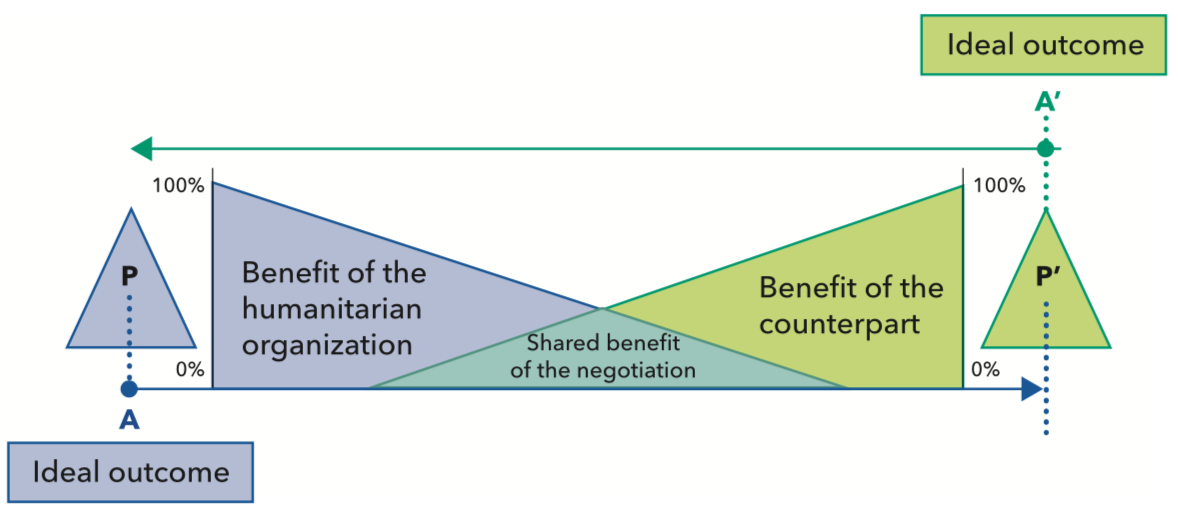

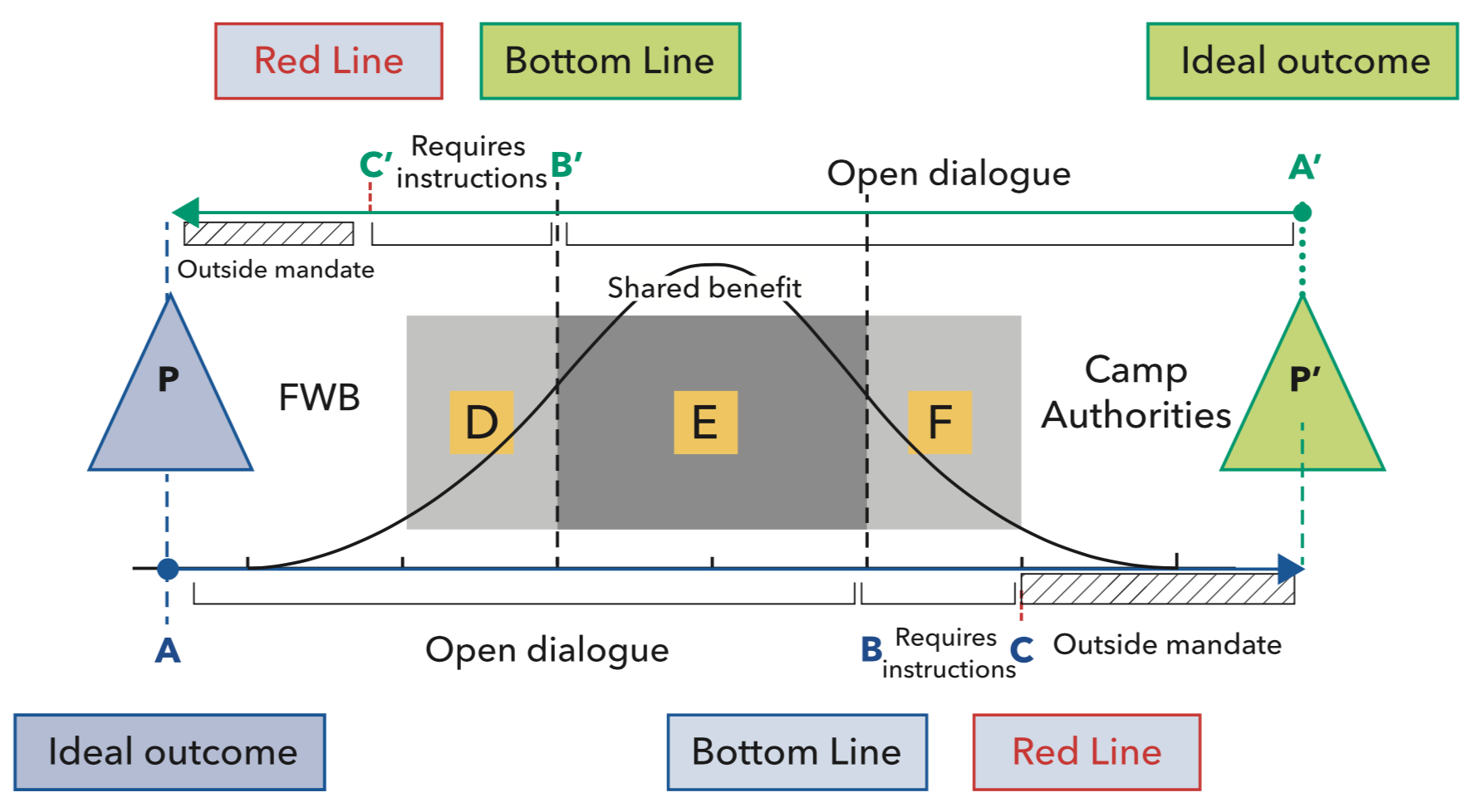

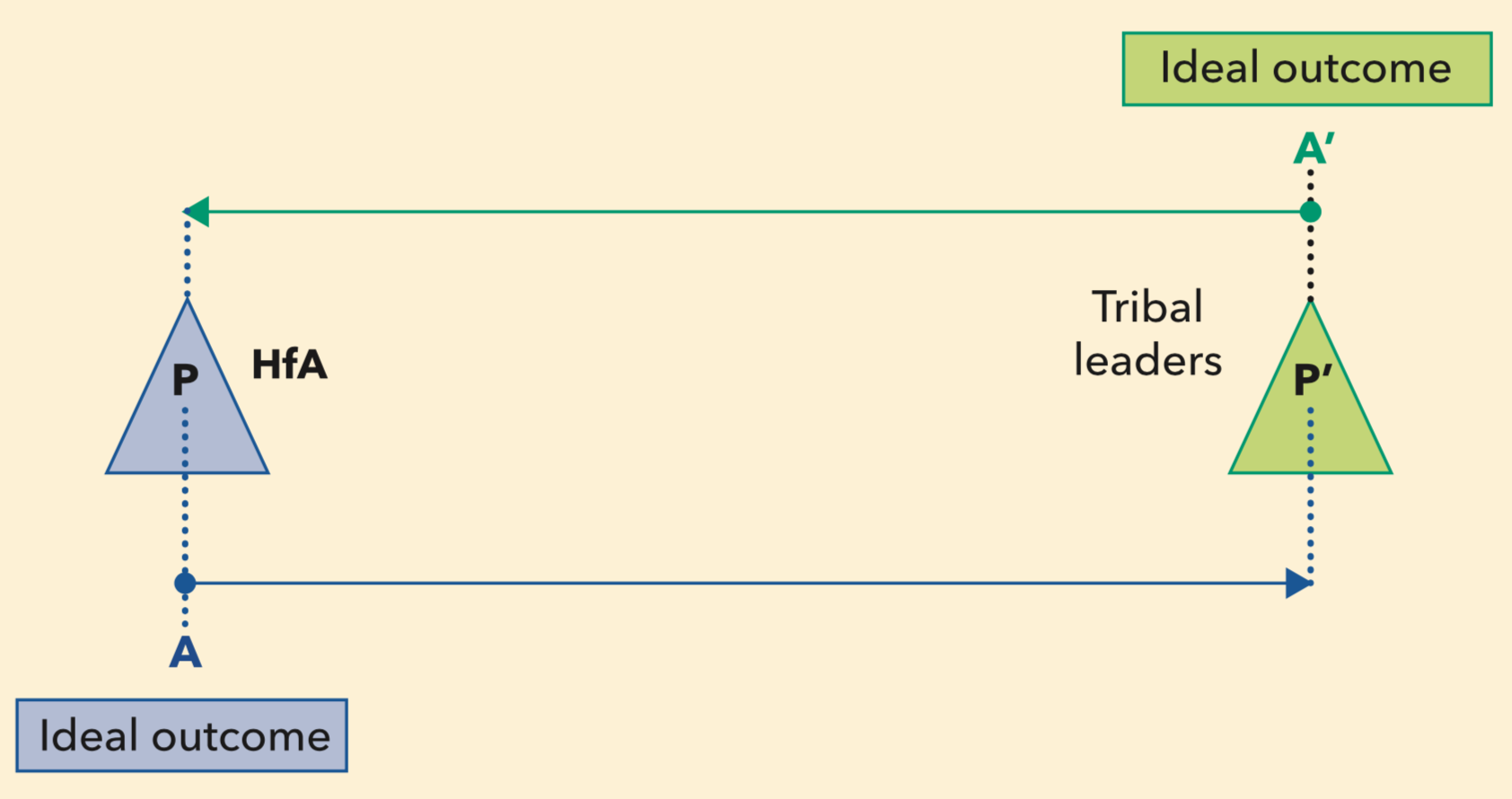

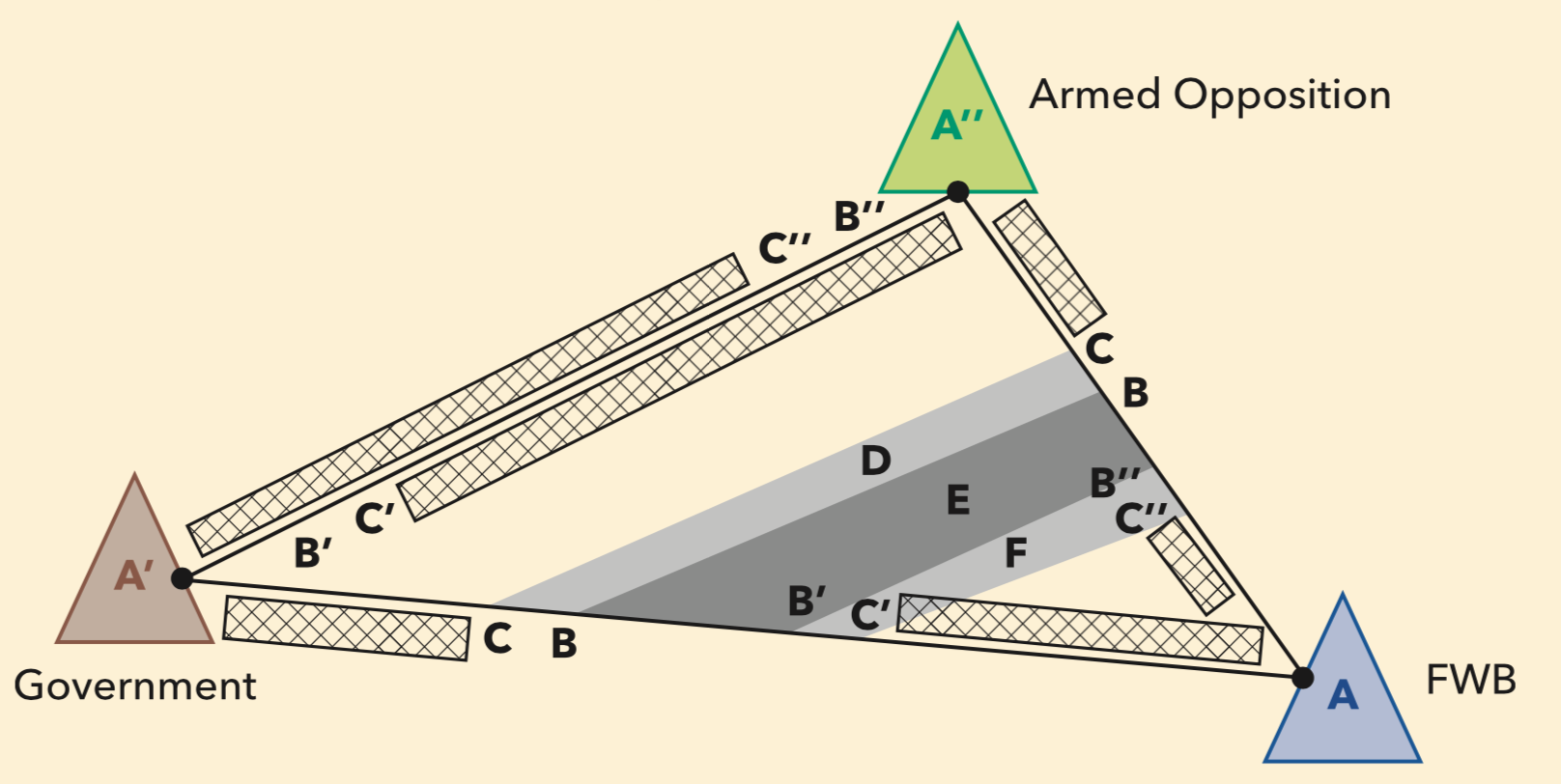

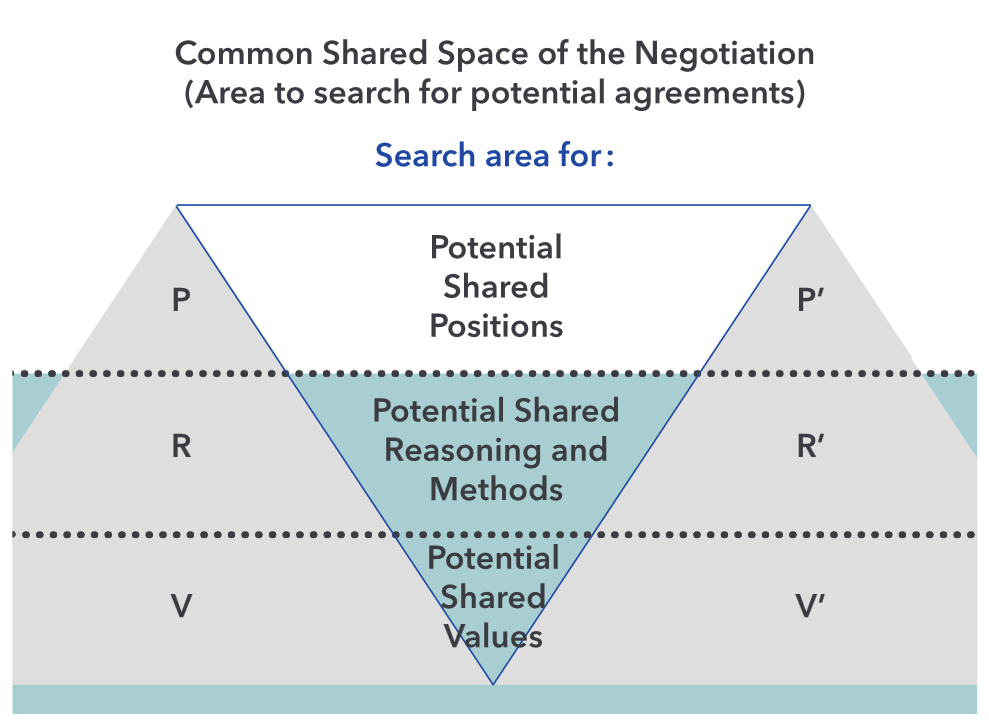

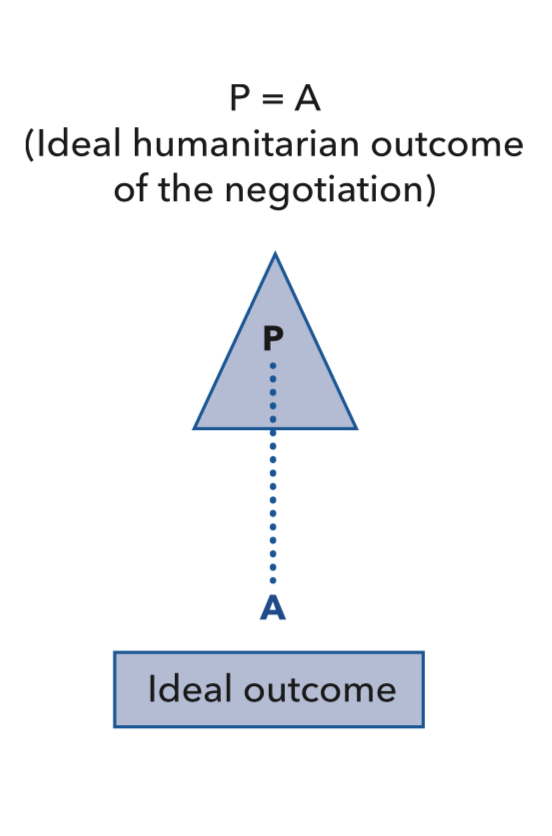

Figure 6: Defining the Common Shared Space of the Negotiation

Identifying the area of the negotiation therefore involves:

- Communication of the respective positions of the parties (P) and (P’);

- The ability to explain one’s tactical reasoning (R) and connect it to the reasoning of the counterpart (R’);

- The openness to discuss one’s underlying values and norms (V) in a language and method that may relate to the values and identity of the counterpart (V’); and,

- The recognition of the distance between the two sets of positions/methods/values in order to offer an opportunity for dialogue and improved understanding of the counterpart. In this Common Shared Space of the negotiation, which is co-owned by the negotiators, it is hoped that the parties are willing to find a compromise.

The negotiation should be presented as a process for the parties to explore ways to reconcile P, R and V with and P’, R’, and V’. For example:

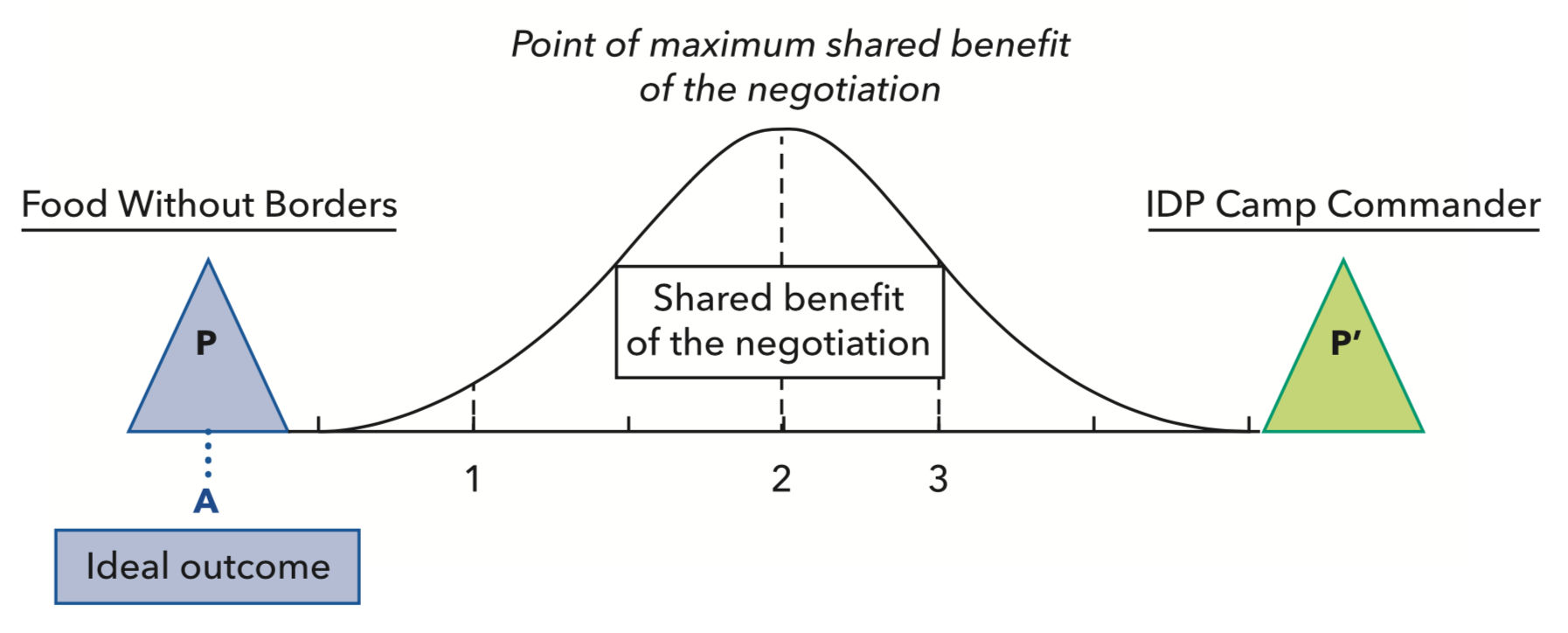

Food Without Borders (FWB), an international NGO, is negotiating access to IDP camps with the Governor of a remote district of Country A. Because the rainy season has paralyzed access by road to the district, FWB is also seeking access to the local airstrip, which is under the control of the Governor. The movement of the food within the district will further require the security guarantees of the Governor and the leaders of the local militia under his control.

The object of the negotiation relates to access to IDP camps. This negotiation involves several technical issues, such as:

- Landing rights for humanitarian flights;

- Timing and itinerary of humanitarian convoys; and,

- Location and number of beneficiaries within the population of the IDP camp.

The reliance on the agreement by the parties and its implementation involve operating procedures and methods that need to be clarified at the tactical reasoning level, respectively:

- Common understanding on flight pathways and communication procedures;

- Common protocols of checkpoints and communication procedures with the militia; and,

- Common understanding on the terms of the presence and role of FWB staff in the IDP camp.

These elements of tactical reasoning are, in turn, inspired by the values and norms of the parties, hence:

- Respect for the national sovereignty and control over airspace and air operations;

- Respect for key principles in the distribution of the food to the IDPs; and,

- Respect for the counterpart’s authority over the population and security of the camp.

In other words, while the agreement with the Governor may focus on technical issues, namely, the use of the airstrip, the movement of trucks within the district, and the operations in the IDP camps, the quality and durability of the agreement in terms of implementation require a thorough engagement at the values and reasoning levels of the conversation. The frontline negotiator is well advised to take the time necessary to explore the Common Shared Space as to ground technical arrangements in a sound and shared understanding of the respective positions, reasoning, and values between the parties.

Understandably, some negotiations may already have a strong focus on diverging values (e.g., on the visibility of an emblem) or diverging tactical reasoning and methods (e.g., on the terms of the distribution of the food) that will frame further discussion on the activities of the organization at a more technical level. This focus implies that negotiators on both sides will concentrate their energy on exploring the Common Shared Space at the technical level while paying attention to the implications at the other levels. For example:

The leader of the militia objects to the use of the logo of FWB on the convoys crossing the territory under his control. He requires that all displays of the FWB logo be withdrawn from the trucks.

The humanitarian negotiator must discern if the position of the militia results essentially from:

- A disagreement about where and when the logo is being displayed (technical level);

- A divergent understanding of how the logo is being used to identify the FWB’s convoy (on the door, on flags, on the roof top, etc.) (tactical/professional reasoning level); and/or

- A divergent understanding of the meaning and implications of the logo (values level).

Issues of logos tend to focus on the “message” the logo carries, notwithstanding the intent of the organization. In this case, the leader of the militia believes that the logo is offensive toward the local culture.

Depending on the level of engagement and trust, the humanitarian negotiator will focus the search for potential agreements on the most promising areas, i.e., where the relationship has most traction, selecting, alternatively, these search areas:

- V <-> V’: The organization already has good connections with militia members as well as with religious scholars and community leaders in the region. They may recognize the non-religious and non-political character of the logo;

- R <-> R’: The organization is recognized as a professional entity. Professionals in the region may vet for the professional use of the logo so as to identify the service of the organization and ensure the security of the personnel; and

- P <-> P’: The convoys of the organization are already operating and recognized in the region and can accommodate varying degrees of visibility of its logo in the course of its operations without hindering its security. It will require a more thorough management and notification process so as to avoid any misperceptions of the humanitarian and protected nature of the convoys.

In all cases, the first step is about understanding the perspective of the counterpart and seeing how to reconcile possible divergences at the various levels of engagement. (For a more detailed discussion on the various types and levels of engagement, see 1 | Tool 4: Determining the Typology of a Humanitarian Negotiation.)

Starting with Values: Reformulating divergent beliefs into shared values

Going back to the exploration of the Common Shared Space, this segment will focus on a systematic search for shared values.

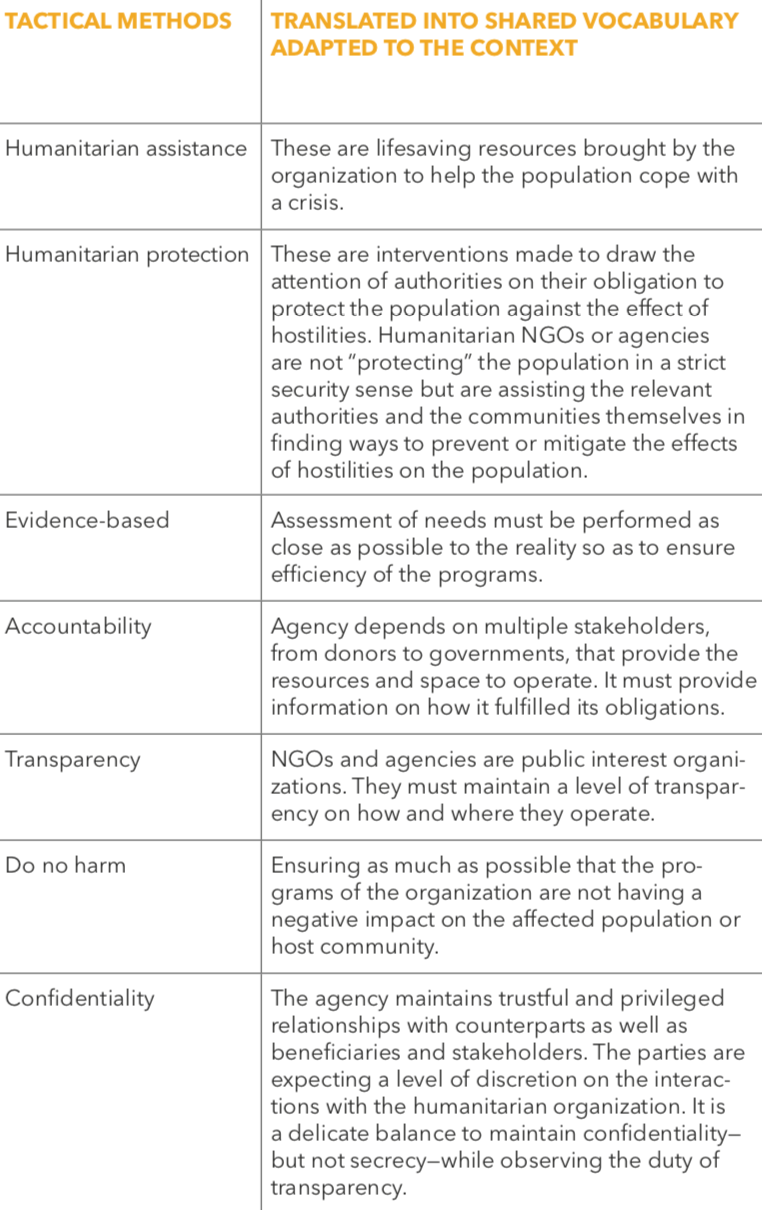

Searching for shared values is about finding overlap between the structure of beliefs of both sides and reformulating these values into a common shared vocabulary. (For a more detailed discussion on engaging on values and norms, see 1 | Tool 5: Drawing the Pathway of a Normative Negotiation.) A key aspect of the process for humanitarian negotiators is to understand that they need to move beyond the rhetoric of “humanitarian principles” to be able to explain the meaning and relevance of each of the principles in the particular context. Humanity, Impartiality, neutrality, and independence are values and norms that belong to the humanitarian community, not the parties to an armed conflict. Yet, some aspects of these norms can certainly be shared if presented in a meaningful and relevant way in the eyes of the counterparts. Hence, humanitarian principles need to be unpacked and “translated” into a palatable vocabulary for the counterpart so he/she can recognize common beliefs. For example:

The same applies to tactical reasoning and professional methods which are measurable by their capacity to mobilize a consensus among peers on HOW the organization should operate in the affected territory. There are a number of procedures and mechanisms that make a lot of sense for humanitarians but have little resonance with counterparts. These methods need to be unpacked as well in order to become tangible points of the conversation so both sides may agree on how to handle the humanitarian needs of the population. For example:

Finally, the position of the organization should be communicated clearly so that the counterpart both understands where the organization stands and perceives its willingness to engage. (For more details, see Section 1 | Fostering Legitimacy and Building Trust). Introduction of technical terms can also launch a new tangent of discussion, especially in areas of chronic emergency requiring multi-year responses, where the humanitarian lexicon can be misinterpreted or misused by counterparts. Hence, one should avoid language in a position that pre-empts a conversation or closes the door to the exploration of potential agreements, such as:

- “Under international law, we have the right to …”

- “Our organization will never accept …”

- “This position is non-negotiable.”

- “We are not willing to discuss this point.”

- “This situation is unacceptable.” Etc.

The doctrine of the organization may indeed prohibit specific arrangements proposed by the counterpart. The leadership of the organization may even call for a denunciation of the action of the counterpart. Yet, the mandate given to the humanitarian negotiator is to engage in a conversation with the counterpart, explore possibilities, and build trust, not to prohibit or denounce their action. The mandator (e.g., country director of the organization) should be the one communicating the strong prohibiting messages. Organizations must maintain the credibility of the role of frontline negotiators by sparing them from acts of denounciation or intimidation towards the counterpart. Frontline negotiators must not hesitate to request or insist on this kind of support from the negotiation team in order to preserve their place and relationship with the counterpart.

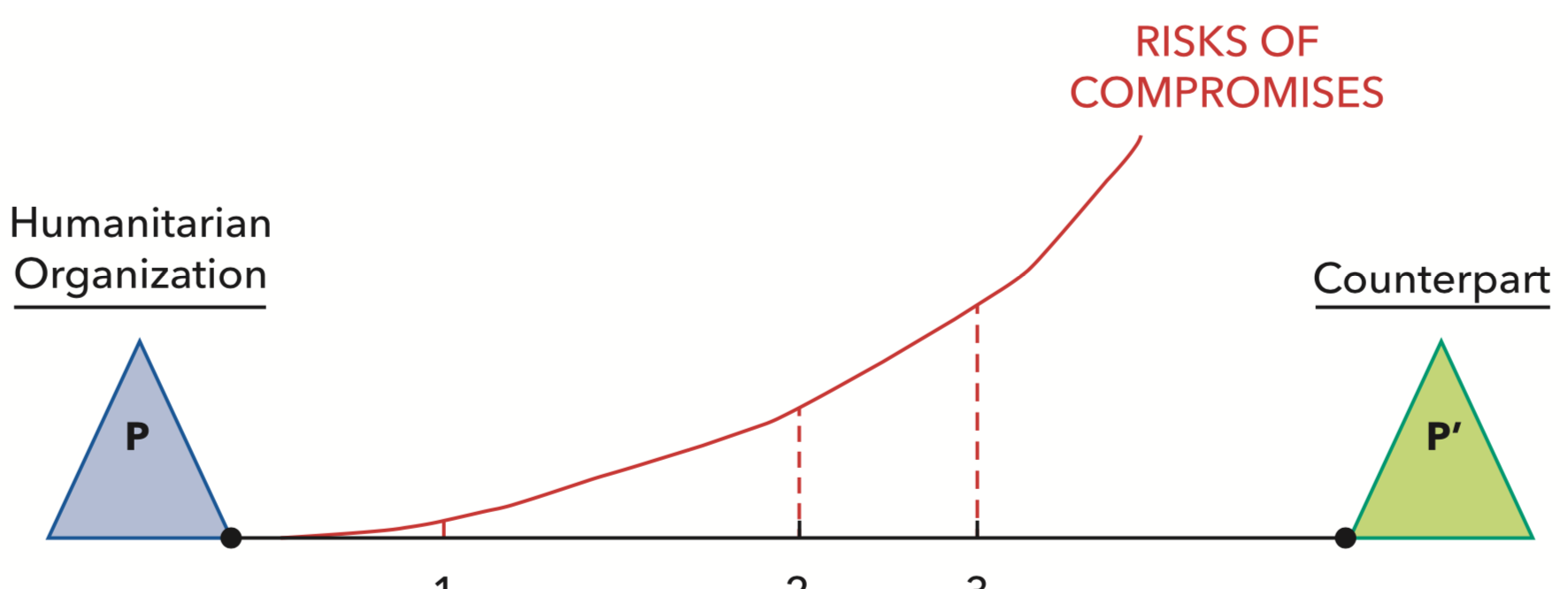

It is well understood that there will be a time to set clear “red lines” and manage expectations, which is also part of the job of frontline negotiators. Yet, the conversation on red lines can take place only if and when the level of dialogue and the engagement between the negotiators are sufficiently developed. To start a conversation by stating the red lines is an act of power subjugating the Common Shared Space to the terms of one side. It is recommended therefore that the opening position focuses on stating what the organization wants and is not construed as a negative assertion (i.e., stating what the organization rejects) as a way to open a dialogue on the views of the other side without restrictions.

Application of the Tool

As mentioned above, the Common Shared Space is a derivative of the analysis of the two icebergs and their juxtaposition. It allows for the identification of options to be explored in a first step informed by the previous identification of agreed facts and convergent norms (see 2 | Tool 2: Drawing the Island of Agreements), to be followed by the design of the scenarios and red lines which are presented in the next module (see 2 | Module D: Designing Scenarios and Bottom Lines).

The CSS is very much inspired by the Island of Agreement exercise as well as the Typology of a Humanitarian Negotiation presented in 1 | The Frontline Negotiator. The connection between these tools should be well understood.

On the Interface Between the Island of Agreement and the Common Shared Space

The Island of Agreement presented in 1 | The Frontline Negotiator and the CSS introduced in this module are important tools in the planning process of a humanitarian negotiation. While they are inspired by the same idea of sorting elements to find a conducive pathway for the negotiation, they serve different purposes:

- The Island of Agreement is a tool assisting the humanitarian negotiator in establishing a positive dialogue with the counterpart on all aspects of the situation as a basis for a trusted relationship despite potential divergences on norms and/or disagreements on facts; while …

- The Common Shared Space serves as a tool of the negotiation team identifying the convergence between the parties on specific aspects of the negotiation in terms of values, tactical reasoning, and technical positions to serve as a basis for the search for an agreement on a specific transaction between the parties.

Hence, one should be careful to keep these two tools distinct as they serve different purposes. There are objects of agreement and convergence in the Island of Agreement that are not relevant to the transaction. There are objects in the CSS model that need to be confirmed through the exploration of the space of potential transaction.

On the Interface Between the Typology of Negotiation and the Common Shared Space

Likewise, there are clear points of contact between the typology assessment presented in the tactical planning section and the CSS presented in this module. While the two are interconnected, there are, however, some differences in the use of the respective tools:

- The typology model is designed to help the humanitarian negotiator in selecting the tactical angles of his/her negotiation (political vs. professional vs. technical), as well as identifying the tactics and required human resources to bring to the table; while …

- The CSS model is designed to help the negotiation team sort out the substantive values, tactical reasoning, and position of the parties and review potential options for agreement.

These tools work together in a sequenced manner as the humanitarian negotiator and the accompanying negotiation team work through the planning process. This particular module is designed to support the deliberation between the negotiator and his/her negotiation team where options for the transactional stage are being discussed, drawing from the same taxonomy of the Naivasha Grid, taking the situation described in the previous module and building on the analysis of both icebergs:

Example

Health for All’s Surgical Team Retained in a Labor Dispute

Nine staff members of Health for All (HfA), an international health NGO, have been prohibited by tribesmen from leaving their residence in District A for almost a week following a disagreement between HfA and the guards of the local HfA hospital. This dispute arises from HfA’s plans to close the hospital due to decreasing war surgery needs in the region. The guards, who belong to an important tribe in the region, claim that the hospital should remain open and their compensation be paid as there are still considerable emergency health needs in the region. The guards, supported by tribal representatives, further argue that they put their life at risk for several years to maintain the access of patients and staff to the hospital during an especially violent conflict. Some guards even lost their life in this process and others sustained long-term disabilities. Families of the guards wounded or killed during the conflict further request long-term monetary compensation for the loss of income before HfA pulls out of District A.

For now, the hospital is barely operational, with several emergency needs left unattended. Tribal leaders are increasingly concerned about the health situation in District A and insist that the hospital remain open. Families of patients have been complaining about the lack of services in the hospital.

The tribal leaders have agreed to meet with HfA representatives to look for a practical solution. The government has refrained from intervening in what they see as a private labor dispute. The army and police have only a limited presence and control over the situation in District A and would not intervene without the support of the tribal chiefs.

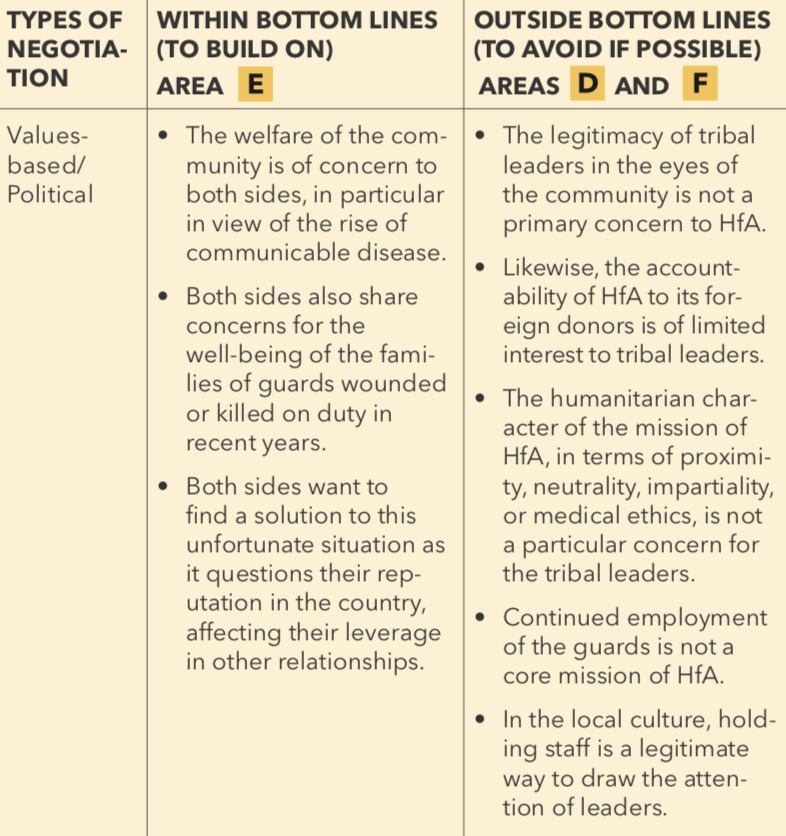

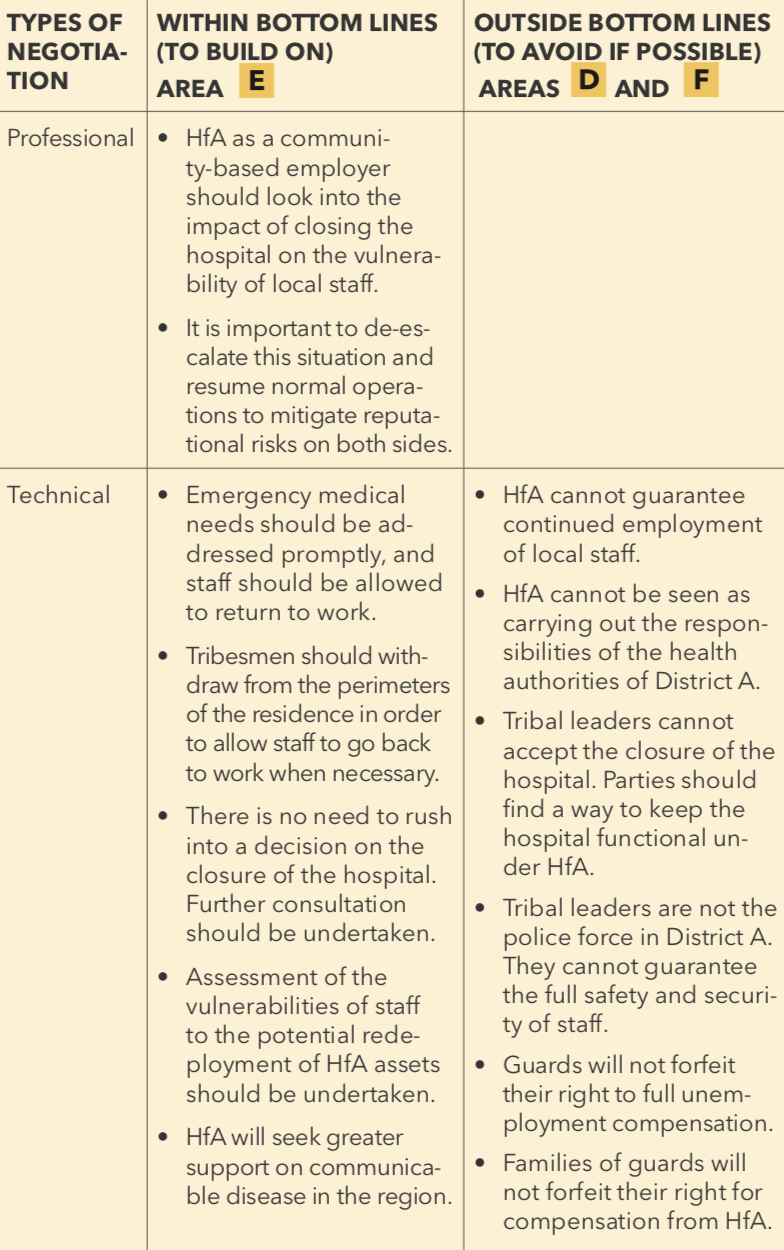

In this case, the range of options includes areas of potential shared objectives at each level of the negotiation. Discussions should allow the co-ownership of the Common Shared Space and see how it can address expectations on other elements in a second step.

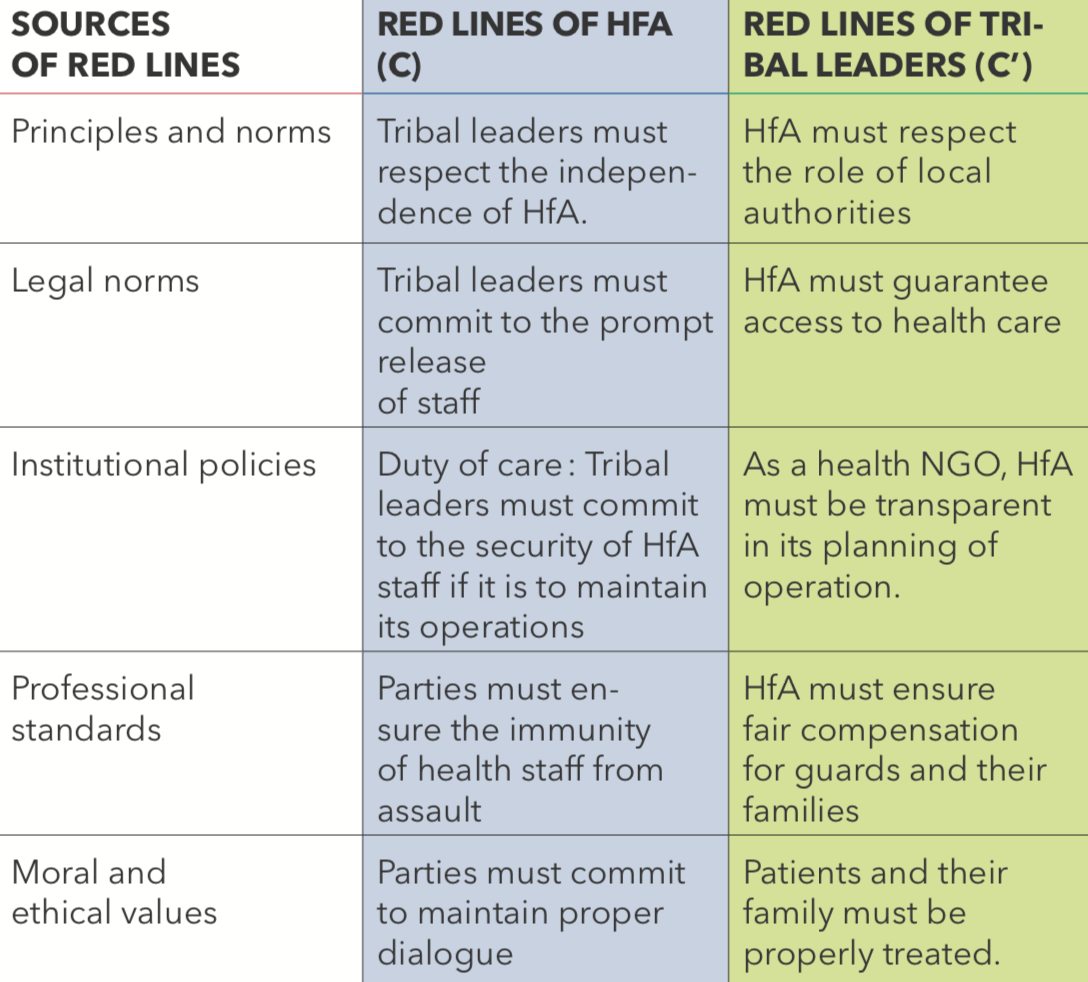

Step 1: Assess the potential shared values by building on the iceberg assessment mentioned in the previous modules

CONVERGENT ELEMENTS TO SERVE IN EXPLORING THE CSS

- The welfare of the community is of concern to both sides, in particular in view of the rise of communicable disease.

- Both sides also share concerns for the well-being of the families of wounded guards and those killed on duty in recent years.

- Both sides want to find a solution to this unfortunate situation as it questions their reputation in the country, affecting their leverage in other relationships.

- Both sides appreciate the importance of evidence-based decision-making, ensuring objective policies in terms of community health.

DIVERGENT ELEMENTS TO LEAVE ASIDE

- The legitimacy of tribal leaders in the eyes of the community is not a primary concern to HfA.

- The humanitarian character of the mission of HfA, in terms of proximity, neutrality, impartiality, or medical ethics, is not a particular concern for the tribal leaders.

- Continued employment of the guards is not a core mission of HfA.

Step 2: Assess the potential shared reasoning by building on the converging values mentioned above

CONVERGENT ELEMENTS TO SERVE IN EXPLORING THE CSS

- The safety and security of staff are common goals of both sides.

- It is important to de-escalate the situation and resume normal operations to mitigate reputational risks on both sides.

- Greater consultation with the community and the tribal leaders is part of the solution.

- It is important to restore the activities of the hospital and ensure the integrity of its staff and premises.

- There needs to be an assessment of the rise of communicable disease in District A.

- There needs to be an assessment of the vulnerability of families of injured guards and guards killed on duty over recent years.

- HfA as a community-based employer should consider the vulnerability of local staff as an impact of closing the hospital.

DIVERGENT AREAS TO LEAVE ASIDE

- Health care is a public service. By working in this domain, HfA may have forfeited part of its autonomy of decision-making to local leaders and community.

- Holding staff is a way of drawing attention from foreign leaders.

- HfA is a charitable organization accountable to its foreign board and donors.

- The presence and roles of local law enforcement and authorities vs. tribal leaders in this matter are problematic.

- Tribal traditions should be the governing standard of labor relations between HfA and its local staff and a measure of the liabilities of HfA toward employment of the guards and compensation of the families of injured or killed guards.

Step 3: Consider the scope of potential shared positions of the negotiation by building on the two previous steps

POTENTIAL AREAS OF AGREEMENT

- Medical needs should be addressed promptly, and staff should be allowed to return to work.

- Tribesmen should withdraw from the perimeters of the residence so as to allow staff to go back to work when necessary.

- There is no need to rush into a decision on the closure of the hospital. Further consultation should be undertaken.

- Assessment of the vulnerabilities of staff to the potential redeployment of HfA assets should be undertaken.

- HfA will seek greater support on communicable disease in the region.

POTENTIAL AREAS OF DISAGREEMENT

- HfA cannot guarantee continued employment of local staff.

- HfA cannot be seen as carrying out the responsibilities of the health authorities of District A.

- Tribal leaders cannot accept the closure of the hospital.

- Tribal leaders are not the police force in District A. They cannot guarantee the full safety and security of staff.

- Guards will not forfeit their right to full unemployment compensation.

- Families of guards will not forfeit their right for compensation.

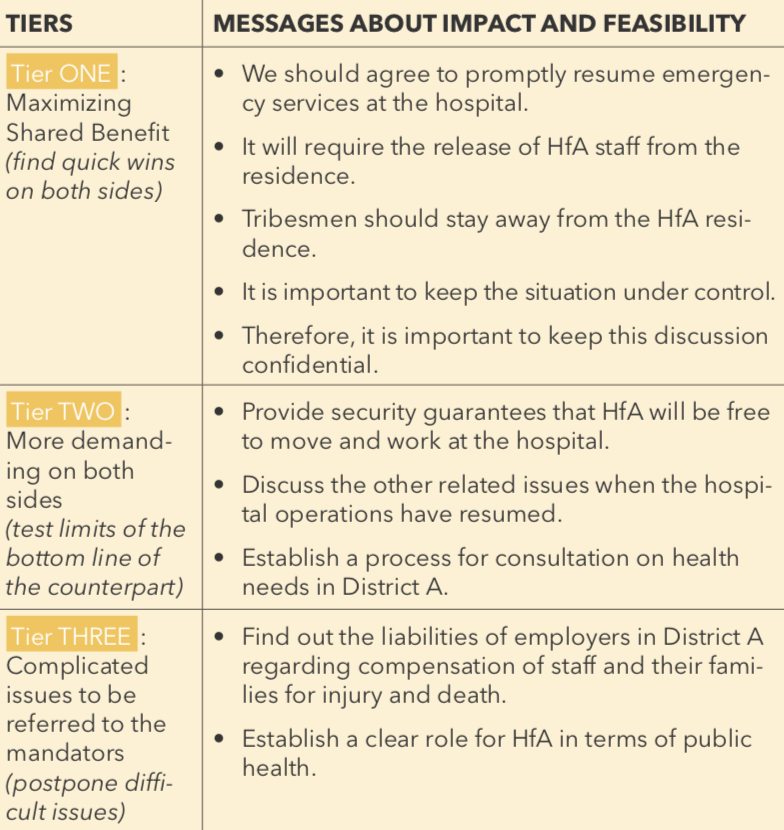

With this analysis in mind, humanitarian negotiators are in a position to consider the design of scenarios, including the angle from which they intend to approach the counterpart, and the determination of proper bottom line and red line as presented in the next module.

Concluding Remarks and Key Lessons of This Tool

This tool provides a first opportunity to observe the new role and ethos required to enter into a negotiation process. From the role of humanitarian advocate projecting humanitarian values, norms, and methods, the humanitarian negotiator must become a legitimate interlocutor to listen to the position of the counterpart, understand its tactical reasoning, and show empathy towards its values. The humanitarian negotiator needs to identify the scope of possibilities and explore alternative ways to reconcile two competing narratives. He/she must be further able to “unpack” their own organization’s values and methods to make them palatable to the counterpart and see where it is possible to find overlaps in terms of common meanings and purposes. Some of these efforts to build a rapport may exceed the mandate and red lines of the negotiator, yet there will be a time to negotiate within more constrained spaces (see the next module). At this stage, the objective is to establish the basis of a dialogue and spend the required time understanding each other’s position.

Introduction

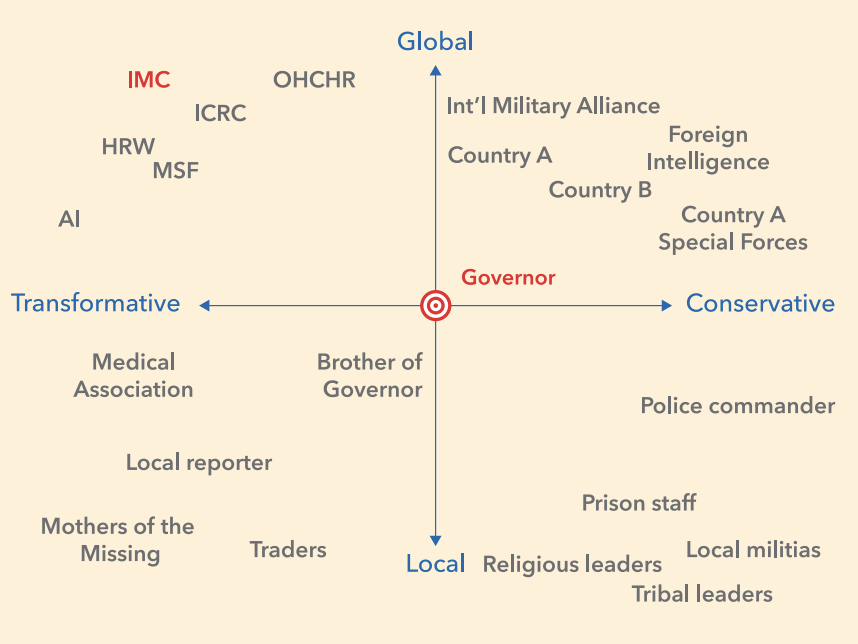

The purpose of this module is to examine the relationship between the humanitarian organization and its counterparts within the social and political context of the negotiation. The goal is to explore ways to mobilize support among influential stakeholders and create a conducive environment for the counterpart to move toward the demands and expectations of the humanitarian negotiator.

In the previous modules, we have reviewed the position, tactical reasoning, and values of counterparts. Interest and motive analyses assume a degree of autonomy of counterparts in determining their position at the negotiation table. Yet, we acknowledge that positions in a negotiation process are also influenced by the environment in which the parties evolve as much as by their tactical reasoning and the value judgments of others over the issues on the table. Values in particular are understood as a community concern and are open for deliberations within the social network of the counterparts. It is therefore important to integrate into the analysis the role and perspectives of other stakeholders in a negotiation process as a significant source of leverage (positive or negative) on the determination of the counterparts’ position.

To this end we use the model of the so-called “mapping exercise.” This exercise should be conducted in collaboration with the negotiation team, as it requires discussing the relative positioning of actors on a political map, best achieved through a critical and informed discussion among the members of the negotiation team, especially local national staff who benefit from connections with, and understanding of, social and political actors. Mapping is of particular importance in cases where counterparts play a key political role in their community (e.g., high-level government officials, tribal leaders, military commanders, etc.) and who may, in such cases, gain or lose considerable authority and legitimacy from humanitarian negotiation. Their legitimacy is intrinsically based on their ability to balance the interests of opposing political forces under their recognized leadership. It is therefore important to map out these converging or opposing influences in the counterparts’ decision-making process on a particular issue and situate the position and role of the humanitarian organization in this context.

The risk of conflating humanitarian negotiation and other political processes, including political mediation, is therefore real to the point that one cannot remain oblivious to the political footprint a humanitarian organization may bring to bear on the power relationships between the parties and their stakeholders.

Humanitarian Negotiation vs. Political Mediation

Humanitarian organizations negotiate for access and delivery in line with humanitarian principles, but must operate within the challenges of highly charged political environments. While both political mediators and humanitarian negotiators seek to stabilize a conflict situation and minimize risks of further escalation, the mission of political mediators is to build a political consensus to address the causes of the conflict, while the mission of humanitarian negotiators is to address the immediate humanitarian consequences of the conflict. Yet, pursuing humanitarian access is often misconstrued as a confidence-building tactic in the arena of political negotiations. To be recognized as impartial, neutral, and, especially, independent, humanitarian negotiators must avoid being involved in politically motivated processes. They must be equipped to play at times a political role, exerting pressure on counterparts to seek access to affected populations, while also globally mobilizing the necessary attention to ensure the effective delivery of assistance. In this context, one cannot disassociate the mobilization of political support for humanitarian action with the politicization of the same action in specific situations. It depends on humanitarian actors to remain in control of the political implications of their action.

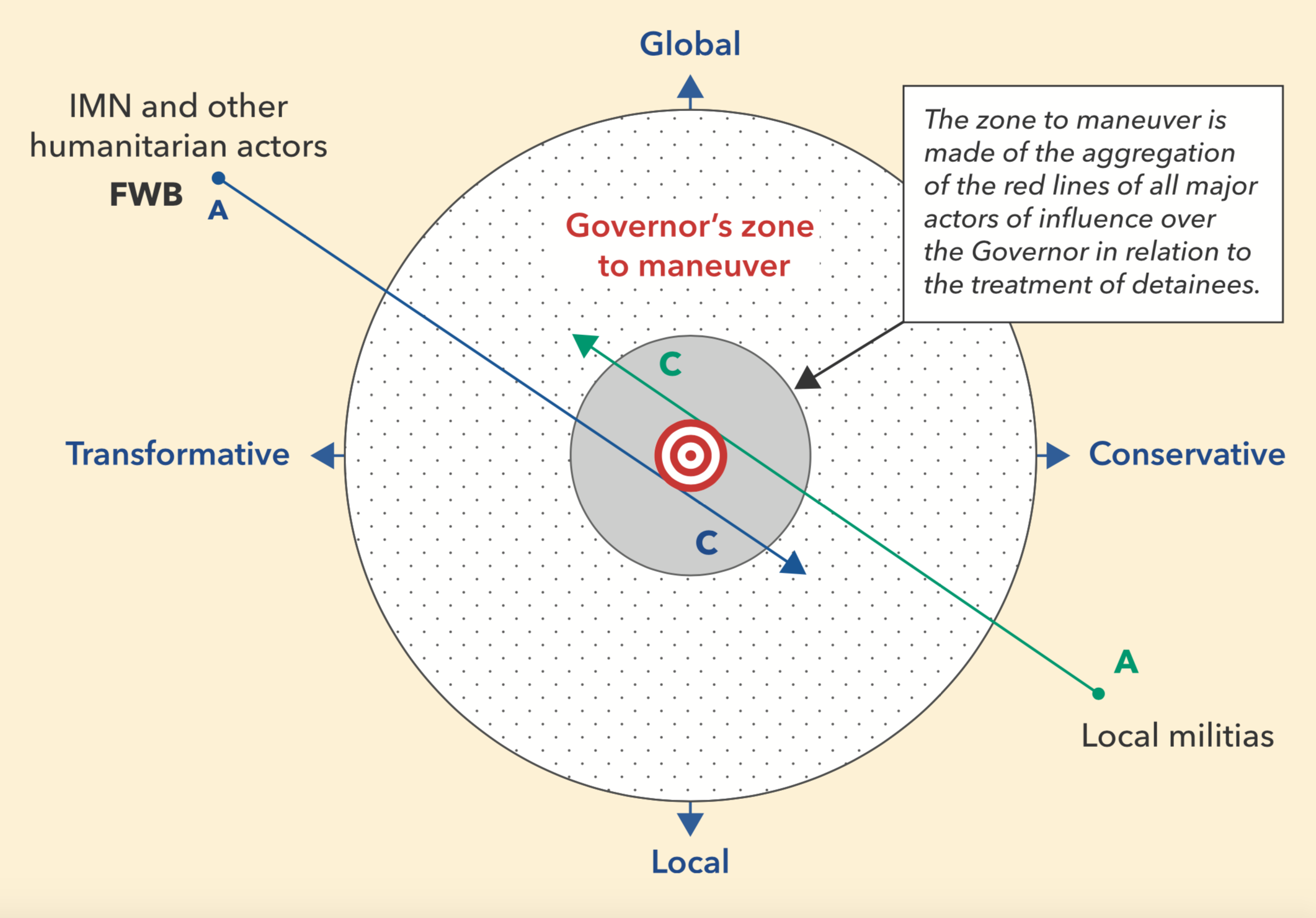

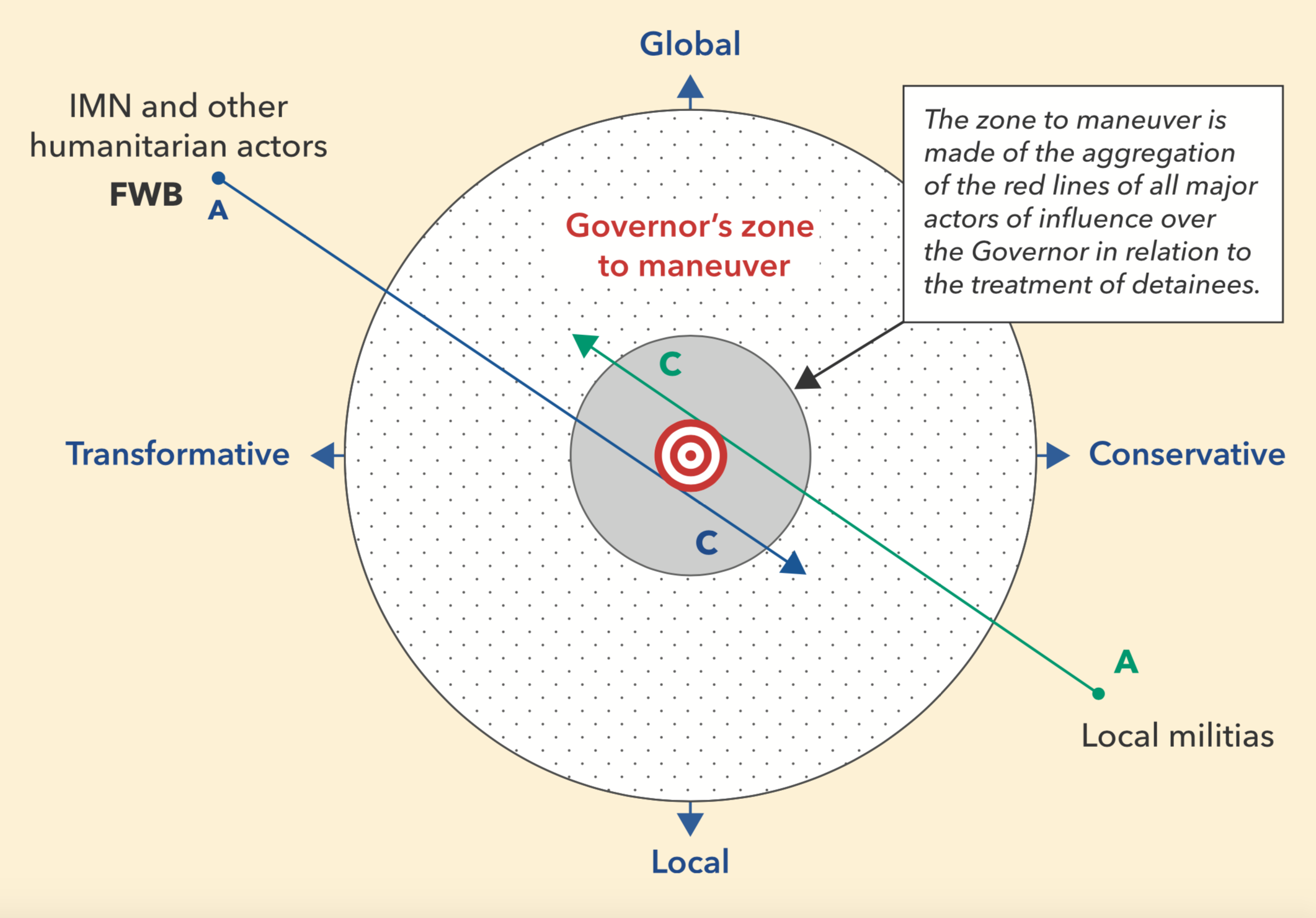

There is a growing confusion between the objects of humanitarian negotiation and the objectives of political mediation. Following the development of an integrative vision of the peacekeeping, political, and humanitarian roles of the United Nations in times of conflict, there have been increasing concerns over the use of humanitarian access and delivery as confidence-building/points of pressure with parties to hostilities. To remain neutral, humanitarian organizations need to proactively assess the political map of their intervention and ensure that humanitarian action is not being instrumentalized by other stakeholders. It is imperative that humanitarian negotiators take into account the potential costs and benefits of such relationships for the counterparts and their stakeholders.[1] To support such efforts, this module proposes a straightforward mapping tool in four steps:

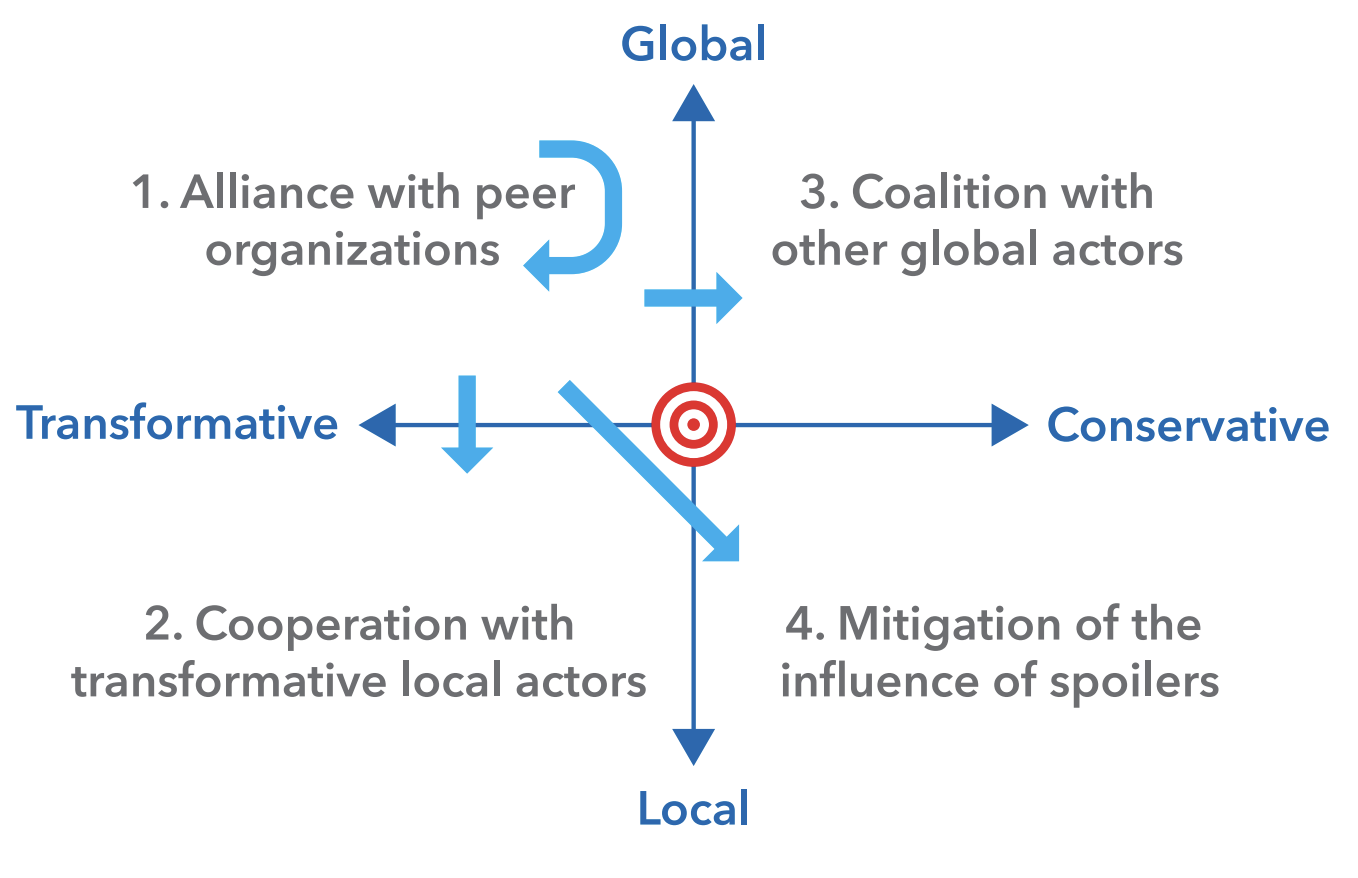

- The first step involves the creation of a mapping tool to situate the role and perspective of humanitarian organizations and stakeholders relative to each other on a specific humanitarian issue;

- The second step assigns the main counterpart the position in the center of the map and places all the relevant stakeholders in the respective quadrants across the map;

- The third step focuses on tactical schemes to guide the engagement of humanitarian negotiators with stakeholders to leverage their influence; and,

- The fourth and final step helps prioritize mobilization efforts toward conducive connections among stakeholders that may support a positive outcome of the negotiation.

Mapping influencers is not a scientific exercise. It relies on layers of subjective assessments of interactions between stakeholders. The point of a mapping exercise is not to forecast the outcome of a negotiation but rather to help plan the mobilization of the positive influence over a counterpart. While humanitarian negotiators mostly know stakeholders in their immediate vicinity who may leverage a positive influence, they are generally unaware of the second- and third-degree influencers from other quarters who may have an interest in the humanitarian agenda. Humanitarian negotiators are “small fishes in a very large pond.” The proposed mapping should help the negotiation team to have a larger perspective on the influences and trends that may help or hinder their efforts.