Resources

Digital Field Manual

Introduction

The objective of this section is to provide a set of practical tools and methods to frame and guide a humanitarian negotiation process through the design and monitoring of the mandate of the negotiator. This process is articulated around the role of the mandator who issues the mandate to the negotiator who monitors its implementation. The mandate is informed by the mission and strategic objectives of the organization. It is also delimited by the applicable rules and institutional policies governing the activities and interactions of the organization. However, the mandate is not designed to dictate specific tasks, methods, or outcomes of the negotiation but to set a genuine space of dialogue with the counterpart, providing sufficient autonomy to the negotiator in adapting the organization’s mission and goals to the reality of the field. While it provides a certain level of autonomy, the mandate should also stipulate clear red lines indicating the limits of the negotiation as informed by the institutional principles and policies of the organization.

While the word mandate is used interchangeably in the humanitarian world to define the mission of an organization, the role of a negotiator, and the responsibilities of a representative or agent of the organization, their objectives and actual use should not be confused.

The mandate of an organization refers to the overall mission and objectives of an agency granted by an external authority. This mandate may have been attributed by states as stipulated in an international treaty (e.g., for the ICRC and UNHCR) or as a decision of the UN General Assembly (e.g., for WFP and UNRWA). The mandate may also be issued by the governing assembly of a civil society organization or NGO (such as MSF, NRC, Oxfam, national NGOs, etc.) and then recognized by host and donor governments. The mandate of an organization applies to all the situations and people covered by the treaty or decision within the limits stipulated in it. The terms of the mandate are therefore fixed and can be modified formally only through the adoption of new rules by the mandator. However, organizations may show some flexibility in interpreting the terms of their mandate in evolving environments, including, at times, undertaking operations that are not stipulated in their mandate, depending on the terms of their own charter.

The mandate of a negotiator focuses on the engagement with counterparts in a specific context to fulfill the operational objectives of the organization. This mandate is granted by an internal authority, i.e., the hierarchy of the organization, for the purpose of delegating the power to engage the organization in a specific negotiation process to its representatives. The limits to the mandate are set by the mandator, are internal in nature, and can be adapted to the circumstances by the mandator. Mandates are distinct from traditional instructions given to staff in that they provide the negotiator a high-degree of autonomy to explore potential avenues for agreements, leverage influence, and seek the consent of the counterparts.

Regarding the mandate as it relates to the responsibilities of representatives of an organization and its agents (e.g., director, senior staff, head of office, spokesperson, etc.), these personnel maintain and develop relationships with external actors. They can engage the organization in discussions and transactions much like negotiators do. However, the terms of their engagement (e.g., communication line, positions, advocacy statements) are usually prepared and validated by the organization’s hierarchy. Like diplomats, agents and representatives of an organization have little room to maneuver; their role is centered on the advocacy and transmission of an institutional message regarding the position of their organization on a particular issue. They are not mandated to explore alternative avenues with the counterpart or find compromises. There may even be contradictions between the role of a representative of a humanitarian organization to defend the core values and principles of the organization and the role of a negotiator to distance him-/herself from these values in order to explore alternatives and build trust with the counterparts.

On the distribution of roles between the mandator, the negotiator, and the negotiator’s support team

There are three key actors involved in a humanitarian negotiation:

- The mandator

- The negotiator

- The negotiation support team

Each role depends on the other two to fulfill their functions properly. The role of the mandator is to govern the negotiation process:

Humanitarian negotiations are team-based, comprising the frontline negotiator who leads the engagement with the counterpart, the negotiation support team who assist in the critical reflection on the orientation of the process, and the mandator who frames the process into the institutional policies and values.

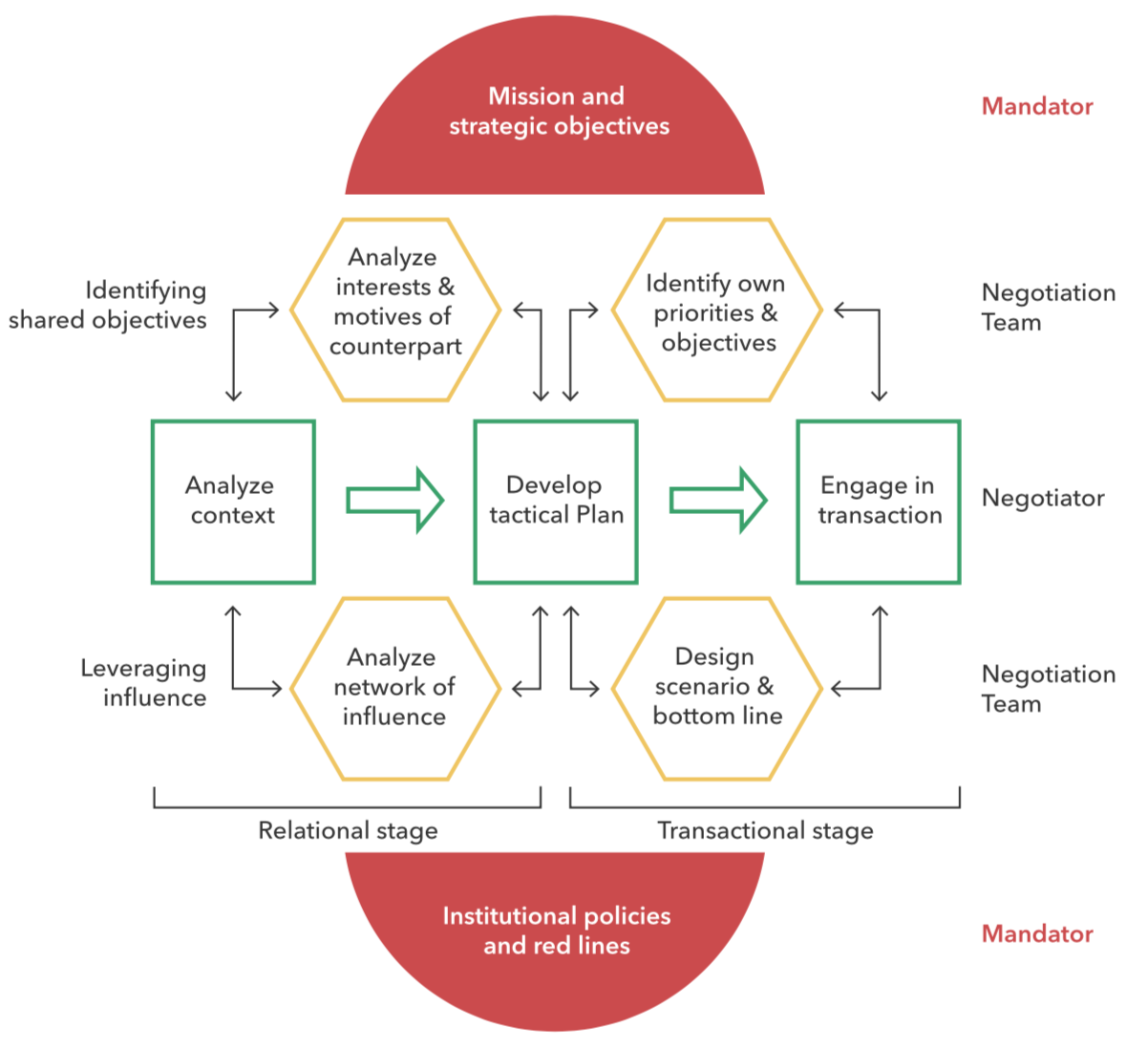

The team-effort model is an effective way for solo practitioners to maintain their autonomy as frontline negotiators while making a responsible and professional decision to open a critical collaborative space around them in the planning process of the negotiation. The deliberation within the support team aims to ensure the maintenance of the required critical space to define and regularly review the objectives of the negotiation process and inform the design of the tactical plan (see Figure 1).

The mandator provides the authority to the negotiator to represent the organization. The mandate of the negotiator can be explicit in nature, i.e., clear objectives provided, or be implicit, i.e., simply part of the job description of the staff. Usually part of the operational hierarchy of the organization, the mandator is responsible for ensuring that negotiated agreements remain within the limitations set by the institutional policies of the organization (e.g., humanitarian principles, “do no harm,” etc.). (See next modules on institutional policies.) The main tasks of the mandator are reviewed in 3 | The Negotiator’s Mandator of this Manual.

The negotiator represents the organization in the negotiation process and may come to agreements with the parties on the terms of the presence, access, and programs of the humanitarian organization. The main tasks of the negotiators are reviewed in 1 | The Frontline Negotiator of this Manual.

The negotiation support team works with the negotiator in analyzing the context, developing the tactics, and identifying the most suitable terms of an agreement to allow the implementation of these programs in a given context. The negotiator’s team plays an important role in creating a critical space where the planning of the negotiation can be discussed. This support function can be extended by mobilizing the support from peers in other organizations. The main tasks of the negotiation support team are reviewed in 2 | The Negotiator’s Support Team of this Manual.

It should be noted that humanitarian staff may be fulfilling different roles on separate negotiation processes at the same time. Hence, the head of a local office may be mandated by the country director to negotiate with the governor of the district about access to a camp while he/she may also be part of the support team of a colleague negotiating access in a different district. This same staff may also be the mandator of a local staff negotiating the provision of medical assistance to the local hospital. These three roles, as described in this Manual, encompass distinct responsibilities and interactions.

To help define the role of the mandator, this section will review, in turn, the identification of the strategic objective of the negotiation as well as the cost/benefit of the institutional policies, both elements framing the negotiation process through the mandate and the relationship with the mandator.

Introduction

The purpose of this module is to draw the key elements of the mission and strategic objectives of the organization to inform the elaboration of the negotiator’s mandate in a given context. It concludes with a framework to plan external communication around the negotiation process.

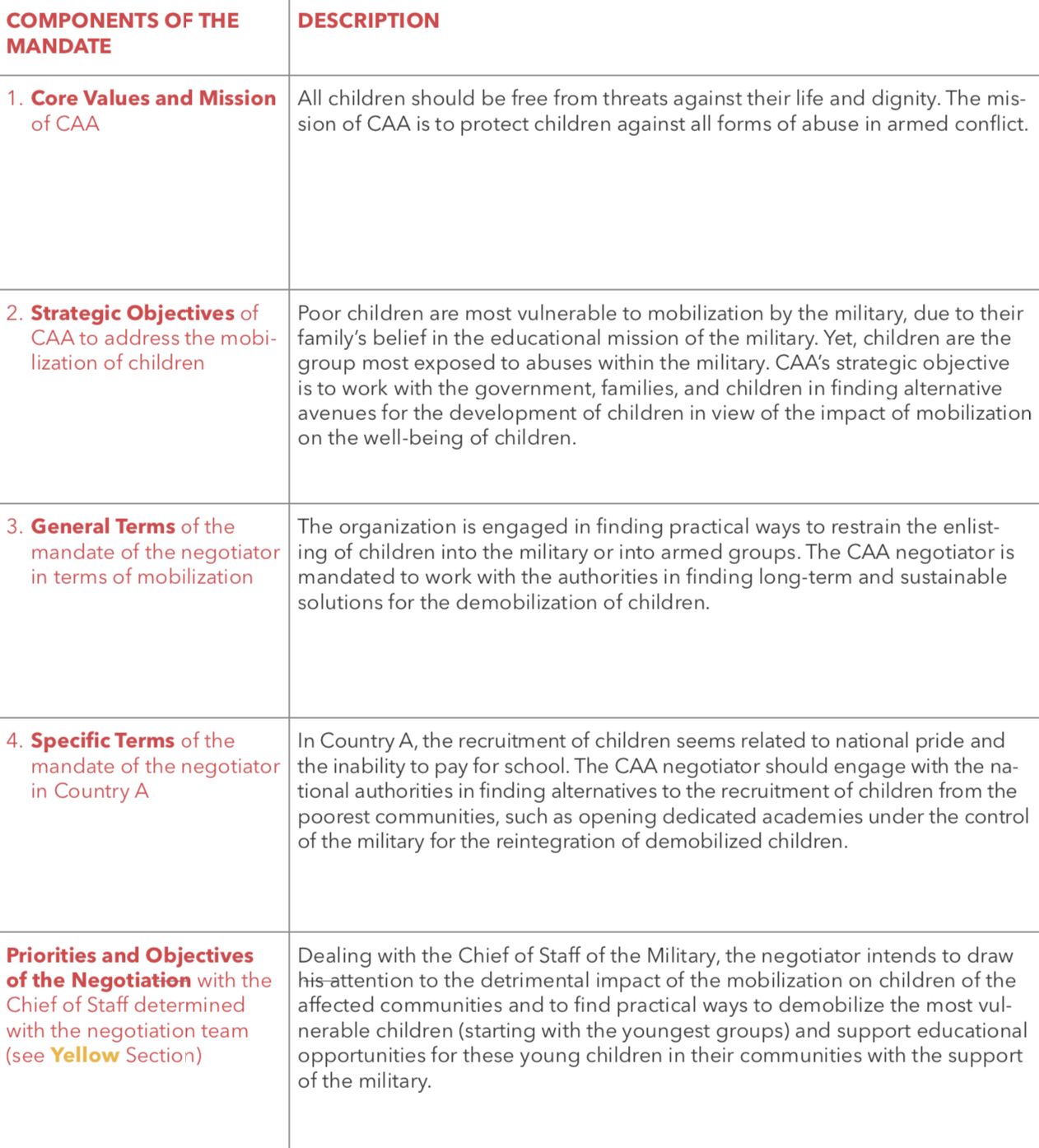

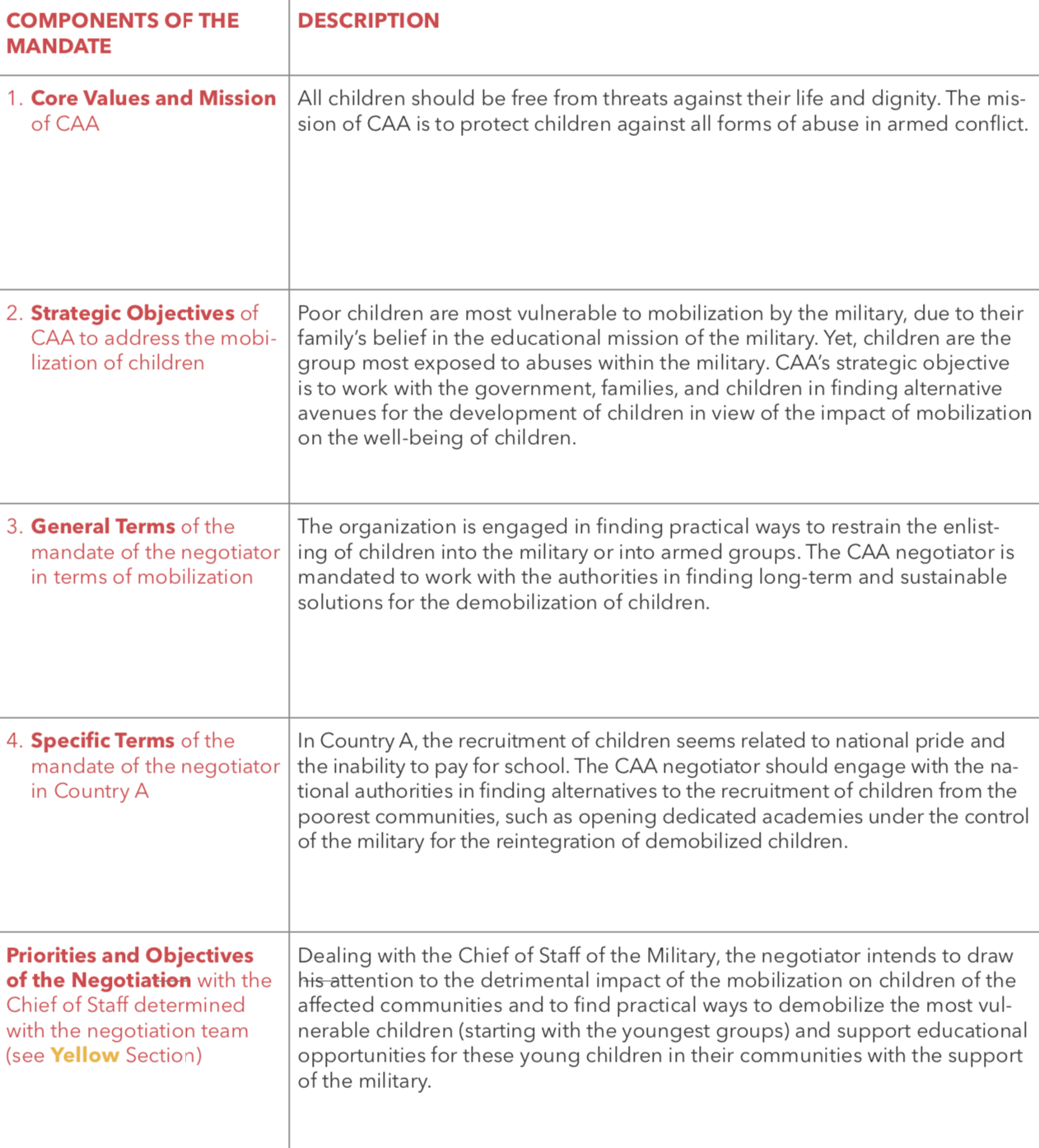

The mandate of a negotiator is composed of:

General terms involving a well-defined understanding of the mission and strategic objectives of the organization;

Specific terms involving the operational objectives of the organization in the given context as well as policies and red lines delineating the mandate of the negotiator; and,

A delegation of authority from the hierarchy of the organization to the negotiator to engage with the relevant authorities or groups and seek their consent or support in these operations.

In this sense, the mandate provides a framework of reference for the negotiator and the negotiation team to identify the priorities and objectives of a negotiation process as well as design the required scenarios and bottom lines. The terms of the mandate should be sufficiently broad so as to allow a space of interpretation facilitating the adaptation of the strategic objectives of the organization to the reality of the operations. At the same time, it must be reasonably detailed to ensure the alignment of the negotiation plan with the core values and norms of the organization.

The clearer the mandate of the negotiator, the more able the negotiator will be to build a trustful relationship with the counterparts and to find practical solutions.

General terms of the mandate

Field practitioners recognize that the strength of humanitarian negotiators is directly connected to the clarity of their mission and the strategic objectives of their organization. The clearer the mandate, the stronger the leverage the negotiator will have in the dialogue with the counterpart. Conversely, if the mission and strategic objectives of the organization are vague or uncertain, it will be difficult to build the necessary trust and explain the rationale under which the counterpart should be persuaded to engage and make compromises. The mandate is therefore a critical asset for the negotiator to make a clear case in the negotiation process. The responsibility of clarifying the strategic objectives of the negotiator is with the operational hierarchy of the organization.

Specific terms of the mandate

While the general terms of the mandate are applicable to a number of situations encountered by the organization, the negotiations are issue- and context-specific, i.e., they require negotiating arrangements to address specific needs under the control of selected counterparts within a given context. The specific terms of the mandate are generally considered to be confidential between the mandator and the negotiator, and already include a selection of operational objectives and identify areas of potential compromises, taking into account the potential cost and reputational risks. These terms are stipulated to frame the conversation between the negotiator and the counterpart, not the final terms of the agreement. They should remain privileged information between the mandator and the mandatee (the negotiator). The specific terms of the mandate may be very close or at times identical to the priorities and objectives identified by the negotiator and his/her team in a specific negotiation process (see Section 2 YELLOW). They may also be quite different, depending on the context, the common shared space with the counterparts, and the red lines of each side.

Building on an example related to the mobilization of children, the mandate of the negotiator of Children Above All (CAA), an international NGO devoted to the protection of children in conflict, may look like this:

A delegation of authority

The third and most important aspect of the mandate is the delegation of authority from the mandator to the negotiator to represent the organization and ultimately agree on the terms of the transaction with the counterpart.

This delegation of authority is an essential part of the mandate which puts the relationship between the mandator and the mandatee on a different level compared to a regular representative or staff person. It is important to distinguish here instructions to represent the position of an organization (e.g., in an advocacy role) from a mandate to negotiate for an organization. The former focuses on the values and norms of the organization and trying to lobby for their implementation. The latter concerns the ability to make compromises that will benefit both parties to the negotiation. Some organizations may be inclined to avoid making a distinction between the functions of a representative and the functions of a negotiator as it allows them to remain vague on the type of compromises the organization is ready to accept. They will expect their agent to find “practical solutions” at the field level without specifying institutional red lines (e.g., on issues of distributing assistance to the parties in control of a population, or when an organization is to accept a military escort). At times, organizations will not require that the agent report to their hierarchy on the details of the solutions found at the field level that may contravene institutional policies. The policy of “don’t ask, don’t tell” offers the largest flexibility to trusted negotiators in the field. It also carries significant reputational risks in an interconnected world. What happens in the deep field rarely stays there very long. Furthermore, keeping some of these arrangements secret within the organizations prevents the normal learning process of the organizations and the testing of their core values and norms in reality. “Don’t ask, don’t tell” enables the creation of various levels of misperception within the hierarchy and governance of the organization about the relevance and practical nature of the core values and mission of the organizations, which, sooner or later, will have to come to terms with reality.

Regulating negotiation processes through proper mandates and ensuring a minimum of internal transparency on the compromises allowed may at first put into question the interpretation of some of the humanitarian principles of the organization and result in greater risk avoidance at the field level. In the long run, it will probably ensure greater cohesion in the negotiation and elevate the standing and professional reputation of organizations operating on the frontlines.

Application of the Tool

This segment presents a set of practical steps to develop and interpret the mandate of a negotiator. There are three steps elaborating a mandate, either formal (explicit) or informal in essence as part of the job description of the staff member in the field.

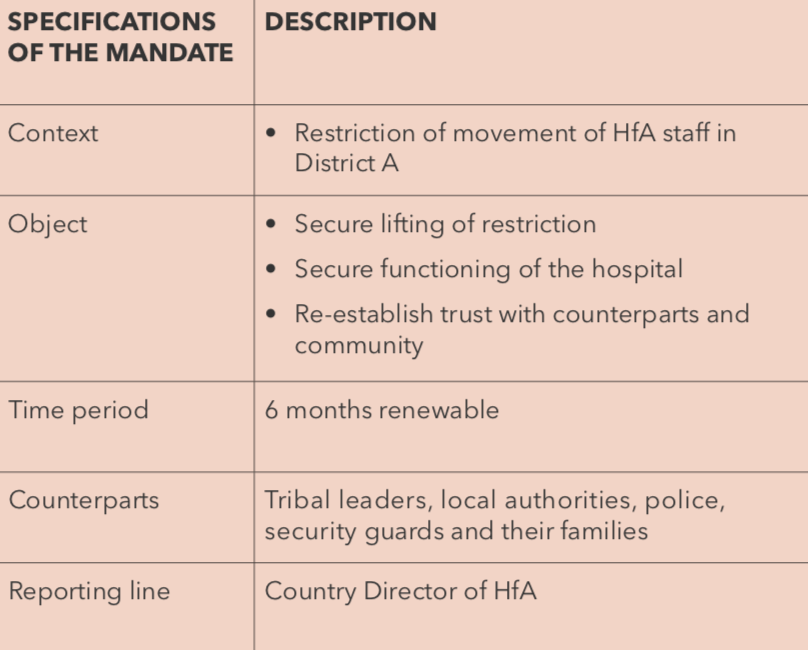

Step 1: Stipulate the location, object, and time frame of the mandate

At the point of departure, the mandate must indicate the location, object, and time frame of the capacity of the humanitarian professionals to negotiate in the name of the sending organization. This mandate is often contained in the job description and professional title of the humanitarian professional (e.g., head of the mission to Country A, head of operation in District B, representatives of SCF to Country A). At other times, the negotiation mandate will be communicated in terms of the mission of a negotiation team.

Drawing from the cases presented in the modules of 2 | The Negotiator’s Support Team, one may consider the following case.

Example

Health for All’s Surgical Team Retained in a Labor Dispute

Nine staff members of Health for All (HfA), an international health NGO, have been prohibited by tribesmen from leaving their residence in District A for almost a week following a disagreement between HfA and the guards of the local HfA hospital. This dispute follows HfA’s plans to close the hospital due to decreasing war surgery needs in the region. The guards, who belong to an important tribe in the region, claim that the hospital should remain open and their compensation be paid as there are still considerable emergency health needs in the region. The guards, supported by tribal representatives, further argue that they put their lives at risk for several years to maintain the access of patients and staff to the hospital during an especially violent conflict. Some of the guards even lost their life in this process and others sustained long-term disabilities. Families of the guards wounded or killed during the conflict further request long-term monetary compensation for the loss of income before HfA pulls out of District A.

For now, the hospital is barely operational, with several emergency needs left unattended. The tribal leaders have agreed to meet with HfA representatives to look for a solution. The government has refrained from intervening in what they see as a private labor dispute. The army and police have only a limited presence and control over the situation in District A and would not intervene without the support of the tribal chiefs.

Health for All has decided to enter into a negotiation process with the tribal leaders. Rather than asking the HfA representatives to District A to “figure things out,” senior managers of HfA have decided to draw a proper mandate for HfA experienced negotiators to engage in this delicate process. In such a situation, the mandate will specify:

Negotiators must receive clear instructions on the expected format, timing, and content of the reporting mechanism to their mandator and/or operational hierarchy regarding the negotiation process. Instructions should also discuss the bottom lines of the dialogue, i.e., moments where the negotiator will need to go back to the mandator to report and discuss further opportunities in terms of agreement. This reporting should optimally integrate the results of the analytical tools provided to the negotiation team of HfA (see 2 | The Negotiator’s Support Team), as well as the relevant information on the context analysis and the proposed tactics of the negotiation.

Step 2: Stipulate the person in charge of the negotiation

The second aspect is to identify the representative of the organization at the negotiation table and ensure that this person will have the time and resources needed to undertake the negotiation.

In our case, HfA may decide to:

- Appoint the head of the regional office as the lead negotiator with the tribal leader.

- Release the person from other administrative functions for the duration of the negotiation process.

- Support the creation of a small team of colleagues and peer reviewers to accompany the lead negotiator.

- Give the lead negotiator the benefit of the support of the local HfA office in terms of security, transport, and translation, as required by the negotiation team.

Step 3: Stipulate the general and specific terms of the mandate in the objectives of the negotiation

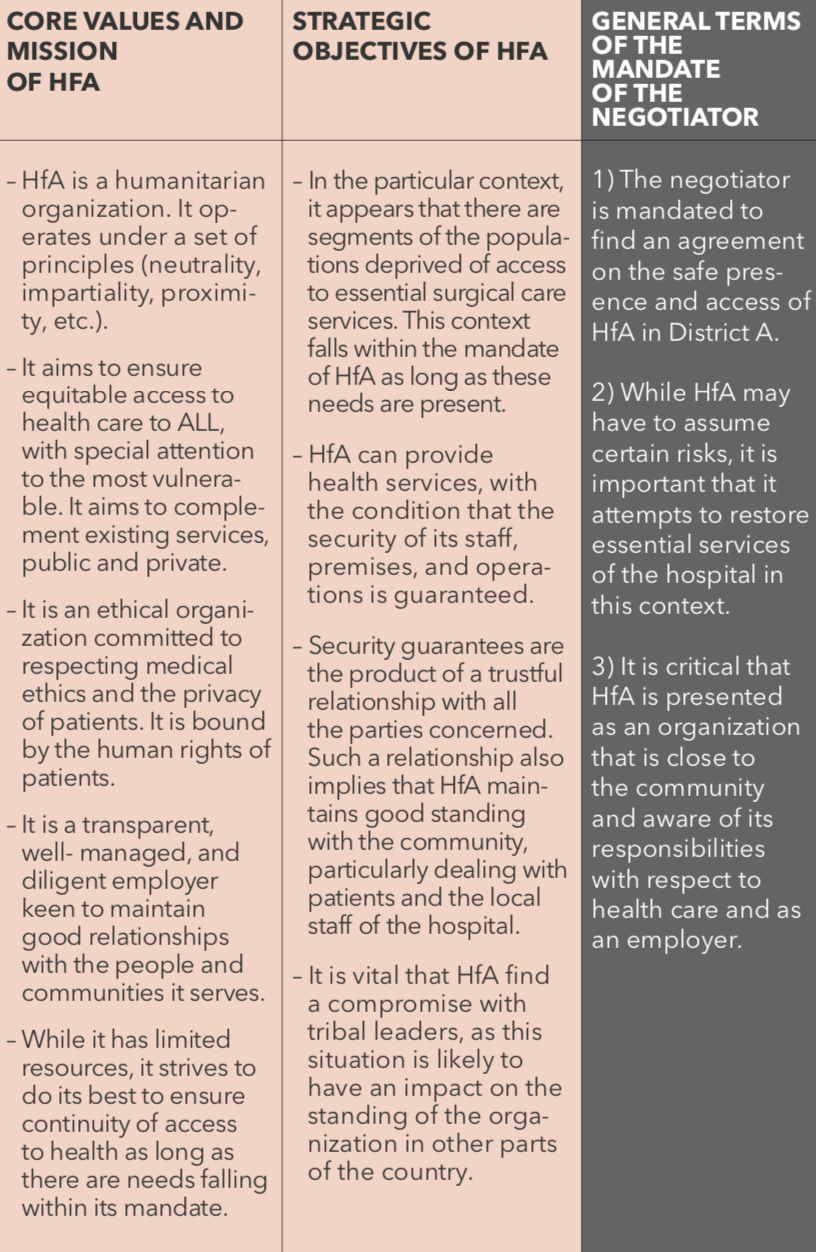

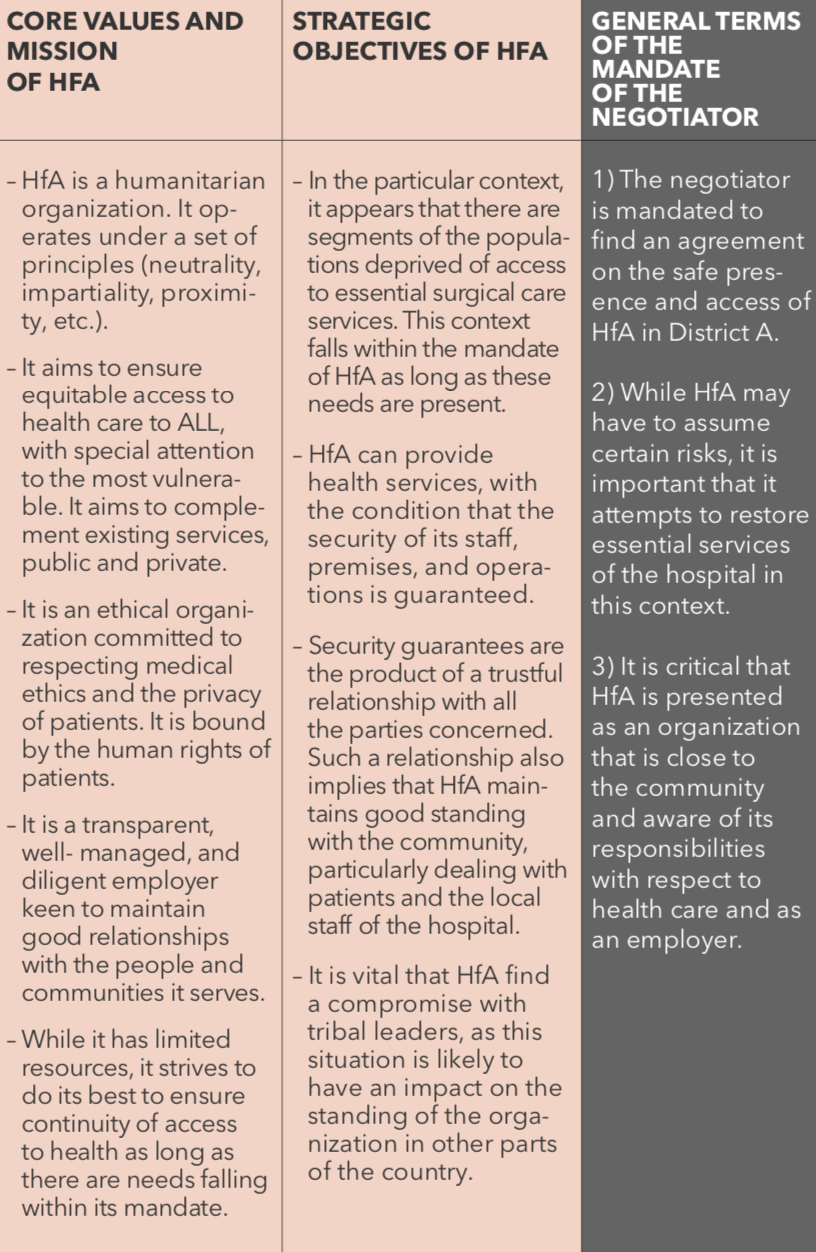

The general terms of the mandate are informed by the mission of HfA as well as by the professional standards, as presented in the module on Identify Priorities and Objectives of the Negotiation in Section 2 YELLOW.

General terms of the mandate

Specific terms of the mandate: Responding to the needs arising in District A

The specific terms of the negotiation relate to the issue at stake, either factual or normative in essence.

- A disagreement on facts will necessitate a mandate for a factual negotiation supported by operational experts and technicians of the organization and building up the required evidence of the negotiation to succeed.

- A divergence on norms will call for a mandate to conduct a normative negotiation mobilizing the support of the professional and political community in the context to engage on the normative framework of HfA. (For more information on this distinction, see the module The Island of Agreement in the GREEN Section of this Manual.)

In this particular case, the mandate is triggered by the restrictions imposed on the movement of HfA staff by the tribal leaders and the untimely announcement of the closure of the surgical hospital. There seems to be no disagreement on the facts (there are no questions about the facts that staff members are retained and there are growing needs at the hospital). The negotiation will essentially be normative in terms of the obligations of the parties regarding the security of staff and the diligence of HfA in terms of management of the only tertiary medical service available in District A. (For more details on normative negotiation, see Section 1 GREEN Drawing a Pathway of a Normative Negotiation.) These specific terms will provide a framework for the elaboration of specific objectives of the negotiation (P) discussed in Section 2 YELLOW Module 2: Identifying Own Priorities and Objectives at the negotiation table. These terms are considered to be part of a confidential relationship between the mandator and the negotiator and his/her team.

Specific terms of the mandate (Strictly Confidential)

Concluding Remarks and Key Lessons of This Tool

This segment provides a straightforward tool for the elaboration of the mandate of the negotiator. The tool is designed for the mandator, i.e., the hierarchy of the negotiator, to frame the role of the negotiator in the proper strategic objectives and institutional policies of the organization. It is understood that the clearer the mandate, the stronger the leverage the negotiator will have in the dialogue with the counterpart.

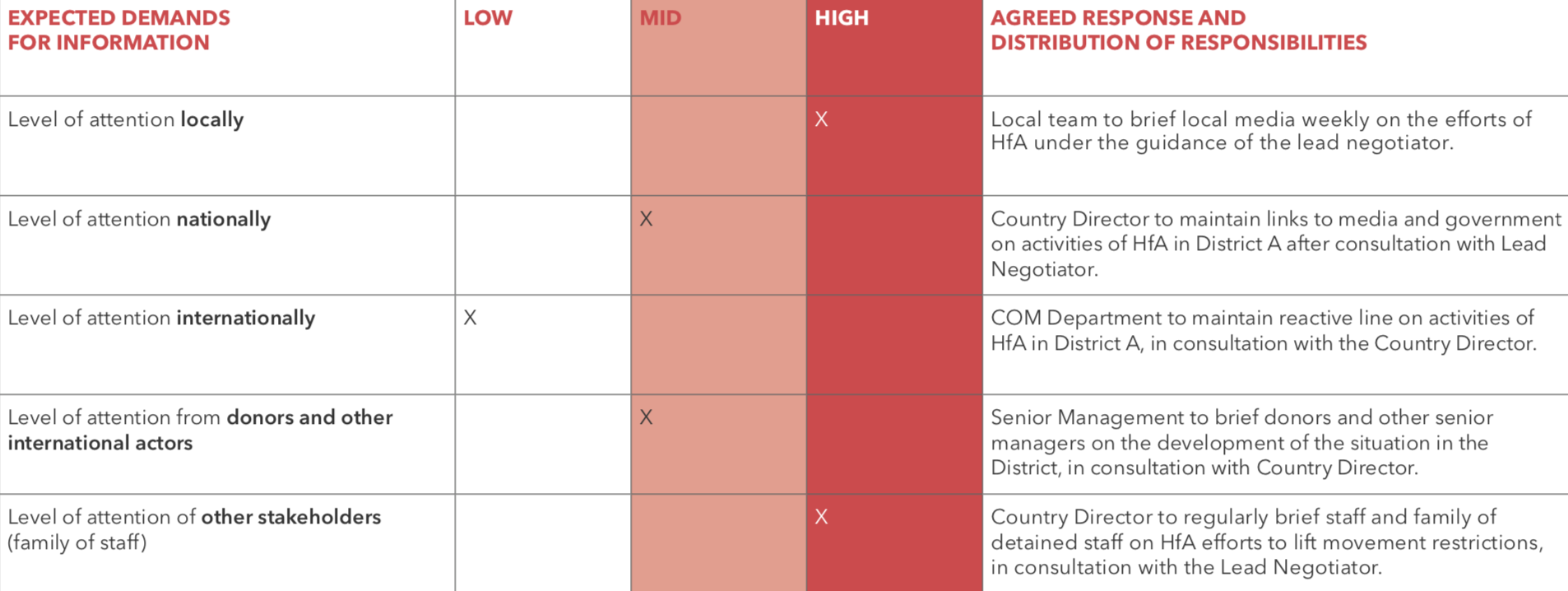

Regarding external communication, a critical point will be to ensure the confidentiality of the negotiation process and monitor as much as possible information about the situation. While information on the negotiation process is expected to circulate, it will be important to prepare a series of information briefings on the negotiation process as required by the circumstances and equip the country and negotiation team with resources in terms of public communication. It is vital that the lead negotiator remain in control of the communication on the negotiation process at the local level, even coming from HQ, as such communication may have severe consequences on the trust and expectations of the parties. Any information coming out of HQ is part of the information impacting the negotiation process at the local level, and in our current media environment, every bit of local information may go global in a matter of hours. The communication department that has legitimate interests in communicating about the activities of HfA must be integrated into the chain of the negotiation so as to understand its logic and the implications of its communication at the operational level, particularly in a tense negotiation where even the life of the frontline negotiator may be at risk.

As a first step, the mandator should ensure that the organization has a clear message to disseminate about the activities of his/her organization in the specific context and, if necessary, the ongoing negotiation, as this message will be read attentively by all the stakeholders. The message should be made as much as possible of uncontested facts and convergent norms in order to build on the tactical plan of the negotiator (see 2 | Tool 2: Drawing the Island of Agreements). This message should also be articulated on the same grounds as the iceberg analysis of the position of the organization (see 2 | Module B: Identifying Own Priorities and Objectives), namely:

The clearer the mandate of the negotiator, the more able the negotiator will be to build a trustful relationship with the counterparts and to find practical solutions.

As a first step, the mandator should ensure that the organization has a clear message to disseminate about the activities of his/her organization in the specific context and, if necessary, the ongoing negotiation, as this message will be read attentively by all the stakeholders. The message should be made as much as possible of uncontested facts and convergent norms in order to build on the tactical plan of the negotiator (see 1 | Tool 2: Drawing the Island of Agreements). This message should also be articulated on the same grounds as the iceberg analysis of the position of the organization (see 2 | Module B: Identifying Your Own Priorities and Objectives), namely:

- WHY does our organization hope to operate in the particular context? What are our inner principles, motives, and values? What are the needs justifying this operation?

- HOW does our organization operate? What problems are we trying to address? What professional tools will we use and what methods do we plan to implement? What are the difficulties encountered?

- As a result, WHAT is our position in the particular negotiation? What is our offer of service? What are the terms under which the organization is ready to operate as a point of departure of the negotiation (i.e., best-case scenario of an agreement)?

Drawing from the analysis of the iceberg of the organization, in this case HfA, the external communication briefing would look like this:

ELEMENTS OF COMMUNICATION

WHO is HfA? What values define HfA as a humanitarian organization?

WHY does HfA want to operate in this context?

DESCRIPTION

Core mission

The mission and identity of HfA are predicated on several elements that are of relevance in this particular context:

- HfA is a humanitarian organization. It operates under a set of principles detailed in its mission statement (neutrality, impartiality, proximity, etc.).

- It aims to ensure equitable access to health care for ALL, with special attention to the surgical needs of the most vulnerable in District A. It aims to complement existing services, public and private.

- It is an ethical organization committed to respecting medical ethics and the privacy of the patient. It is bound by the human rights of patients.

- It is a non-profit organization providing free services to populations in need of health care.

- It is transparent, well managed, and a diligent employer looking to maintain good relationships with the people and communities it serves.

- While it has limited resources, it strives to do its best to ensure the continuity of access to health care as long as there are needs falling within its mandate.

In the particular context, it appears that there are segments of the population deprived of access to essential health care services. This context falls within the mandate of HfA as long as these needs are present.

ELEMENTS OF COMMUNICATION

WHAT does HfA want out of this negotiation? What is HfA’s position? How does it want to communicate this position?

DESCRIPTION

Regarding the Negotiation

- HfA insists on the immediate release of all HfA staff and their evacuation from District A.

- Tribal leaders must guarantee the safety and well-being of HfA staff in the meantime.

- HfA scales down its surgical activities in the region and hands over the hospital to a third party, including obligations towards the guards and their families.

- Meanwhile, HfA engages in consultation to rebuild trust with the community.

ELEMENTS OF COMMUNICATION

HOW does HfA operate? What are the specific methods?

DESCRIPTION

How HfA works

- HfA is a professional organization. It maintains professionally recognized protocols in terms of medical services, managerial methods, and financial accountability to donors.

- It maintains a dialogue with the community and local health professionals around assessing the needs of the population.

- As a private charitable organization, HfA has the authority to decide on its priorities and objectives. It regularly consults with local leaders and communities on the development of its activities.

- It is also accountable to the health authorities of District A in terms of its role and objectives in the health care system of the district.

- In terms of security of staff and premises, it hires guards from the community to help secure the premises (hospital, clinics, residence of staff) in line with applicable legislation and local customs. The guards are lightly armed due to the high level of armed and criminal violence in the context.

- A direct link is maintained between HfA guards and the local police force.

- In view of the tribal character of the society, the selection of the guards is made in consultation with tribal leaders who will propose and review candidates.

Communication roles should be carefully reviewed and assigned so as to ensure proper internal control over the messaging of the organization. As mentioned above, messages coming from any part of the organization are inherently part of the negotiation process.

Therefore, the mandator should be attentive to the attribution of responsibilities in communication on a negotiation process:

In our case, HfA may decide:

- To instruct the negotiator and negotiation team to report on a weekly or biweekly basis on the progress of the negotiation;

- To work with the negotiation team on an external communication strategy;

- To prepare with the negotiator a series of pro forma communication lines on the negotiation process; and

- To inform its communication department that all communications must be cleared by the negotiation team. This is essential so that the negotiator, who is responsible for creating and maintaining the relationship with the counterpart, is not surprised by any communications and has the opportunity to inform counterparts in advance.

Concluding Remarks and Key Lessons of This Tool

This segment draws on some proposed tools to manage the communication environment of the negotiation in order to preserve the privileged relationships with the counterparts and stakeholders as well as to maintain a degree of responsiveness to external inquiries so as to manage the public profile of the process.

Introduction

The purpose of this module is to identify the sources of institutional policies of an organization, providing a framework to guide a negotiation process and set up the necessary red lines.

Red lines are an essential part of the mandate given to a negotiator. They set the limits under which the negotiator is authorized by the mandator to discuss the terms of an agreement between the organization and the counterparts. While they may appear to confine the role of the negotiator by imposing predefined boundaries, they represent a critical feature of the mandate by plotting the actual scope of possibilities from the ideal outcome to the red line of the mandate. There cannot be a mandate to negotiate an arrangement without some minimal limits to clarify where the organization would be unwilling to compromise.

Red lines should be understood more as enablers rather than actual limits of a negotiation process, recognizing the space of the negotiation granted to the negotiator and the negotiation team.

The determination of the red lines should always stay within the domain of the mandator and never be under the control of the negotiator. There’s good reason for this: at the moment a negotiator starts to steer the red lines of his/her mandate, the construct of the mandate falls apart and the negotiator becomes directly exposed to the political pressure of the counterparts and social pressure of the environment. The role of the humanitarian negotiator on the frontlines is to mediate between the parties to find a pragmatic solution within the red lines.

On the Origins of Red Lines

Red lines are the product of internal policy deliberations informed by principles and norms drawn from external sources (e.g., humanitarian principles, professional standards, moral values, etc.). As with the objectives of the negotiation, there are several layers of red lines. Generic red lines exemplify some of the core values of a humanitarian organization. Specific red lines are particular limitations applied to a given context, theme, or process. One can therefore list these red lines based on the relevant institutional policies and normative sources. The objective of this module is to clarify the sources of red lines and how institutional policies can be used in framing a negotiation process.

As mentioned in 2 | Module 4: Drawing Scenarios & Bottom Lines, the scope of the conversation with the counterparts ranges between ideal outcomes, bottom lines, and red lines. Ideal outcomes relate to the most principled positions that maximize the benefit of the humanitarian organization; bottom lines are a tactical positioning of the negotiator to determine the limits of the open dialogue; and red lines are the hard limits of the mandate, i.e., the points beyond which negotiators are unable to agree on the terms of an operation.

Tool 17: Identification of Red Lines

There are various sources of limitations involved in setting red lines:

- Legal red lines,

- Institutional red lines,

- Professional red lines, and

- Moral or ethical red lines.

Legal Red Lines

While humanitarian operations may take place in areas with a limited legal order due to the conflict environment, humanitarian organizations are not operating in a legal vacuum. Humanitarian organizations remain subject to multiple jurisdictions and laws, such as:

- Community norms of the region;

- National laws of the state of operation;

- National laws of the state of incorporation of the organization (in the case of NGOs);

- National laws of donor states;

- National laws of states of transit as well as procurement of goods, services, and employment;

- National laws of states hosting the financial institutions serving the organizations; and

- International laws and regulations such as UN Charter, IHL, HR, counterterrorism legislation, etc.

These multilayered jurisdictions play a role in regulating frontline negotiations, as observed over the recent years in terms of counterterrorism legislation. There can be many legal considerations; though not a complete review, the following are some legal red lines mandators and negotiators should be aware of as they consider options.

Community norms

Community norms are legal red lines that must be respected by individuals and social actors operating in a given community. These norms are customary as their normative character resides in the shared belief within the community that the expected behavior is compulsory. Customary norms can be found in written texts but are usually part of an oral tradition detailing local habits, religious restrictions, or other social norms that have the force of law within the community hosting an operation. While their form remains quite vague and hard to predict for outsiders, community norms are understood by frontline negotiators as an important source of directions and prohibitions. They recognize that the presence and action of a humanitarian organization in a given community may be highly disruptive, challenging its traditional social and political order and running against a number of community norms. Compared to national laws and other sources of positive laws, community norms are often enforced by the community itself without much due process. Such expediency may have direct and unexpected consequences on the humanitarian operation and staff that are subject to community norms. As a result, humanitarian negotiators are well advised to ensure that the proposed operations fall as much as possible within community norms. Consideration of community norms, pre-emptively and proactively, can be critical in building trust and fostering acceptance and a positive relationship that can contribute to future negotiations. For example:

Example

Community Norms Restricting the Delivery of Food Assistance

Food without Borders (FWB) has received a consignment of MREs (Meals Ready-to-Eat) from a Europe-based multinational military contingent to distribute to refugees in a camp in Country A. The refugee population in the camp is from a religious minority originating from Country B. FWB notes that the MREs coming from Europe contain pork. While there is no legal restriction in Country A prohibiting the importation and consumption of pork, the distribution and consumption of pork within the refugee community are prohibited under local community norms. This customary norm constitutes a red line for the FWB negotiator in the negotiation with refugee representatives as FWB is not allowed to violate community norms.

National and international legal norms

Legal norms are rules that regulate the behavior of individuals and social actors under the jurisdiction of the legal authority that has adopted these rules. There can be local laws (e.g., rules pertaining to the routing of convoys in a municipality), national laws (e.g., rules pertaining to food standards, security restrictions, taxation, etc.), and international laws as recognized by the national authority that regulates the behavior of national and international actors within the country. Some legal norms may also originate from customary standards or a religious order (e.g., Sharia Law), becoming codified or otherwise integrated into the national legal system. Local, national, and international norms apply to all humanitarian actors operating within the jurisdiction of the country.

A humanitarian organization may benefit from exceptions under some of these rules or may have been granted an immunity of jurisdiction. If there is immunity of jurisdiction, this is specified in national laws and a legally binding document (e.g., a headquarters agreement) or international treaties (e.g., Convention on the Privileges and Immunities of the United Nations). International law is not directly applicable to a jurisdiction without the national government being party to the treaty or having otherwise agreed to respect its provision. For example:

Example

Food Without Borders Draws on International Law to Request Access to Refugee Populations Hosted by Country A

Food without Borders (FWB) is contracted by UNHCR to provide food assistance to refugees in Country A. FWB claims that it has a right of access to a refugee camp based on the obligation of the state to provide food assistance to the refugees under the 1951 Refugee Convention, as well as the Geneva Conventions that provide for a right of access to civilians in need under the ICRC Customary Law Study. It further claims that globally accepted humanitarian principles require that the government of Country A does not interfere in the provision of impartial and neutral assistance. FWB also insists that humanitarian action be exempted from any taxation by local authorities on the import of food rations. It argues that these taxes contravene both the fiscal immunity of the UN agency that contracted with FWB and the diplomatic immunity of the donor that funded the project.

Unfortunately, the counterpart, who is also a legal professional, denies all the claims, arguing:

- Country A has not ratified the 1951 Refugee Convention. It is therefore not obligated under this treaty. UNHCR can still refer to its role and mandate described in the Convention, but it does not imply a legal obligation of the government of Country A. This reference does not apply to FWB as a contracted entity.

- While IHL applies to the conflict situation in Country A, it does not provide for a right of access to FWB. The ICRC Study is not a legally binding document. It provides only an expert opinion of the ICRC on what it sees as customary law in IHL.

- Humanitarian principles as defined in UN General Assembly Resolution 46/182 require the consent, if not active request, of the host state for any humanitarian operation to take place on its territory in line with its obligation under IHL. FWB cannot argue it has a right of access under humanitarian principles.

- Finally, if the UN Convention on Privileges and Immunities and the Vienna Treaty on Diplomatic Relations are in force in Country A, they apply respectively only to the UNHCR and the government donor, and not to FWB. Therefore, local tax regulations are applicable to the assistance of FWB.

In addition to these points, the counterpart asserts that counterterrorism legislation prohibits any form of material support to listed terrorist organizations in Country A based on the national legislation and in line with international rules and decisions. Therefore, FWB is accountable to prevent food assistance from being delivered to members of the listed armed group Alpha hiding among refugees. Failure to comply with counterterrorism rules of Country A may engage the legal liability of FWB for material support to a terrorist group as well as the criminal responsibility of its staff.

At the negotiation table, legal norms are often used to frame the options of what is considered to be legal or illegal by the government counterpart. One should recognize that these legal norms have been crafted by governments. They rarely favor humanitarian organizations over the freedom of government. Yet, the humanitarian negotiators may also use such legal restrictions framing their own red lines when the discussion involves illegal or criminal acts under the national law of the country of operation, the laws of the country of the donor, or the laws of the country of origins of the organization. For example:

Example

The Governor of District A Seeks Financial Advantages from FWB to Allow Access to Refugees

In the same case mentioned above, a close friend of the Governor informs FWB representatives that:

- To accelerate the delivery of the required transport permits from the Governor’s Office, an exceptional informal (i.e., undocumented) “security” fee of USD 500 per truck is required to allow the convoy to enter into the camp. This fee is payable in cash to a friend of the Governor.

- The only transport company allowed in the camp is owned by the wife of the Governor.

- Police officers in the camp must be hired by FWB at a significant rate to facilitate access to the camp.

- A local security officer of the Governor requires the names and addresses of the female local staff of FWB active in the country. Information circulates that members of the security force regularly harass local female staff of INGOs in exchange for allowing them to work for the INGOs.

FWB representatives who have been briefed on the legal obligations of FWB in Country A dispute these restrictions, claiming that:

- There is no legal basis for the payment of a security fee per truck. FWB is concerned that such payment is perceived as a violation of anti-corruption legislation in Country A. FWB is bound by the laws of Country A.

- The contract with the foreign donor subjects FWB to the laws of the donor government. These laws require a properly documented and audited legal tender process for hiring a truck company. FWB is not able to accept the monopoly of the truck company accessing the camp.

- The role of police officers under the law of Country A is to ensure law and order. Providing food assistance is part of the public services of Country A. There is no law that requires the payment of police officers to ensure a public function.

- While FWB is bound by the security laws of Country A, it will need to consult with its lawyers regarding its privacy obligations in Country A under foreign laws before it provides the names and addresses of any of its staff.

As exemplified in the case above, the legal restrictions to a negotiation process may be quite stringent. Many of these laws may also be used to draw undue advantages for the parties involved. It is therefore important for negotiators to:

- Know about the legal restrictions in force in the context. See which of these legal restrictions the government is actually enforcing (i.e., which ones are active red lines and which ones are more rhetorical);

- Identify which legal norms are potentially used to extract undue advantages (e.g., fees for a permit) and seek a clearance of these restrictions at a higher level;

- Avoid making legal arguments in a negotiation unless i) the laws are in force in the country; ii) these laws are recognized by the counterpart; and iii) these laws provide an incontestable advantage to the humanitarian organization; and

- Get the necessary legal advice to support such argument as the point of the negotiation is to seek the consent of the counterpart to operate and not force its compliance to given rules that favor the humanitarian operators.

As compared to other red lines, organizations have little control over the legal framework regulating their operations in the country. A number of these rules may impose restrictions that are in conflict with some of their values and policies and would prevent the negotiators from reaching an agreement that is both acceptable for the organization and legal in the jurisdiction. The organization should refrain from operating in this environment unless it is ready to change its red line or if the government agrees to exempt the organization from the rule. The fact that another organization is ready to comply with the demands at the cost of the legitimacy and legality of the arrangement is not a motive to violate one’s own rules.

Institutional Red Lines

Institutional norms constitute a significant pool of red lines of a humanitarian negotiation. The purpose of institutional norms is to maintain a coherent approach to the humanitarian mission of the organization and preserve the reputation of the organization within professional and donor circles. There are two categories of institutional red lines: a) Humanitarian principles, and b) Other institutional red lines.

Each of these institutional principles and norms entails specific red lines as part of the mandate of the negotiator or as elaborated in the course of dialogue with the mandator. It should be noted that, while legal red lines cannot be altered, institutional norms are under the control of the organization. There may be situations where the mandator may opt for or delegate the flexibility to the negotiation team to adapt the policies to the situation depending on the cost/benefit of the policy.

Humanitarian principles as institutional red lines

Humanitarian principles constitute an important source of institutional red lines, although their interpretations vary from one organization to the next. These principles involve the following:

Humanity

The object of the negotiation pertains to the provision of essential goods and services to preserve the life and dignity of affected individuals or populations. All objects of the negotiation falling within this definition are therefore allowed. Other objects (e.g., planting trees or paving a road) may fall outside the scope of humanitarian negotiation, depending on the context. The farther away the object of the negotiation from the principle of humanity, the more likely it will be affected by the institutional red line, depending on the organization’s interpretation of the principle of humanity. Some organizations may have a narrow vision of their humanitarian mission, limiting the objects of the negotiation to lifesaving assistance; others may include a larger series of life-enhancing and rights-promoting objectives (e.g., education programs, income generation, preservation of the environment, etc.) as an intrinsic part of their humanitarian vision. The varying nature of the vision implies that negotiators from different organizations may have distinct red lines pertaining to the purview of the negotiation—some are happy to entertain a large scope of options, others are reluctant to engage beyond lifesaving activities.

Neutrality

Humanitarian organizations generally agree that their programs in conflict zones should maintain a neutral stand in the eyes of the parties to the conflict, implying that they should not be perceived as taking sides regarding the matters at the core of the conflict. This institutional requirement does not imply that the negotiators should never take sides on any issue prevailing in the conflict. The negotiator should indeed take the side of vulnerable groups targeted by a party to the conflict, such as victims of forced displacement or children recruited by an armed group, as the mission of the humanitarian organization is to take on the interests of the civilians affected by armed conflict. This neutral perception is difficult to maintain in situations where one of the main goals of a party to the conflict is to take aim at challenges to the life and dignity of a segment of the population (e.g., discriminatory policies against the occupied population, ethnic cleansing, acts of genocide, etc.). In such case, the humanitarian negotiator striving to negotiate in favor of the victims of these policies may consequently appear as having lost his/her neutrality in the specific circumstances.

Impartiality

The principle of impartiality is one of the most valued aspects of humanitarian programming. It implies that essential assistance should be given to those most in need without any form of discrimination. It is also one of the most widely interpreted principles, considering the implications it may have on the frontlines, where access is often restricted by the parties to prevent the distribution of assistance to a specific group (e.g., to certain persons in besieged areas). Humanitarian organizations struggle to maintain an impartial approach as logistical, operational, and political considerations may affect the distribution of assistance to the population in need. Tactical considerations may also interfere in the setting up of priorities for distribution. Recurring questions include:

- Should the humanitarian organization deliver assistance only to those it is granted access to, at the expense of others most in need to whom access is prohibited?

- Should the organization refrain from assisting the former until it can secure access to the latter (e.g., those in a nearby besieged area)?

- Are there forms of discrimination (age, gender, ethnicity, religion, security status (e.g., for families of foreign fighters)) in the delivery of assistance that are more acceptable or objectionable than others in times of emergency or in intense political environments, or is the only discrimination allowed based on lesser needs? Where should the red line be?

The role of the mandator is to set the terms of impartiality in the eyes of the hierarchy of the organization, understanding that significant pressure will be imposed on the frontline negotiators. The mandator should remain engaged in reviewing and discussing the terms of agreements that impose restrictions on the access and delivery to the most vulnerable groups as humanitarian organizations may easily be instrumentalized by the counterparts and fall prey to the discriminatory policies they have been charged to balance off.

Independence

The principle of independence is among the most debated features of humanitarian programming. It entails the ability of organizations to draw policies and make decisions based on their own assessments, values, and norms, free from undue external influences, particularly external political actors. While policies of organizations are developed in an organic manner within the social environment of each entity, the principle of independence implies that internal policy and managerial decisions are made within transparent processes and primarily serve the mission of the organization.

Humanitarian negotiators should, however, remain skeptical about their own claim of independence, especially in the eyes of their counterparts. Humanitarian organizations exist and are allowed to operate thanks to a myriad of multifaceted dependencies within their respective social, professional, and political environments. Negotiators can always argue that their organization is trying its best to maintain the integrity of its activities and limit the influence of external actors. They should not appear oblivious to the actual dependencies of their organization. Even the core principles of humanitarian action should be understood as the product of the social and political culture of mid-1960s Cold War Europe, which carries over a number of political assumptions regarding, in part:

- The prominence of international norms over local rules and customs;

- The role of foreign humanitarian actors as carriers of these norms and edicts;

- The recognition of the central role of governments in addressing humanitarian needs;

- A reverence toward national sovereignty enshrined in positive international law;

- A suspicion about the role of communities and individuals in designing the humanitarian response;

- A narrow perspective on the geopolitics of international relations, including an aversion to the contribution of so-called for-profit corporate actors.

These assumptions are not innate to the mission of aid organizations but are integrated into the culture of many traditional humanitarian actors without much critical sense of the interests served by these assumptions. Rather than entering into this contentious debate, many professionals equate the independence of organizations with a narrow interpretation focusing on the financial dependency of their organization instead of on the origins of their policy culture over a number of assumed values, norms, and political visions. Other superficial notions of independence include the composition of the governance or the cultural, religious, and ethnic makeup of the staff, all potentially seen as evidence of undue influence.

The demonstration of independence of humanitarian negotiators pertains first and foremost to their national identity, whether being nationals of the country or foreign nationals, and, if the latter, from which country or countries.

As far as the independent standing of humanitarian negotiators, diversity in the negotiation team can be an important support to ensure that the notion of independence is recognized by the counterpart. In all cases, the independence of the organization should be judged in the eyes of the counterpart.

Other institutional policies as red lines

The organization may have adopted a series of policies regarding the multifaceted conduct of its operations. These policies are individual red lines framing the options for the negotiation team and informing the design of the scenarios. These may include, among other things:

- “Do no harm” policies that require due diligence in preventing harm toward the beneficiary population as a direct or indirect consequence of a humanitarian program;

- Duty of care regarding the well-being of staff;

- Professional procedures and protocols (e.g., requirements to employ only licensed physicians);

- Financial protocols and accountability mechanisms (e.g., requirements to document all expenses);

- Security protocols and measures (e.g., employment of guards for premises and residence); and,

- Rules pertaining to the prohibition of sexual harassment or abuses.

While some of these institutional red lines (e.g., do no harm or financial accountability requirements) are shared with most organizations operating in the same environment, others are often specific to each organization and to each context. Institutional red lines regarding professional behaviors tend to evolve over time, depending on the expectations of the donor, host government, beneficiaries, and the public.

To help situate institutional red lines in a context, one may consider the following example:

Example

The Governor of Country A is Eager to Ensure the Role and Control of His Government in the Distribution of Relief to Refugees

In the same case example as above, the head of the Office of the Governor informed FWB representatives that:

- The Governor insists on selecting the segment of the population most in need in the camp based on the information available to the government.

- Daily laborers who will assist in the delivery of assistance will need to be paid in cash through the Governor’s office. The office will see how to get receipts from the daily laborers for the payment, but it may take several weeks before the receipts will be handed over to FWB.

- Security guards will be equipped with sticks and will use them on the camp population to ensure that people will stay in line as they are being counted by FWB staff.

- The Governor intends to make a speech to camp leaders at the beginning of the distribution of FWB food rations to praise the efforts of his government toward the welfare of refugees.

- Ultimately, the Governor will host a private party at this residence where “girls” from the camp will entertain guests.

FWB representatives who have been briefed on the institutional policies of the organization have to respond to these requests. Yet, in view of the urgency of the lifesaving assistance, the negotiation team is considering its options, in consultation with the mandator, to ensure that the assistance will be delivered to the camp in time.

- They will not allow selection of the recipients of assistance by the Governor unless FWB can also select its own recipients.

- Daily laborers will need to be paid in cash directly by FWB, in the presence of a staff member of the Governor’s office.

- Considering that guards in the camp are always equipped with sticks, FWB will probably need to close its eyes to the use of such method to keep order during the delivery of assistance. It will look for ways to limit disorderly behavior during the counting of population. FWB will actively seek alternative models of crowd control.

- They may decide to allow the Governor to make a speech but will take measures to disassociate the delivery of assistance from the government considering the fact that most of the camp dwellers are from families of rebels.

- In no way will FWB staff participate in a private party where women and girls from the camp will be subject to sexual harassment or prostitution.

Professional Red Lines

There may be other professional restrictions that may not be part of the institutional policies of the organization but represent important red lines to maintain the professional standing of the negotiator and of the organization. These restrictions often pertain to the professional status of the organization and the conduct of its staff within their respective professional community (e.g., physicians, engineers, accountants, nutritionists, security personnel, etc.). Professional norms are directed toward demonstrating the rigor of the professional staff and the delivery of services. They may include:

- Expected methods of assessing needs and delivery of aid;

- Expected methods of dealing with beneficiaries;

- Other expected professional behaviors (e.g., attire, attitude, etc.).

There may be cases where the counterpart may entangle humanitarian negotiators in paradoxical situations in terms of professional behavior as a way to weaken their standing at the negotiation table. For example (including, but not limited to):

- Imposing disruptive emotional behaviors on the negotiation team at the meeting (anger, shouting, emotional debrief, etc.);

- Inciting excessive drinking of alcohol prior to or at the negotiation table;

- Requiring to meet in the middle of the night for no particular reason;

- Requiring the use of inadequate tools or methods (e.g., conduct of an assessment using lists in local language without interpretation);

- Prohibiting contact with the population in the camp.

The professional standing of an organization may prohibit some of these restrictions even if there are no specific institutional policies. These expectations are part of the professional character of the staff hired by the organization and can be context-specific as well. There may be situations where the local rules of decency or politeness may contravene the professional standing of the organization in another context (e.g., chewing khat, eating using one’s right hand, etc.). Local rules and customs govern the behavior of the parties at the negotiation table as long as these rules do not undermine the capacity and dignity of the negotiators.

A negotiator should remain aware that a sudden lack of respect of the counterpart for the professional standing of the negotiation team may be a sign of a significant degradation of the situation.

A party intending to jeopardize a negotiation will likely communicate its intent early through gestures of professional disrespect that have to be read in their context (e.g., unexplained cancellation of a meeting, extensive wait before a meeting, weapons in the meeting room, unexplained silence during the meeting, absence of eye contact, refusal to shake hands, aggressive tone, shuffling of people at the table, etc.). These may be signs of an impending conflict in the negotiation process or growing threat toward the negotiation team. The same expectations apply to the humanitarian negotiator’s behavior, which can easily be misread. The professional standing, attire, and appropriate behavior in the context are important means to ensure that the negotiation process remains on track at all times despite the prevalence of difficult issues, tensions, or unstable interlocutors.

Moral or Ethical Red Lines

A final source of red lines could be based on personal moral or ethical dimensions without necessarily having an institutional policy or professional standing. These restrictions focus on moral standing and have a personal dimension that makes them difficult to manage or be objective about, being linked at times to personal behaviors as well as religious or moral beliefs. Growing discomfort is a signal of getting too close to some of these red lines. These may include:

- A female negotiator may be asked to join the male counterpart for an informal discussion in his private quarters;

- A negotiator may be asked to join a religious ceremony or to profess a belief different from his/her own;

- A negotiator may be asked to take part in a cultural event that goes against his/her belief (e.g., eating meat for a strict vegetarian) during the negotiation process.

There are numerous situations that can become major sources of discomfort which may or may not be intended by the counterpart or the humanitarian organization.

The fact that negotiation processes are often about finding the right compromises may create the perception that humanitarian negotiators may be ready to be complicit with the illegal or immoral purpose and methods of the counterpart. For example:

Example

On the Detention of Children Among Adults

The International Monitoring Network (IMN), an international NGO mandated to monitor the treatment of detainees, is visiting a local prison in a conflict zone. During one of these visits, IMN monitors observe that a number of children are detained with the adult population in a clear breach of national and international standards protecting children. Several of them showed signs of abuse. In view of the absence of alternative places of detention and resources, all stakeholders in the prison request the IMN monitors to ignore the particular situation of children even though they could lose access to the location and put these children at even more risk.

Such a situation should be a source of major concern for the humanitarian negotiator as it may contravene a number of red lines, including ethical ones. Without judging the case prematurely, the negotiator is bound to discuss this ethical issue with his/her team and the mandator, who should be the one making the call on the cost/benefit of a denunciation of the abuses to national prison authorities vs. allowing the children to stay with the adults in view of the risk of losing access to the location. The context and circumstances are paramount to evaluate the possible ways to address the protection of the children. First and foremost is the question of whether children will be better protected in an alternative location in view of other threats they may face.

While everyone has moral imperatives, frontline negotiators should be aware that morality and ethics are in essence cultural norms and may require some tact in finding an appropriate solution to differences. Yet, the moral standing of the negotiators is as important as the professional or institutional standing of the organization. Frontline negotiators should therefore avoid ambiguities about their moral character and reputation, as well as their own moral imperatives under the local customs.

Flexibility Regarding Red Lines and Institutional Policies

Red lines are part of the mandate of the negotiator. These cannot be changed or revised without the agreement of the mandator. There may be circumstances where red lines are not as absolute as they may appear. For example:

- While payment for the release of hostages is a definite red line for many organizations, the granting of safe evacuation or other advantages to the hostage takers is understood at times as an acceptable compromise under specific circumstances.

- While the diversion of assistance by armed groups is a definite red line for many organizations, the distribution of food to the families of militia members may be allowed under specific circumstances.

- While the military escort of humanitarian convoys is a definite red line for many organizations, extreme needs and sustained insecurity from criminal gangs may dictate the limited use of armed escorts on specific segments.

In other words, while red lines are definite limitations of the mandate of the negotiator, they may be adapted in view of exceptional circumstances of the situation in terms of a cost/benefit analysis of these policies. There may be situations where the red lines should be adapted by the mandator so as to ensure the humanitarian character of the mission and the objectives of the organization. These decisions have major consequences on the modus operandi and reputation of the organization as well as setting expectations for future negotiations and operations. They should be made at the appropriate level of the hierarchy. In all cases, the negotiator is, in principle, not allowed to make decisions on the determination of the red lines as they affect the core of his/her mandate, which is not under his/her control.

Application of the Tool

This segment presents a set of practical steps to review the applicable institutional policies and inform the identification of the red lines as part of the design scenario for the negotiation process.

It will also examine the case brought up in the previous segment regarding the retention of staff to exemplify the steps to be followed in this process. The case is presented here as a point of reference.

Example

Health for All’s Surgical Team Detained in a Labor Dispute

Nine staff members of Health for All (HfA), an international health NGO, have been prohibited by tribesmen from leaving their residence in District A for almost a week following a disagreement between HfA and the guards of the local HfA hospital. This dispute follows HfA’s plans to close the hospital due to decreasing war surgery needs in the region. The guards, who belong to an important tribe in the region, claim that the hospital should remain open and their compensation be paid as there are still considerable emergency health needs in the region. The guards, supported by tribal representatives, further argue that they put their lives at risk for several years to maintain the access of patients and staff to the hospital during an especially violent conflict. Some of the guards even lost their life in this process and others sustained long-term disabilities. Families of the guards wounded or killed during the conflict further request long-term monetary compensation for the loss of income before HfA pulls out of District A.

For now, the hospital is barely operational, with several emergency needs left unattended. The tribal leaders have agreed to meet with HfA representatives to look for a solution. The government has refrained from intervening in what they see as a private labor dispute. The army and police have only a limited presence and control over the situation in District A and would not intervene without the support of the tribal chiefs.

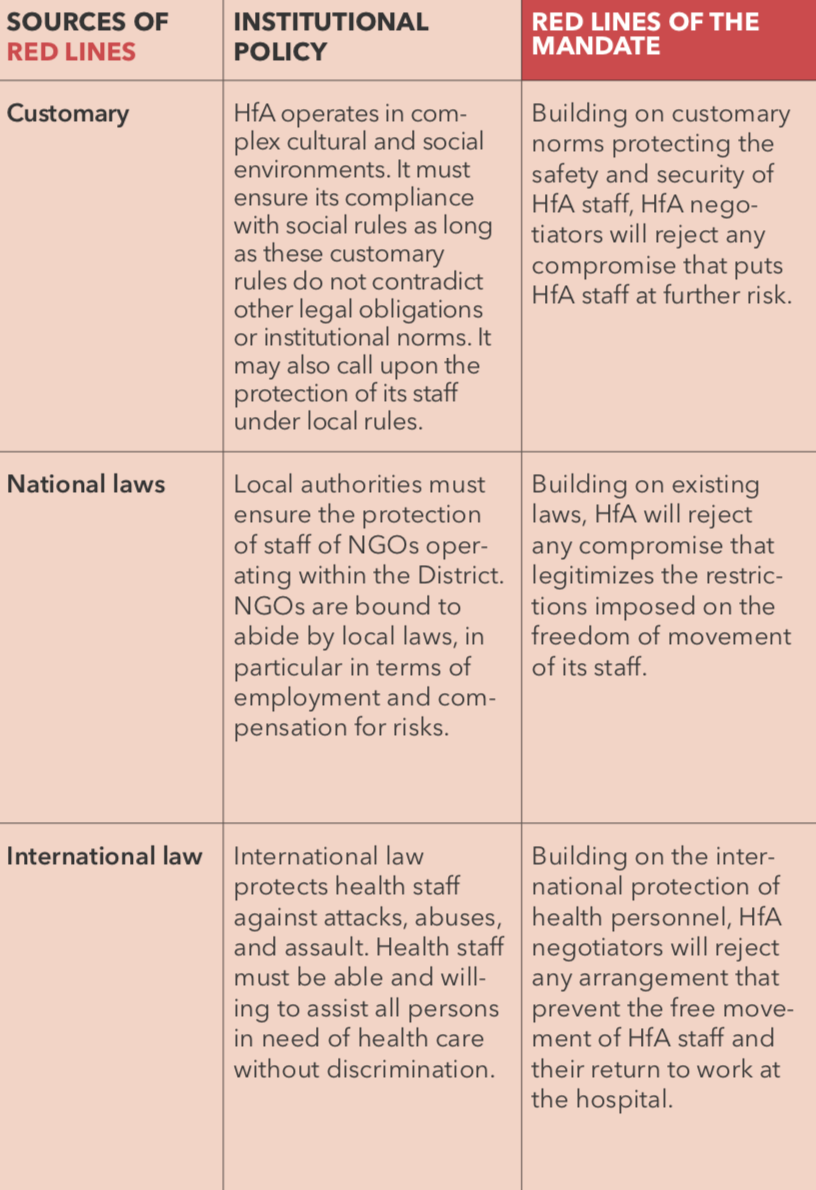

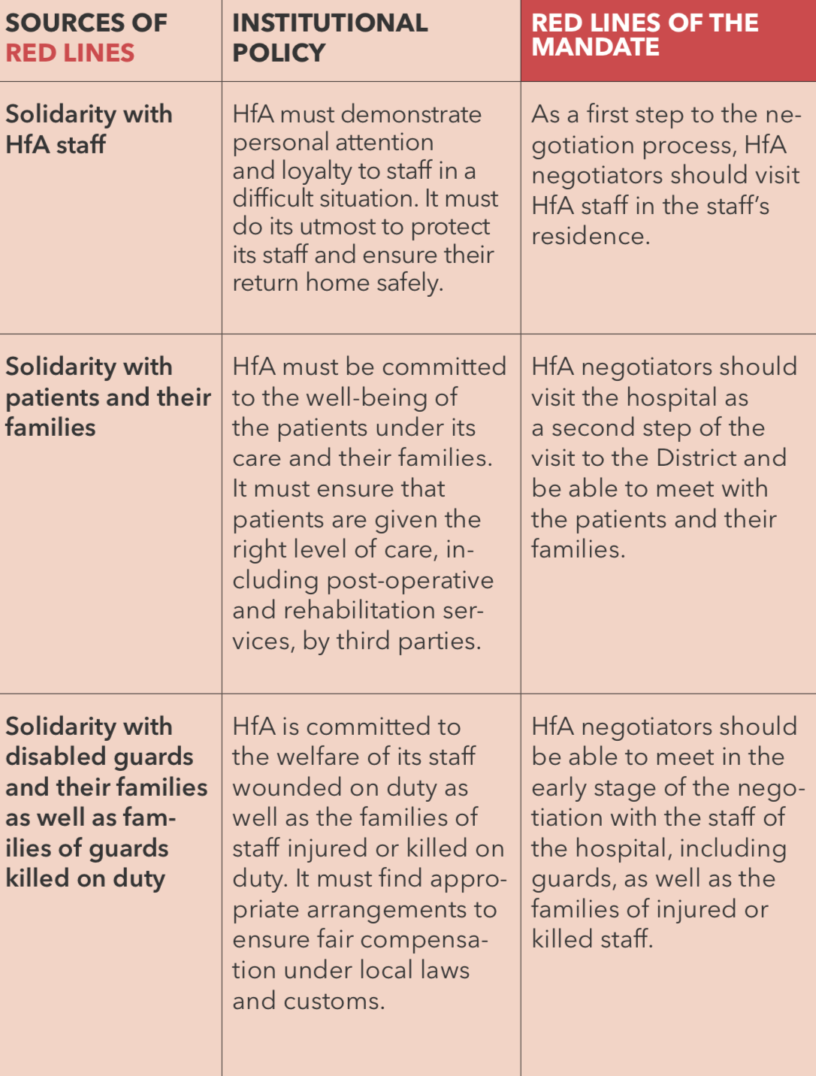

Step 1: Identify the current red lines by sources of institutional policies and extract the appropriate red lines for the negotiator.

A number of legal, institutional, professional, and ethical red lines are at play in this context. Each red line represents a policy of the humanitarian organization, Health for All.

Legal Red Lines

Institutional Red Lines

Professional Red Lines

Moral Red Lines

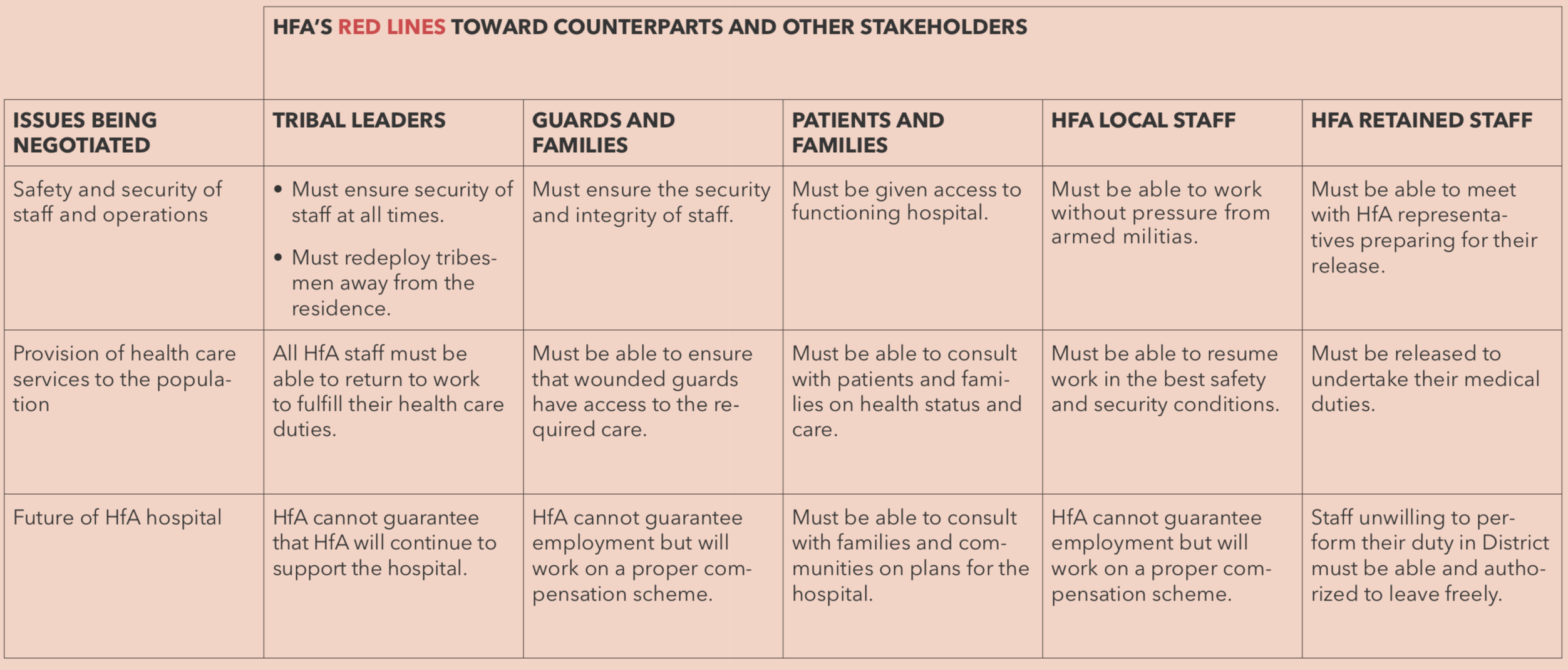

Step 2: Define the red lines for the negotiation with the main counterparts and stakeholders

Using the tables above, create a new table that summarizes and simplifies the red lines for each of the main objectives of the negotiation and for each of the counterparts and stakeholders. The new table will be useful not so much as a regulatory framework, but as the starting point of conversation with the negotiator, the mandator, and the negotiation team. The cumulative table should therefore be regularly revisited and reapproved by the mandator.

As a summary of the applicable policies, the red lines of the mandate are as follows:

Cumulated Red Lines Informing the HfA Negotiator’s Mandate

Red lines are more “tools” than “rules” of humanitarian negotiation.

Designing and implementing red lines

Contrary to the strategic objectives of the negotiation which deserve to be written down and articulated as part of the iceberg of the humanitarian organization, red lines are more a source of discussion and reflections between the negotiator, the negotiation team, and the mandator. Red lines need to be put into place in the original mandate by the mandator. Yet, their impact on a negotiation should materialize through regular conversations and feedback among these actors. Their dialogue is to help the negotiator stay in line within the legal, professional, and ethical standards of the organization. The red lines further allow the negotiators to maintain a certain level of neutrality between the counterparts and their organization. The role of the negotiators is to intercede between the two icebergs and look for a compromise. Red lines determine an acceptable scope of possibilities for the organization, not for the negotiator per se. Hence, the mandator should always be responsible for deciding on the red lines and never give this role to the negotiator. If the humanitarian negotiator were seen to have authority to control or bend the red lines, the counterparts could put pressure on the negotiator. It would become difficult, if not intractable to maintain a minimum standard without being responsible for the breakdown of the negotiation.

Concluding Remarks and Key Lessons of This Tool

This module provides a reflection on red lines and their role in guiding and managing a negotiation process. The mandator is responsible for setting up red lines and revising them regularly via an ongoing dialogue with the negotiator and the negotiation team. Red lines have a number of sources, from community rules to national laws, professional standards, and ethical norms. These norms may come into conflict. It is critical that the negotiator engages with his/her team to review and discuss normative tensions as they are at the core of the humanitarian negotiation process. Ultimately, red lines are an essential part of a negotiation. Their implementation should be as cogent as the operations that will result from the negotiation.