The CCHN Field Manual on Frontline Humanitarian Negotiation proposes a comprehensive method to conduct humanitarian negotiation in a structured and customised manner. It offers a step-by-step pathway to plan and implement negotiation processes based on a set of practical tools designed to:

- Analyse complex negotiation environments;

- Assess the position, interests, and motives of all the parties involved;

- Build networks and leverage influence;

- Define the terms of a negotiation mandate and clarify negotiation objectives;

- Set limits (red lines) to these negotiations;

- Identify specific objectives and design scenarios; and

- Enter transactions in an effective manner to ensure proper implementation.

These tools are further articulated in a separate Negotiator’s Notebook, Workbook, and Digital Platform linking core knowledge on humanitarian negotiation to ongoing negotiation practices in field operations. The ultimate objective of the CCHN Field Manual is to facilitate the sharing of field experiences and reflections on humanitarian negotiation practices among the members of the CCHN community of practice. By offering a simple experiential model, the goal of the CCHN Field Manual and its related platforms is to become an integral part of the professional conversations among humanitarian practitioners engaged in negotiation processes with civil authorities, military forces, non-state armed groups, affected communities, and other agencies and NGOs in the deployment of lifesaving assistance and protection programs.

The CCHN Field Manual should serve as complementary reading to the existing literature on humanitarian principles and action. It assumes a core knowledge of humanitarian values and professional norms as well as a degree of proficiency in managing humanitarian programs. It will be most useful to practitioners who already benefit from some years of operational experience in conflict environments. The CCHN Field Manual is not meant to define or promote specific objectives of humanitarian negotiation but to present systematic tools to improve negotiation practices based on the experience and wisdom of this growing community of practice.

Defining Humanitarian Negotiation

Humanitarian negotiation is defined as a set of interactions between humanitarian organisations and parties to an armed conflict, as well as other relevant actors, aimed at establishing and maintaining the presence of these organisations in conflict environments, ensuring access to vulnerable groups, and facilitating the delivery of assistance and protection activities. Negotiations may involve both state and non-state actors. They include a relational component focused on building trust with the counterparts over time and a transactional component focused on determining and agreeing on the specific terms and logistics of humanitarian operations.

Many readers will find the tools and observations in the CCHN Field Manual quite familiar, as the tools and methods are for the most part drawn from actual practices. The content of the first version of the CCHN Field Manual was initially informed by the interviews of over 120 field practitioners who have shared their experiences and lessons learned in recent years. The second version has further benefitted from the inputs of over 1000 experienced field practitioners who have taken part in the peer exchange programs organised by the CCHN and its partners. Humanitarian negotiation is more than a technique that one can learn from books and training workshops. It is also more than a personal skill or intuition based on the individual experiences of isolated colleagues. By facilitating the dissemination of experience across time and various locations, the CCHN emphasises its belief that best practices in humanitarian negotiation should be the product of a joint endeavour among hundreds of frontline negotiators across contexts and agencies. Through the sharing of negotiation practices and reflections among peers, involving comparing tactics, analysing judgments, and reviewing errors, the CCHN hopes to bolster the collective wisdom of this emerging professional community.

The CCHN encourages humanitarian organisations to create a safe and positive environment in which negotiation experience can be shared and learned from among peers. Humanitarian professionals are invited to join such discussions in the course of CCHN regional and context-specific peer workshops as well as other CCHN peer exchange activities for field practitioners across organisations. The larger the community of practice, the deeper the negotiation experience and reflections of its members will be. As the CCHN continues to expand the circle of participants through its peer activities, it is expected that the experiential material contained in the CCHN Field Manual and related digital platforms will contribute to improving the capacity of humanitarian organisations to seek access to populations in need in increasingly complex environments.

Sharing views and experiences on the challenges of negotiating on the frontlines

Frontline humanitarian negotiators are known to conduct highly contextual, personal, and confidential negotiation processes in some of the most remote and challenging environments. While being part of global operations, most frontline negotiators tend to work in isolation from each other and enjoy only limited access to critical information and discussions on negotiation practices in their own situation or across contexts. In recent years, humanitarian negotiators have increasingly recognised commonalities in their practices and the challenges they face in complex environments. The growing interdependence of humanitarian actors on the ground implies a greater need for sharing of experience and peer learning to improve humanitarian outcomes of frontline negotiations.

Origins of the CCHN Field Manual

Paradoxically, limited attention has been devoted so far to strengthening the negotiation capabilities of humanitarian organisations. While the demand for such skills and methods is constantly growing, there are few instances of training programs dedicated to humanitarian negotiation in field operations. Humanitarian organisations have often been uneasy about discussing their negotiation practices, considering the personal, contextual, and confidential character of relationships with counterparts. For many, negotiation with parties to armed conflict has been, and is still, often perceived as part of political interplays among states and other powerful actors taking place outside the humanitarian space and away from the recognised humanitarian principles. Field practitioners will recognise that negotiation has become a major part of their activities but remain uncomfortable in discussing their experience without a proper humanitarian language and framework. The few instances of literature on humanitarian negotiation in the 20th century are often composed of over-glorified stories of engagements with little to no critical reflections on the tactical dilemmas of these interventions and their political environments. At the risk of downplaying the contributions of leading negotiators and the role of frontline humanitarian organisations, there has been little effort in recent decades to collect actual data on negotiation practices and systematise humanitarian negotiation tools and methods.

It is only since the late 1990s that reflections on humanitarian negotiation, mediation, and diplomacy have introduced new domains of policy inquiry. This expansion of observations of frontline engagements parallels the growing numbers of humanitarian actors entering this domain of activities since the end of the Cold War. This amplification is also the product of the increased blending of operational agendas from the traditional humanitarian action to preserve life and dignity to more development-oriented programming, conflict management, and mediation activities. The first professional guidelines on humanitarian negotiations have been published in the early 2000s by the Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue, OCHA and Conflict Dynamics International (see insert). As part of its institutional strategy calling for more evidence-based reflections on its operational practices, the ICRC undertook a first review of its negotiation practices starting in 2013 under the Humanitarian Negotiation Exchange (HNx) program, which further aimed at fostering a community of practice among ICRC negotiators. This effort prompted other organisations to join and engage in similar reviews.

Engaging in Critical Reflections on the Common Dilemmas of Humanitarian Negotiation

A paradox persists around the role that negotiators play in humanitarian action. On the one hand, humanitarian organisations have limited leeway to negotiate as their action is rooted in non-negotiable humanitarian principles—humanity, impartiality, neutrality, and independence. On the other hand, field operations rely on the ability of humanitarian professionals to seek and maintain access to affected populations by finding the proper arrangements to manage the expectations of the counterparts, while protecting the security of staff and cooperating with local actors. As a result, humanitarian actors find themselves caught between the need to respect humanitarian norms and principles and their role to find the right balance of interests with their counterparts to fulfil their mission and have an impact.

It is in this context that the leadership of the five members of the Strategic Partners on Humanitarian Negotiation (ICRC, WFP, UNHCR, MSF and HD) created in late 2016 the Centre of Competence on Humanitarian Negotiation (CCHN), inspired by an ICRC internal platform favouring the exchange of negotiation experiences among field practitioners. In the Strategic Partners’ view, most of the knowledge and experience required to effectively undertake the challenges of frontline negotiation are already present in field operations, spread among experienced humanitarian professionals operating on the frontlines. The best way to build the capability of agencies to negotiate in these demanding circumstances is to facilitate the capture, analysis, and sharing of negotiation experiences among frontline negotiators and across agencies and contexts. The mission of the CCHN focuses specifically on creating a safe space among humanitarian negotiators to share their practices and to enable critical reflections on negotiation strategies and tactics in complex environments. These exchanges consequently nurture the elaboration of the CCHN Field Manual tailored to the needs and demands of field practitioners.

Training and Policy Guidance in Humanitarian Negotiation

Starting in the late 1990s, research and policy centres invested in the development of the first guidance on humanitarian negotiation. Deborah Mancini-Griffoli and André Picot wrote a first Humanitarian Negotiation Handbook in 2004, published by the HD Centre, which recognised the need to plan and prepare a humanitarian negotiation process. In 2006, under the auspices of OCHA, Gerard McHugh and Manuel Bessler produced a Manual for Practitioners on Humanitarian Negotiation with Armed Groups to develop policy guidance on addressing the dilemmas of principled negotiations, later revised in 2011 by Conflict Dynamics International (CDI) and the Swiss Department of Foreign Affairs. More recently, training programs have been developed by CDI, the Clingendael Institute, CERAH, and the Danish Red Cross/the Norwegian Refugee Council, among others, introducing core knowledge, tools, and skills on humanitarian negotiation and community mediation. The peer workshops of the CCHN are the latest iteration of this process, opening a safe space to exchange negotiation experience and reflect on challenges and dilemmas of humanitarian negotiation.

On the Role of the CCHN Community

Since the launch of the activities of the CCHN in 2016, this reflection has involved several hundred humanitarian professionals from various agencies and local organizations across field operations. As of October 2019, over a thousand field practitioners have taken part in CCHN peer-to-peer activities. These activities are based on the conscious efforts of participants to engage in informal exchanges on personal negotiation experiences as a central means to learn common approaches to complex negotiations and to assist others.

As members of the CCHN community, field practitioners can further take part in specialized sessions on themes selected by participants in the peer workshops. These sessions may, in turn, trigger the creation of “peer circles” of 10-15 members hosted by the CCHN who meet regularly to share information and review strategies of ongoing negotiation processes. Field research conducted by the CCHN and its academic partners on selected challenges and dilemmas of frontline negotiations further inform specialized sessions and peer circles as required by the members of the CCHN community. Finally, participants in the peer activities can opt to become CCHN Facilitators by following a dedicated training organized by the CCHN. CCHN Facilitators orient peers and manage exchanges as well as guide the development of CCHN tools and methods. As the community progresses, the CCHN will be able to identify and review emerging challenges and dilemmas of humanitarian negotiation and develop pathways to deal with them.

At this early stage, members of the CCHN community have started conversations to define the core competences of frontline humanitarian negotiators in terms of knowledge, attitudes, and skills underpinning the necessary capabilities to undertake humanitarian negotiation. This “competence chart” is designed to help members of the CCHN community, as well as their agencies, in focusing their attention on key features to invest in as they are considering ways to strengthen negotiation capabilities across humanitarian operations (see ANNEX 1). These conversations have also led toward a greater awareness among community members about their commitment to colleagues on the frontlines as well as a sense of due diligence to agencies and other stakeholders in the development of this critical professional domain.

On the Planning of a Negotiation Process

The CCHN Field Manual builds on the assumption that one needs to ascertain a common framework of analysis and vocabulary to be able to compare negotiation experiences across time, contexts and issues in a useful manner. While negotiation experiences are inherently personal and contextual in nature, they also present recurring dilemmas and challenges from which one can learn and instigate more effective tools and methods. These common features also support the establishment of a shared professional space for the planning of negotiation processes, exchanges of experience, and professional reflections.

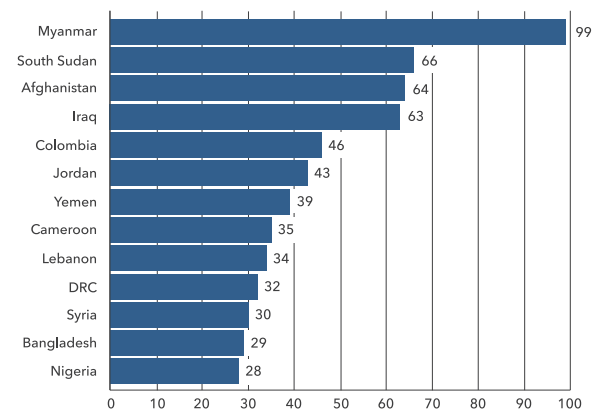

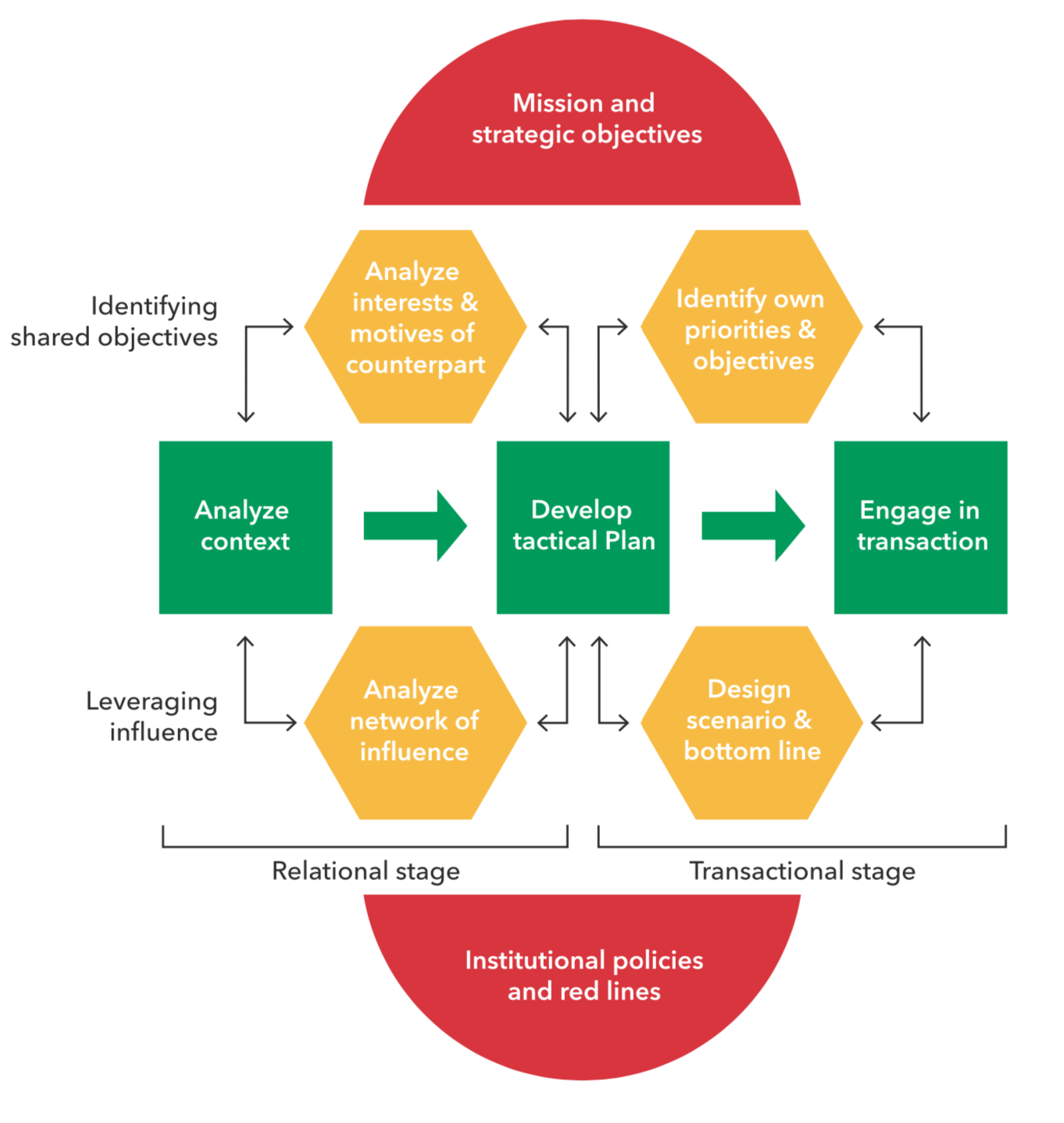

From 2016 onward, the CCHN has been gathering information on the negotiation practices of several hundred humanitarian professionals covering their experience, tactics, and strategies. This empirical analysis was guided by the early reflections on humanitarian negotiation practices conducted by 24 ICRC frontline negotiators in Naivasha, Kenya, in November 2014. The Naivasha gathering organized by the ICRC’s Humanitarian Exchange Platform – a precursor of the CCHN, produced a first model of a generic humanitarian negotiation process in terms of planning steps, consultations, and engagements with the counterparts and their stakeholders based on the negotiation experience of the ICRC participants. The original Naivasha Grid was presented as an ICRC planning tool for frontline humanitarian negotiation at the first Annual Meeting of Frontline Humanitarian Negotiators in October 2016. The Naivasha Grid framework was further developed and adapted to a multi-agency setting by the CCHN in the following years. It became both an analytical tool to observe and review humanitarian negotiation processes across agencies and contexts and a map to plan the successive tasks, roles, and responsibilities between the frontline negotiator, his/her support team, and the mandator responsible for framing the negotiation exercise in a given mandate (see Figure 3).

The Naivasha Grid confirms the leading role of the frontline negotiator in the negotiation process defined along the Green Pathway. This role is supported in an intermittent manner by the negotiation team which the frontline negotiator is part of, along the Yellow Pathway, implying a critical dialogue between frontline negotiators and field colleagues to consider tactical options based on the interests and motives of counterparts, the specific objectives of the negotiation, the design of scenarios, and the mapping of the networks of influence. The whole negotiation process is framed by the mandator, along the Red Pathway, in terms of strategic objectives and red lines informed by institutional policies. These policies and objectives are assigned by the mandator to the negotiator, generally through the line management within the organization.

While the Naivasha Grid provides a set of logical pathways drawn from recent practices, it focuses primarily on the specific steps of a negotiation process. Several important aspects of humanitarian operations that surround and inform the negotiation process, including the assessment of needs, the design of programs, internal deliberations, and negotiation with the mandator, have been omitted from the Grid. The implementation of a final agreement is also not covered by the Naivasha Grid. While these aspects are central to humanitarian programming and action, they are not understood as key to the practice of a frontline negotiator in relation with his/her counterparts, which is the focus of the CCHN Field Manual.

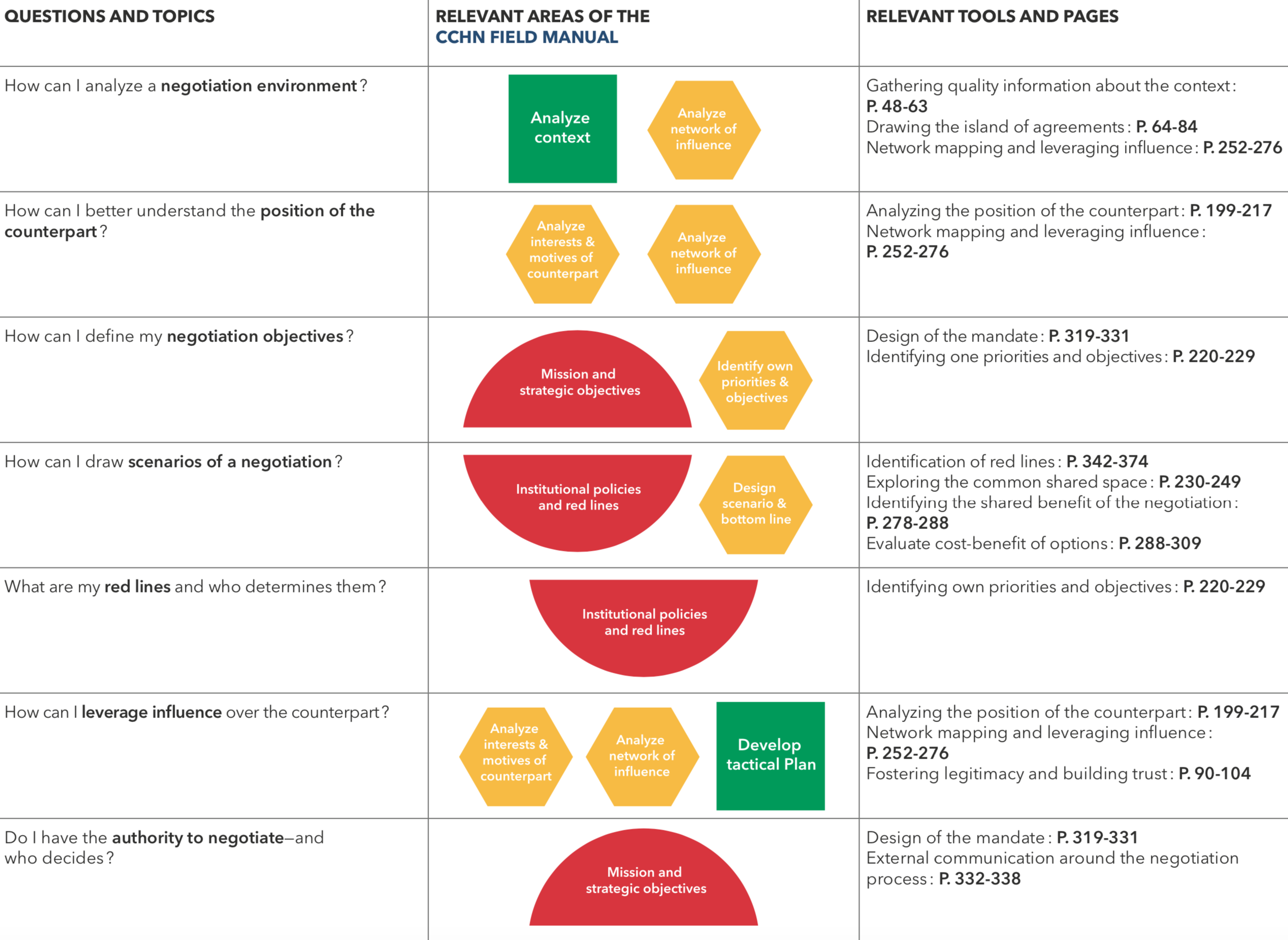

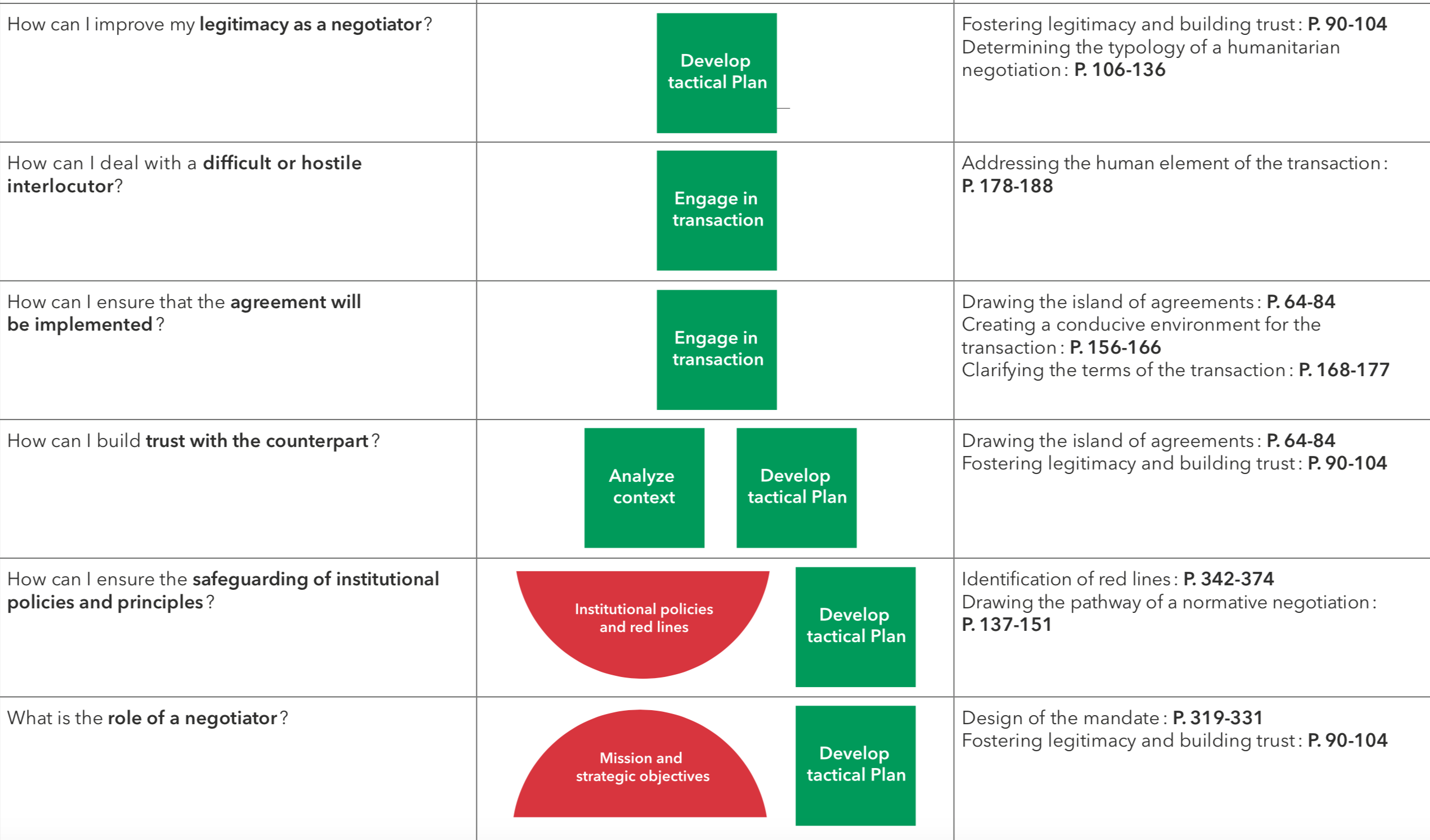

Quick Guide on How to Use the CCHN Field Manual

The CCHN Field Manual presents humanitarian negotiation as a linear planning and deliberation process. It provides specific tools and reflections on every step of the process as well as a pattern of distribution of roles and responsibilities. It is important to mention that these steps and roles should not be taken in isolation. A manager or field operator can be engaged at various stages of concurrent negotiation processes in the same context where he/she may act alternatively as mandator, team member, or frontline negotiator, depending on the specific object of the negotiation and level of the counterpart. The Naivasha Grid encourages interactions between these steps and roles with the understanding that their actual distribution may evolve from one engagement to the next. A junior manager should therefore, for example, learn to lead a negotiation process on the frontline as well as play a support role as a team member and eventually mandate a negotiation process to a staff member under his/her supervision. The capabilities of an organisation to negotiate on the frontlines entail a collective endeavor where the three distinct roles are properly assigned and recognised contributing equally to the success of the operation.

The CCHN Field Manual follows the distribution of roles and responsibilities documented in the Naivasha Grid by the CCHN Community in recent years. Hence:

-

- The Green section of the CCHN Field Manual focuses on the specific tasks of the frontline negotiator managing the relationship and leading the transactional discussion with the counterpart(s);

- The Yellow section focuses on the support role of the negotiator’s team in accompanying the frontline negotiator in the planning and critical review of the negotiation process; and

- The Red section focuses on the role and responsibilities of the mandator as part of the institutional hierarchy of the organisation defining the terms of the mandate of the frontline negotiator, including its limits (red lines), and reviewing the results of the negotiation.

Readers will find an arrangement of practical tools for each role within each of the sections, accompanied by real-life examples. These tools have further been compiled in the workbook related to the CCHN Field Manual (available on the CCHN website) where practitioners can test their knowledge and apply the tools and methods to reflect on ongoing negotiations. The workbook should be not only a learning tool, but also a useful compilation of templates to use in a negotiation process. It is expected that negotiation practitioners will refer to the most relevant areas of the CCHN Field Manual in support of the planning of ongoing negotiation processes.

The following table assists readers in identifying the most relevant segments of the CCHN Field Manual based on the topics or questions that bring them to the Manual.