Olivier Eyenga, who trained as a teacher, has a rich humanitarian background. He works for the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) in Niamey, Niger. He is head of the civil-military coordination unit. Previously, worked in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Chad, Niger and Haiti, where he was present just hours after the earthquake. Olivier is used to being sent into the field as soon as a crisis occurs.

He began his humanitarian career in his home country, the DRC, as a humanitarian affairs officer in 2000. From the very start of his career, Olivier was keen to make humanitarian aid accessible in decentralised areas by opening humanitarian antennae. More than 20 years later, he continues this mission by offering negotiation workshops based on the CCHN methodology in hard-to-reach places.

He joined the CCHN community in 2021 after attending a workshop on humanitarian negotiation, which focused on the regions of Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso. Since then, he has also become a facilitator and has enabled many humanitarian professionals to attend negotiation workshops.

Olivier likes to teach, share knowledge and help others revisit the way they work. For him, it’s important to stop and take the time to think about how we do things. He shares why in this interview.

Hello and welcome Olivier! Tell us how you became a humanitarian.

When I started setting up humanitarian offices or community coordination units in remote areas of the DRC, I had to work with military leaders and non-state armed groups, which opened my eyes to the world of humanitarian negotiation. It was mostly on a case-by-case basis, and I didn’t have any negotiation tools or methodology to structure these negotiations.

I was reassigned to Niamey in 2020, where humanitarian operations are conducted in areas where there are also military operations. It’s important to be able to talk and interact with the military and the national authorities to get access to people in need. Today, I’m still negotiating, but I know how to prepare and structure my negotiations. That’s why it’s important to take the time to revisit the way we work.

Participants in a community-led peer workshop by Olivier Eyenga in Kalemie, DRC learning how structure a humanitarian negotiation.

Why was it important for you to equip yourself for negotiations?

This was important to me because I wanted to go beyond simple contact with the authorities, non-state actors and other stakeholders. That’s where I discovered the Centre of Competence for Humanitarian Negotiation.

When you receive a new mission order, sometimes you don’t even see your unit leader. The next day, you have to get on a plane to go to the field for the mission. You get there, but you don’t necessarily have the address book for what’s waiting for you. You want to carry out your mission order, but you arrive in a place where there are already red lines that must not be crossed. For example, you don’t know who may or may not be approached or who is under embargo.

I found myself in a dilemma between my humanitarian obligations, where I had to access an area, and my safety. So I reported to my superiors, but they asked me for results without telling me how to achieve them.

On one occasion, I had to influence a regional governor in order to succeed in my humanitarian mission. I had to understand who all the people around him were before I could talk to him. If I had taken the CCHN peer workshop earlier to revisit the way I work, I would have known that I absolutely had to identify the right target group to make a difference to the results of my mission. Context analysis is essential. It’s important to map out your situation, to understand what level of negotiation I’m at and what different attitudes I might have with my various counterparts.

Equipping ourselves for negotiations helps us to structure them and to better understand the environment into which we have been dropped with no information other than we have to deliver results.

What motivated you to facilitate workshops on humanitarian negotiation?

It’s about sharing my experience with others. I was lucky enough to do the peer workshop on humanitarian negotiation and then the training of facilitators straight afterwards. The presentation of the tools really opened my eyes.

I’ve had to manage crises in the DRC, Haiti and Chad. With hindsight, I know that it’s better to anticipate. The more we have a critical mass of people who know the CCHN tools, the better things will go in the field. That’s why I’ve facilitated several workshops myself.

After completing the training, I was very interested in being able to share this knowledge with the younger humanitarian community around me. There are a lot of humanitarians who are deployed in emergency situations, but who have no basic training.

With the support of the CCHN, I was able to share the tools with other colleagues who also wanted to be trained in humanitarian negotiation. I used the case studies in the CCHN manual, contextualising them. I had plenty of scope to draw on my own experiences.

Colleagues gave positive feedback and I continued to offer workshops to support the humanitarian community. At one point, I delivered workshops in four different sites with difficult travel, all within three weeks, with the help of other facilitator colleagues.

I did some in the DRC in Bukavu, Kalemie, Goma and Bunia. I’ve also done some in Niger, in Tillabéri, Lam and Tahoua.

In my office, I’m the in-house CCHN, that’s what they call me here.

In short, the more we make negotiation tools accessible to the general public so they can revisit the way they work in their own time, the more we contextualise them and the more people use them, the better it helps the humanitarian world.

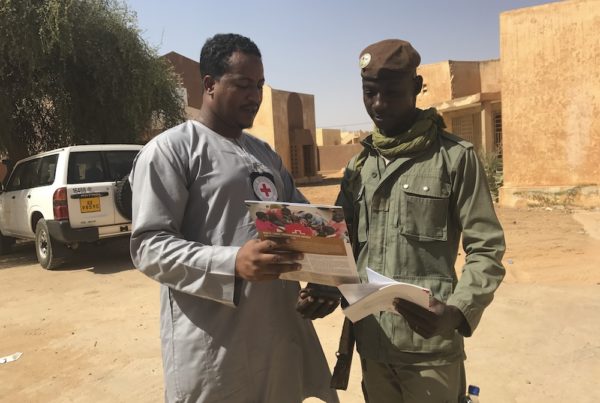

A negotiation simulation during a community-led peer workshop by Olivier Eyenga in Ouallam, Niger.

What would you say to people who say they don't have time to do a workshop on humanitarian negotiation?

I would tell them that this is a big mistake. Personal development and capacity building are elements that need to be integrated into everything to do with team performance. Even if you’re dealing with one emergency after another at work, you have to be able to stop. You need to ask yourself whether the way you’re handling these emergencies is effective. It’s important to stop.

The working world is changing, particularly with new technologies. It is evolving with innovations, research, studies… It would be a mistake to not take the time to revisit the way we work.

If people don’t take the time to learn how to integrate these tools and methodologies, sooner or later they’ll have to do it at their own expense, in a reactive way, but perhaps in another form.

When we are faced with a counterpart, we often believe that the counterpart does not prepare. But this is not true. They do prepare. They ask themselves why this person wants to meet with them, what they want to talk about, and so on. So teams also need to prepare.

These days, talking to the wrong person can cause your own programme to suffer. We’re in an environment where one person can do something that undermines the work of others over several years.

It’s better to “waste this time” attending a workshop than to continue working as usual with people whose actions could compromise the programmes.

If there’s one message we need to get across, it’s that we need to learn from the experience of others and remember that these tools are for the humanitarian community to improve the way they work.